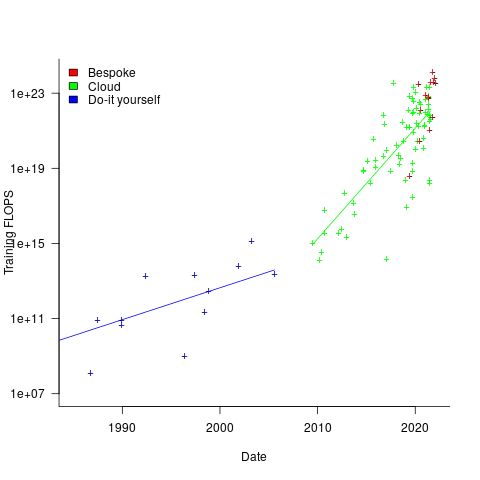

Growth in FLOPs used to train ML models

AI (a.k.a. machine learning) is a compute intensive activity, with the performance of trained models being dependent on the quantity of compute used to train the model.

Given the ongoing history of continually increasing compute power, what is the maximum compute power that might be available to train ML models in the coming years?

How might the compute resources used to train an ML model be measured?

One obvious answer is to specify the computers used and the numbers of days used they were occupied training the model. The problem with this approach is that the differences between the computers used can be substantial. How is compute power measured in other domains?

Supercomputers are ranked using FLOPS (floating-point operations per second), or GigFLOPS or PetaFLOPS ( ). The Top500 list gives values for

). The Top500 list gives values for  (based on benchmark performance, i.e., LINNPACK) and

(based on benchmark performance, i.e., LINNPACK) and  (what the hardware is theoretically capable of, which is sometimes more than twice

(what the hardware is theoretically capable of, which is sometimes more than twice  ).

).

A ballpark approach to measuring the FLOPs consumed by an application is to estimate the FLOPS consumed by the computers involved and multiply by the number of seconds each computer was involved in training. The huge assumption made with this calculation is that the application actually consumes all the FLOPS that the hardware is capable of supplying. In some cases this appears to be the metric used to estimate the compute resources used to train an ML model. Some published papers just list a FLOPs value, while others list the number of GPUs used (e.g., 2,128).

A few papers attempt a more refined approach. For instance, the paper describing the GPT-3 models derives its FLOPs values from quantities such as the number of parameters in each model and number of training tokens used. Presumably, the research group built a calibration model that provided the information needed to estimate FLOPS in this way.

How does one get to be able to use PetaFLOPS of compute to train a model (training the GPT-3 175B model consumed 3,640 PetaFLOP days, or around a few days on a top 8 supercomputer)?

Pay what it costs. Money buys cloud compute or bespoke supercomputers (which are more cost-effective for large scale tasks, if you have around £100million to spend plus £10million or so for the annual electricity bill). While the amount paid to train a model might have lots of practical value (e.g., can I afford to train such a model), researchers might not be keen to let everybody know how much they spent. For instance, if a research team have a deal with a major cloud provider to soak up any unused capacity, those involved probably have no interest in calculating compute cost.

How has the compute power used to train ML models increased over time? A recent paper includes data on the training of 493 models, of which 129 include estimated FLOPs, and 106 contain date and model parameter data. The data comes from published papers, and there are many thousands of papers that train ML models. The authors used various notability criteria to select papers, and my take on the selection is that it represents the high-end of compute resources used over time (which is what I’m interested in). While they did a great job of extracting data, there is no real analysis (apart from fitting equations).

The plot below shows the FLOPs training budget used/claimed/estimated for ML models described in papers published on given dates; lines are fitted regression models, and the colors are explained below (code+data):

My interpretation of the data is based on the economics of accessing compute resources. I see three periods of development:

- do-it yourself (18 data points): During this period most model builders only had access to a university computer, desktop machines, or a compute cluster they had self-built,

- cloud (74 data points): Huge on demand compute resources are now just a credit card away. Researchers no longer have to wait for congested university computers to become available, or build their own systems.

AWS launched in 2006, and the above plot shows a distinct increase in compute resources around 2008.

- bespoke (14 data points): if the ML training budget is large enough, it becomes cost-effective to build a bespoke system, e.g., a supercomputer. As well as being more cost-effective, a bespoke system can also be specifically designed to handle the characteristics of the kinds of applications run.

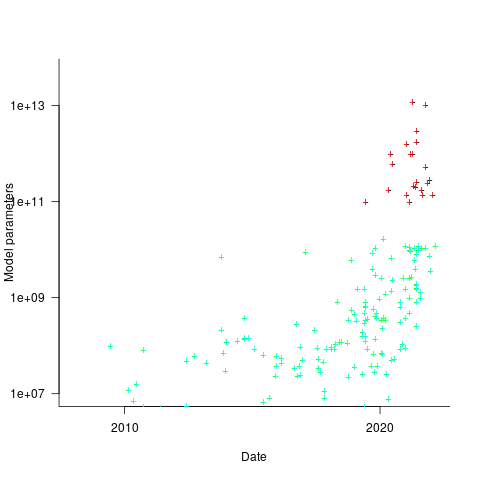

How might models trained using a bespoke system be distinguished from those trained using cloud compute? The plot below shows the number of parameters in each trained model, over time, and there is a distinct gap between

and

and  parameters, which I assume is the result of bespoke systems having the memory capacity to handle more parameters (code+data):

parameters, which I assume is the result of bespoke systems having the memory capacity to handle more parameters (code+data):

The rise in FLOPs growth rate during the Cloud period comes from several sources: 1) the exponential decline in the prices charged by providers delivers researchers an exponentially increasing compute for the same price, 2) researchers obtaining larger grants to work on what is considered to be an important topic, 3) researchers doing deals with providers to make use of excess capacity.

The rate of growth of Cloud usage is capped by the cost of building a bespoke system. The future growth of Cloud training FLOPs will be constrained by the rate at which the prices charged for a FLOP decreases (grants are unlikely to continually increase substantially).

The rate of growth of the Top500 list is probably a good indicator of the rate of growth of bespoke system performance (and this does appear to be slowing down). Perhaps specialist ML training chips will provide performance that exceeds that of the GPU chips currently being used.

The maximum compute that can be used by an application is set by the reliability of the hardware and the percentage of resources used to recover from hard errors that occur during a calculation. Supercomputer users have been facing the possibility of hitting the wall of maximum compute for over a decade. ML training is still a minnow in the supercomputer world, where calculations run for months, rather than a few days.

Cost-effectiveness decision for fixing a known coding mistake

If a mistake is spotted in the source code of a shipping software system, is it more cost-effective to fix the mistake, or to wait for a customer to report a fault whose root cause turns out to be that particular coding mistake?

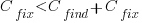

The naive answer is don’t wait for a customer fault report, based on the following simplistic argument:  .

.

where:  is the cost of fixing the mistake in the code (including testing etc), and

is the cost of fixing the mistake in the code (including testing etc), and  is the cost of finding the mistake in the code based on a customer fault report (i.e., the sum on the right is the total cost of fixing a fault reported by a customer).

is the cost of finding the mistake in the code based on a customer fault report (i.e., the sum on the right is the total cost of fixing a fault reported by a customer).

If the mistake is spotted in the code for ‘free’, then  , e.g., a developer reading the code for another reason, or flagged by a static analysis tool.

, e.g., a developer reading the code for another reason, or flagged by a static analysis tool.

This answer is naive because it fails to take into account the possibility that the code containing the mistake is deleted/modified before any customers experience a fault caused by the mistake; let  be the likelihood that the coding mistake ceases to exist in the next unit of time.

be the likelihood that the coding mistake ceases to exist in the next unit of time.

The more often the software is used, the more likely a fault experience based on the coding mistake occurs; let  be the likelihood that a fault is reported in the next time unit.

be the likelihood that a fault is reported in the next time unit.

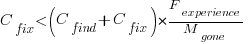

A more realistic analysis takes into account both the likelihood of the coding mistake disappearing and a corresponding fault being reported, modifying the relationship to:

Software systems are eventually retired from service; the likelihood that the software is maintained during the next unit of time,  , is slightly less than one.

, is slightly less than one.

Giving the relationship:

which simplifies to:

What is the likely range of values for the ratio:  ?

?

I have no find/fix cost data, although detailed total time is available, i.e., find+fix time (with time probably being a good proxy for cost). My personal experience of find often taking a lot longer than fix probably suffers from survival of memorable cases; I can think of cases where the opposite was true.

The two values in the ratio  are likely to change as a system evolves, e.g., high code turnover during early releases that slows as the system matures. The value of

are likely to change as a system evolves, e.g., high code turnover during early releases that slows as the system matures. The value of  should decrease over time, but increase with a large influx of new users.

should decrease over time, but increase with a large influx of new users.

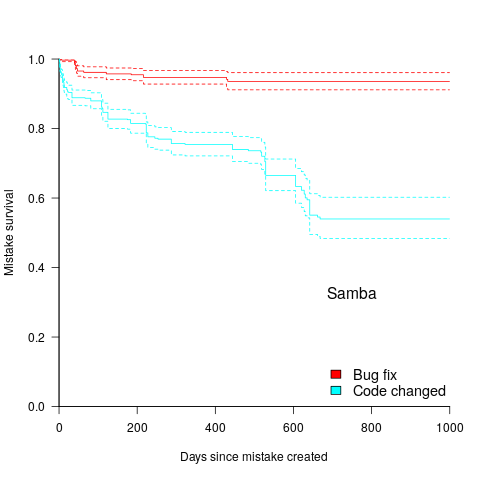

A study by Penta, Cerulo and Aversano investigated the lifetime of coding mistakes (detected by several tools), tracking them over three years from creation to possible removal (either fixed because of a fault report, or simply a change to the code).

Of the 2,388 coding mistakes detected in code developed over 3-years, 41 were removed as reported faults and 416 disappeared through changes to the code:

The plot below shows the survival curve for memory related coding mistakes detected in Samba, based on reported faults (red) and all other changes to the code (blue/green, code+data):

Coding mistakes are obviously being removed much more rapidly due to changes to the source, compared to customer fault reports.

For it to be cost-effective to fix coding mistakes in Samba, flagged by the tools used in this study ( is essentially one), requires:

is essentially one), requires:  .

.

Meeting this requirement does not look that implausible to me, but obviously data is needed.

Software engineering research is a field of dots

Software engineering research is a field of dots; people are fully focused on publishing papers about their chosen tiny little subject.

Where are the books joining the dots into even a vague outline?

Several software researchers have told me that writing books is not a worthwhile investment of their time, i.e., the number of citations they are likely to attract makes writing papers the only cost-effective medium (books containing an edited collection of papers continue to be published).

Butterfly collecting has become the method of study for many researchers. The butterflies in question often being Github repos that are collected together, based on some ‘interestingness’ metric, and then compared and contrasted in a conference paper.

The dots being collected are influenced by the problems that granting agencies consider to be important topics to fund (picking a research problem that will attract funding is a major consideration for any researcher). Fake research is one consequence of incentivizing people to use particular techniques in their research.

Whatever you think the aims of research in software engineering might be, funding the random collecting of dots does not seem like an effective strategy.

Perhaps it is just a matter of waiting for the field to grow up. Evidence-based software engineering research is still a teenager, and the novelty of butterfly collecting has yet to wear off.

My study of particular kinds of dots did not reveal many higher level patterns, although a number of folk theories were shown to be unfounded.

Estimation experiments: specification wording is mostly irrelevant

Existing software effort estimation datasets provide information about estimates made within particular development environments and with particular aims. Experiments provide a mechanism for obtaining information about estimates made under conditions of the experimenters choice, at least in theory.

Writing the code is sometimes the least time-consuming part of implementing a requirement. At hackathons, my default estimate for almost any non-trivial requirement is a couple of hours, because my implementation strategy is to find the relevant library or package and write some glue code around it. In a heavily bureaucratic organization, the coding time might be a rounding error in the time taken up by meeting, documentation and testing; so a couple of months would be considered normal.

If we concentrate on the time taken to implement the requirements in code, then estimation time and implementation time will depend on prior experience. I know that I can implement a lexer for a programming language in half-a-day, because I have done it so many times before; other people take a lot longer because they have not had the amount of practice I have had on this one task. I’m sure there are lots of tasks that would take me many days, but there is somebody who can implement them in half-a-day (because they have had lots of practice).

Given the possibility of a large variation in actual implementation times, large variations in estimates should not be surprising. Does the possibility of large variability in subject responses mean that estimation experiments have little value?

I think that estimation experiments can provide interesting information, as long as we drop the pretence that the answers given by subjects have any causal connection to the wording that appears in the task specifications they are asked to estimate.

If we assume that none of the subjects is sufficiently expert in any of the experimental tasks specified to realistically give a plausible answer, then answers must be driven by non-specification issues, e.g., the answer the client wants to hear, a value that is defensible, a round number.

A study by Lucas Gren and Richard Berntsson Svensson asked subjects to estimate the total implementation time of a list of tasks. I usually ignore software engineering experiments that use student subjects (this study eventually included professional developers), but treating the experiment as one involving social processes, rather than technical software know-how, makes subject software experience a lot less relevant.

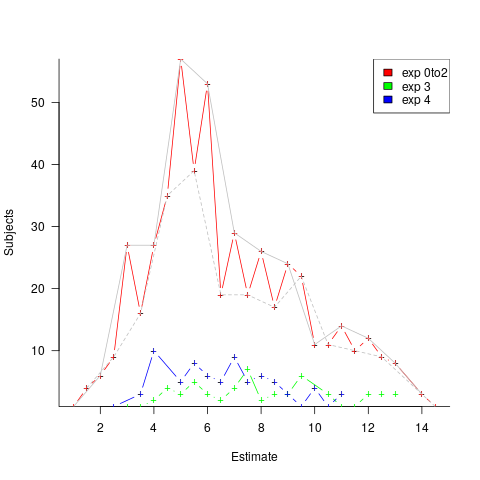

Assume, dear reader, that you took part in this experiment, saw a list of requirements that sounded plausible, and were then asked to estimate implementation time in weeks. What estimate would you give? I would have thrown my hands up in frustration and might have answered 0.1 weeks (i.e., a few hours). I expected the most common answer to be 4 weeks (the number of weeks in a month), but it turned out to be 5 (a very ‘attractive’ round number), for student subjects (code+data).

The professional subjects appeared to be from large organizations, who I assume are used to implementations including plenty of bureaucratic stuff, as well as coding. The task specification did not include enough detailed information to create an accurate estimate, so subjects either assumed their own work environment or played along with the fresh-faced, keen experimenter (sorry Lucas). The professionals showed greater agreement in that the range of value given was not as wide as students, but it had a more uniform distribution (with maximums, rather than peaks, at 4 and 7); see below. I suspect that answers at the high end were from managers and designers with minimal coding experience.

What did the experimenters choose weeks as the unit of estimation? Perhaps they thought this expressed a reasonable implementation time (it probably is if it’s not possible to use somebody else’s library/package). I think that they could have chosen day units and gotten essentially the same results (at least for student subjects). If they had chosen hours as the estimation unit, the spread of answers would have been wider, and I’m not sure whether to bet on 7 (hours in a working day) or 10 being the most common choice.

Fitting a regression model to the student data shows estimates increasing by 0.4 weeks per year of degree progression. I was initially baffled by this, and then I realized that more experienced students expect to be given tougher problems to solve, i.e., this increase is based on self-image (code+data).

The stated hypothesis investigated by the study involved none of the above. Rather, the intent was to measure the impact of obsolete requirements on estimates. Subjects were randomly divided into three groups, with each seeing and estimating one specification. One specification contained four tasks (A), one contained five tasks (B), and one contained the same tasks as (A) plus an additional task followed by the sentence: “Please note that R5 should NOT be implemented” (C).

A regression model shows that for students and professions the estimate for (A) is about 1-2 weeks lower than (B), while (A) estimates are 3-5 weeks lower than (C) estimated.

What are subjects to make of an experimental situation where the specification includes a task that they are explicitly told to ignore?

How would you react? My first thought was that the ignore R5 sentence was itself ignored, either accidentally or on purpose. But my main thought is that Relevance theory is a complicated subject, and we are a very long way away from applying it to estimation experiments containing supposedly redundant information.

The plot below shows the number of subjects making a given estimate, in days; exp0to2 were student subjects (dashed line joins estimate that include a half-hour value, solid line whole hour), exp3 MSc students, and exp4 professional developers (code+data):

I hope that the authors of this study run more experiments, ideally working on the assumption that there is no connection between specification and estimate (apart from trivial examples).

semgrep: the future of static analysis tools

When searching for a pattern that might be present in source code contained in multiple files, what is the best tool to use?

The obvious answer is grep, and grep is great for character-based pattern searches. But patterns that are token based, or include information on language semantics, fall outside grep‘s model of pattern recognition (which does not stop people trying to cobble something together, perhaps with the help of complicated sed scripts).

Those searching source code written in C have the luxury of being able to use Coccinelle, an industrial strength C language aware pattern matching tool. It is widely used by the Linux kernel maintainers and people researching complicated source code patterns.

Over the 15+ years that Coccinelle has been available, there has been a lot of talk about supporting other languages, but nothing ever materialized.

About six months ago, I noticed semgrep and thought it interesting enough to add to my list of tool bookmarks. Then, a few days ago, I read a brief blog post that was interesting enough for me to check out other posts at that site, and this one by Yoann Padioleau really caught my attention. Yoann worked on Coccinelle, and we had an interesting email exchange some 13-years ago, when I was analyzing if-statement usage, and had subsequently worked on various static analysis tools, and was now working on semgrep. Most static analysis tools are created by somebody spending a year or so working on the implementation, making all the usual mistakes, before abandoning it to go off and do other things. High quality tools come from people with experience, who have invested lots of time learning their trade.

The documentation contains lots of examples, and working on the assumption that things would be a lot like using Coccinelle, I jumped straight in.

The pattern I choose to search for, using semgrep, involved counting the number of clauses contained in Python if-statement conditionals, e.g., the condition in: if a==1 and b==2: contains two clauses (i.e., a==1, b==2). My interest in this usage comes from ideas about if-statement nesting depth and clause complexity. The intended use case of semgrep is security researchers checking for vulnerabilities in code, but I’m sure those developing it are happy for source code researchers to use it.

As always, I first tried building the source on the Github repo, (note: the Makefile expects a git clone install, not an unzipped directory), but got fed up with having to incrementally discover and install lots of dependencies (like Coccinelle, the code is written on OCaml {93k+ lines} and Python {13k+ lines}). I joined the unwashed masses and used pip install.

The pattern rules have a yaml structure, specifying the rule name, language(s), message to output when a match is found, and the pattern to search for.

After sorting out various finger problems, writing C rather than Python, and misunderstanding the semgrep output (some of which feels like internal developer output, rather than tool user developer output), I had a set of working patterns.

The following two patterns match if-statements containing a single clause (if.subexpr-1), and two clauses (if.subexpr-2). The option commutative_boolop is set to true to allow the matching process to treat Python’s or/and as commutative, which they are not, but it reduces the number of rules that need to be written to handle all the cases when ordering of these operators is not relevant (rules+test).

rules: - id: if.subexpr-1 languages: [python] message: if-cond1 patterns: - pattern: | if $COND1: # we found an if statement $BODY - pattern-not: | if $COND2 or $COND3: # must not contain more than one condition $BODY - pattern-not: | if $COND2 and $COND3: $BODY severity: INFO - id: if.subexpr-2 languages: [python] options: commutative_boolop: true # Reduce combinatorial explosion of rules message: if-cond2 pattern-either: - patterns: - pattern: | if $COND1 or $COND2: # if statement containing two conditions $BODY - pattern-not: | if $COND3 or $COND4 or $COND5: # must not contain more than two conditions $BODY - pattern-not: | if $COND3 or $COND4 and $COND5: $BODY - patterns: - pattern: | if $COND1 and $COND2: $BODY - pattern-not: | if $COND3 and $COND4 and $COND5: $BODY - pattern-not: | if $COND3 and $COND4 or $COND5: $BODY severity: INFO |

The rules would be simpler if it were possible for a pattern to not be applied to code that earlier matched another pattern (in my example, one containing more clauses). This functionality is supported by Coccinelle, and I’m sure it will eventually appear in semgrep.

This tool has lots of rough edges, and is still rapidly evolving, I’m using version 0.82, released four days ago. What’s exciting is the support for multiple languages (ten are listed, with experimental support for twelve more, and three in beta). Roughly what happens is that source code is mapped to an abstract syntax tree that is common to all supported languages, which is then pattern matched. Supporting a new language involves writing code to perform the mapping to this common AST.

It’s not too difficult to map different languages to a common AST that contains just tokens, e.g., identifiers and their spelling, literals and their value, and keywords. Many languages use the same operator precedence and associativity as C, plus their own extras, and they tend to share the same kinds of statements; however, declarations can be very diverse, which makes life difficult for supporting a generic AST.

An awful lot of useful things can be done with a tool that is aware of expression/statement syntax and matches at the token level. More refined semantic information (e.g., a variable’s type) can be added in later versions. The extent to which an investment is made to support the various subtleties of a particular language will depend on its economic importance to those involved in supporting semgrep (Return to Corp is a VC backed company).

Outside of a few languages that have established tools doing deep semantic analysis (i.e., C and C++), semgrep has the potential to become the go-to static analysis tool for source code. It will benefit from the network effects of contributions from lots of people each working in one or more languages, taking their semgrep skills and rules from one project to another (with source code language ceasing to be a major issue). Developers using niche languages with poor or no static analysis tool support will add semgrep support for their language because it will be the lowest cost path to accessing an industrial strength tool.

How are the VC backers going to make money from funding the semgrep team? The traditional financial exit for static analysis companies is selling to a much larger company. Why would a large company buy them, when they could just fork the code (other company sales have involved closed-source tools)? Perhaps those involved think they can make money by selling services (assuming semgrep becomes the go-to tool). I have a terrible track record for making business predictions, so I will stick to the technical stuff.

Finding patterns in construction project drawing creation dates

I took part in Projecting Success‘s 13th hackathon last Thursday and Friday, at CodeNode (host to many weekend hackathons and meetups); around 200 people turned up for the first day. Team Designing-Success included Imogen, Ryan, Dillan, Mo, Zeshan (all building construction domain experts) and yours truly (a data analysis monkey who knows nothing about construction).

One of the challenges came with lots of real multi-million pound building construction project data (two csv files containing 60K+ rows and one containing 15K+ rows), provided by SISK. The data contained information on project construction drawings and RFIs (request for information) from 97 projects.

The construction industry is years ahead of the software industry in terms of collecting data, in that lots of companies actually collect data (for some, accumulate might be a better description) rather than not collecting/accumulating data. While they have data, they don’t seem to be making good use of it (so I am told).

Nearly all the discussions I have had with domain experts about the patterns found in their data have been iterative, brief email exchanges, sometimes running over many months. In this hack, everybody involved is sitting around the same table for two days, i.e., the conversation is happening in real-time and there is a cut-off time for delivery of results.

I got the impression that my fellow team-mates were new to this kind of data analysis, which is my usual experience when discussing patterns recently found in data. My standard approach is to start highlighting visual patterns present in the data (e.g., plot foo against bar), and hope that somebody says “That’s interesting” or suggests potentially more interesting items to plot.

After several dead-end iterations (i.e., plots that failed to invoke a “that’s interesting” response), drawings created per day against project duration (as a percentage of known duration) turned out to be of great interest to the domain experts.

Building construction uses a waterfall process; all the drawings (i.e., a kind of detailed requirements) are supposed to be created at the beginning of the project.

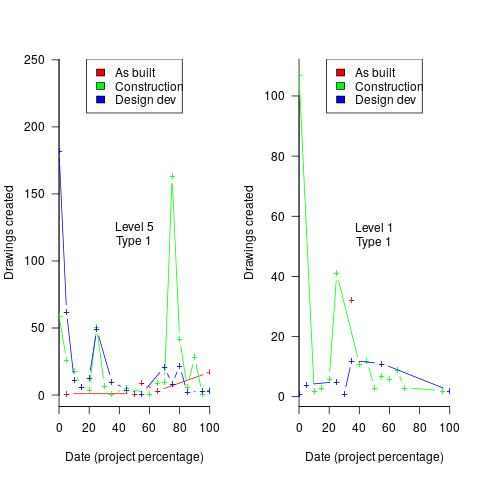

Hmm, many individual project drawing plots were showing quite a few drawings being created close to the end of the project. How could this be? It turns out that there are lots of different reasons for creating a drawing (74 reasons in the data), and that it is to be expected that some kinds of drawings are likely to be created late in the day, e.g., specific landscaping details. The 74 reasons were mapped to three drawing categories (As built, Construction, and Design Development), then project drawings were recounted and plotted in three colors (see below).

The domain experts (i.e., everybody except me) enjoyed themselves interpreting these plots. I nodded sagely, and occasionally blew my cover by asking about an acronym that everybody in the construction obviously knew.

The project meta-data includes a measure of project performance (a value between one and five, derived from profitability and other confidential values) and type of business contract (a value between one and four). The data from the 97 projects was combined by performance and contract to give 20 aggregated plots. The evolution of the number of drawings created per day might vary by contract, and the hypothesis was that projects at different performance levels would exhibit undesirable patterns in the evolution of the number of drawings created.

The plots below contain patterns in the quantity of drawings created by percentage of project completion, that are: (left) considered a good project for contract type 1 (level 5 are best performing projects), and (right) considered a bad project for contract type 1 (level 1 is the worst performing project). Contact the domain experts for details (code+data):

The path to the above plot is a common one: discover an interesting pattern in data, notice that something does not look right, use domain knowledge to refine the data analysis (e.g., kinds of drawing or contract), rinse and repeat.

My particular interest is using data to understand software engineering processes. How do these patterns in construction drawings compare with patterns in the software project equivalents, e.g., detailed requirements?

I am not aware of any detailed public data on requirements produced using a waterfall process. So the answer is, I don’t know; but the rationales I heard for the various kinds of drawings sound as-if they would have equivalents in the software requirements world.

What about the other data provided by the challenge sponsor?

I plotted various quantities for the RFI data, but there wasn’t any “that’s interesting” response from the domain experts. Perhaps the genius behind the plot ideas will be recognized later, or perhaps one of the domain experts will suddenly realize what patterns should be present in RFI data on high performance projects (nobody is allowed to consider the possibility that the data has no practical use). It can take time for the consequences of data analysis to sink in, or for new ideas to surface, which is why I am happy for analysis conversations to stretch out over time. Our presentation deck included some RFI plots because there was RFI data in the challenge.

What is the software equivalent of construction RFIs? Perhaps issues in a tracking system, or Jira tickets? I did not think to talk more about RFIs with the domain experts.

How did team Designing-Success do?

In most hackathons, the teams that stay the course present at the end of the hack. For these ProjectHacks, submission deadline is the following day; the judging is all done later, electronically, based on the submitted slide deck and video presentation. The end of this hack was something of an anti-climax.

Did team Designing-Success discover anything of practical use?

I think that finding patterns in the drawing data converted the domain experts from a theoretical to a practical understanding that it was possible to extract interesting patterns from construction data. They each said that they planned to attend the next hack (in about four months), and I suggested that they try to bring some of their own data.

Can these drawing creation patterns be used to help monitor project performance, as it progressed? The domain experts thought so. I suspect that the users of these patterns will be those not closely associated with a project (those close to a project are usually well aware of that fact that things are not going well).

Moore’s law was a socially constructed project

Moore’s law was a socially constructed project that depended on the coordinated actions of many independent companies and groups of individuals to last for as long it did.

All products evolve, but what was it about Moore’s law that enabled microelectronics to evolve so much faster and for longer than most other products?

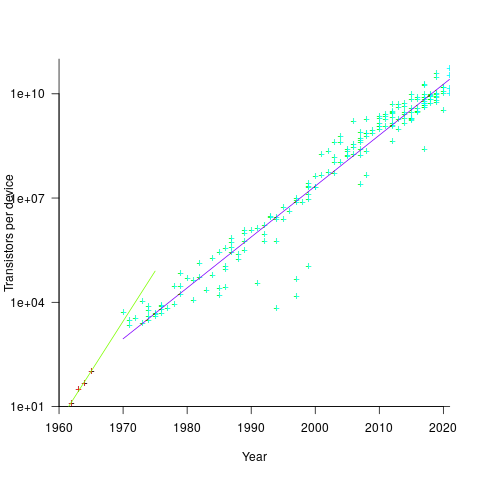

Moore’s observation, made in 1965 based on four data points, was that the number of components contained in a fabricated silicon device doubles every year. The paper didn’t make this claim in words, but a line fitted to four yearly data points (starting in 1962) suggested this behavior continuing into the mid-1970s. The introduction of IBM’s Personal Computer, in 1981 containing Intel’s 8088 processor, led to interested parties coming together to create a hugely profitable ecosystem that depended on the continuance of Moore’s law.

The plot below shows Moore’s four points (red) and fitted regression model (green line). In practice, since 1970, fitting a regression model (purple line) to the number of transistors in various microprocessors (blue/green, data from Wikipedia), finds that the number of transistors doubled every two years (code+data):

In the early days, designing a device was mostly a manual operation; that is, the circuit design and logic design down to the transistor level were hand-drawn. This meant that creating a device containing twice as many transistors required twice as many engineers. At some point the doubling process either becomes uneconomic or it takes forever to get anything done because of the coordination effort.

The problem of needing an exponentially-growing number of engineers was solved by creating electronic design automation tools (EDA), starting in the 1980s, with successive generations of tools handling ever higher levels of abstraction, and human designers focusing on the upper levels.

The use of EDA provides a benefit to manufacturers (who can design differentiated products) and to customers (e.g., products containing more functionality).

If EDA had not solved the problem of exponential growth in engineers, Moore’s law would have maxed-out in the early 1980s, with around 150K transistors per device. However, this would not have stopped the ongoing shrinking of transistors; two economic factors independently incentivize the creation of ever smaller transistors.

When wafer fabrication technology improvements make it possible to double the number of transistors on a silicon wafer, then around twice as many devices can be produced (assuming unchanged number of transistors per device, and other technical details). The wafer fabrication cost is greater (second row in table below), but a lot less than twice as much, so the manufacturing cost per device is much lower (third row in table).

The doubling of transistors primarily provides a manufacturer benefit.

The following table gives estimates for various chip foundry economic factors, in dollars (taken from the report: AI Chips: What They Are and Why They Matter). Node, expressed in nanometers, used to directly correspond to the length of a particular feature created during the fabrication process; these days it does not correspond to the size of any specific feature and is essentially just a name applied to a particular generation of chips.

Node (nm) 90 65 40 28 20 16/12 10 7 5 Foundry sale price per wafer 1,650 1,937 2,274 2,891 3,677 3,984 5,992 9,346 16,988 Foundry sale price per chip 2,433 1,428 713 453 399 331 274 233 238 Mass production year 2004 2006 2009 2011 2014 2015 2017 2018 2020 Quarter Q4 Q4 Q1 Q4 Q3 Q3 Q2 Q3 Q1 Capital investment per wafer 4,649 5,456 6,404 8,144 10,356 11,220 13,169 14,267 16,746 processed per year Capital consumed per wafer 411 483 567 721 917 993 1,494 2,330 4,235 processed in 2020 Other costs and markup 1,293 1,454 1,707 2,171 2,760 2,990 4,498 7,016 12,753 per wafer |

The second economic factor incentivizing the creation of smaller transistors is Dennard scaling, a rarely heard technical term named after the first author of a 1974 paper showing that transistor power consumption scaled with area (for very small transistors). Halving the area occupied by a transistor, halves the power consumed, at the same frequency.

The maximum clock-frequency of a microprocessor is limited by the amount of heat it can dissipate; the heat produced is proportional to the power consumed, which is approximately proportional to the clock-frequency. Instead of a device having smaller transistors consume less power, they could consume the same power at double the frequency.

Dennard scaling primarily provides a customer benefit.

Figuring out how to further shrink the size of transistors requires an investment in research, followed by designing/(building or purchasing) new equipment. Why would a company, who had invested in researching and building their current manufacturing capability, be willing to invest in making it obsolete?

The fear of losing market share is a commercial imperative experienced by all leading companies. In the microprocessor market, the first company to halve the size of a transistor would be able to produce twice as many microprocessors (at a lower cost) running twice as fast as the existing products. They could (and did) charge more for the latest, faster product, even though it cost them less than the previous version to manufacture.

Building cheaper, faster products is a means to an end; that end is receiving a decent return on the investment made. How large is the market for new microprocessors and how large an investment is required to build the next generation of products?

Rock’s law says that the cost of a chip fabrication plant doubles every four years (the per wafer price in the table above is increasing at a slower rate). Gambling hundreds of millions of dollars, later billions of dollars, on a next generation fabrication plant has always been a high risk/high reward investment.

The sales of microprocessors are dependent on the sale of computers that contain them, and people buy computers to enable them to use software. Microprocessor manufacturers thus have to both convince computer manufacturers to use their chip (without breaking antitrust laws) and convince software companies to create products that run on a particular processor.

The introduction of the IBM PC kick-started the personal computer market, with Wintel (the partnership between Microsoft and Intel) dominating software developer and end-user mindshare of the PC compatible market (in no small part due to the billions these two companies spent on advertising).

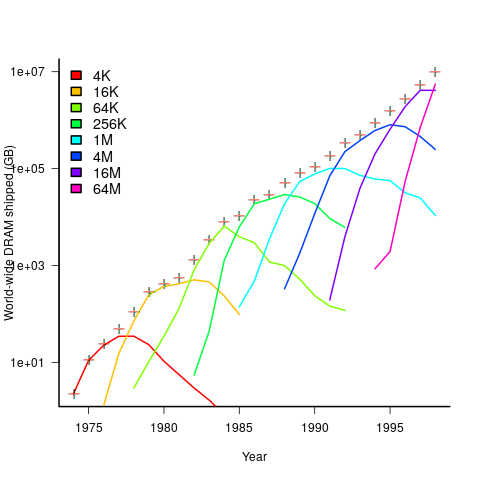

An effective technique for increasing the volume of microprocessors sold is to shorten the usable lifetime of the computer potential customers currently own. Customers buy computers to run software, and when new versions of software can only effectively be used in a computer containing more memory or on a new microprocessor which supports functionality not supported by earlier processors, then a new computer is needed. By obsoleting older products soon after newer products become available, companies are able to evolve an existing customer base to one where the new product is looked upon as the norm. Customers are force marched into the future.

The plot below shows sales volume, in gigabytes, of various sized DRAM chips over time. The simple story of exponential growth in sales volume (plus signs) hides the more complicated story of the rise and fall of succeeding generations of memory chips (code+data):

The Red Queens had a simple task, keep buying the latest products. The activities of the companies supplying the specialist equipment needed to build a chip fabrication plant has to be coordinated, a role filled by the International Technology Roadmap for Semiconductors (ITRS). The annual ITRS reports contain detailed specifications of the expected performance of the subsystems involved in the fabrication process.

Moore’s law is now dead, in that transistor doubling now takes longer than two years. Would transistor doubling time have taken longer than two years, or slowed down earlier, if:

- the ecosystem had not been dominated by two symbiotic companies, or did network effects make it inevitable that there would be two symbiotic companies,

- the Internet had happened at a different time,

- if software applications had quickly reached a good enough state,

- if cloud computing had gone mainstream much earlier.

Including natural language text topics in a regression model

The implementation records for a project sometimes include a brief description of each task implemented. There will be some degree of similarity between the implementation of some tasks. Is it possible to calculate the degree of similarity between tasks from the text in the task descriptions?

Over the years, various approaches to measuring document similarity have been proposed (more than you probably want to know about natural language processing).

One of the oldest, simplest and widely used technique is term frequency–inverse document frequency (tf-idf), which is based on counting word frequencies, i.e., is word context is ignored. This technique can work well when there are a sufficient number of words to ensure a good enough overlap between similar documents.

When the description consists of a sentence or two (i.e., a summary), the problem becomes one of sentence similarity, not document similarity (so tf-idf is unlikely to be of any use).

Word context, in a sentence, underpins the word embedding approach, which represents a word by an n-dimensional vector calculated from the local sentence context in which the word occurs (derived from a large amount of text). Words that are closer, in this vector space, are expected to have similar meanings. One technique for calculating the similarity between sentences is to compare the averages of the word embedding of the words they contain. However, care is needed; words appearing in the same context can create sentences having different meanings, as in the following (calculated sentence similarity in the comments):

import spacy nlp=spacy.load("en_core_web_md") # _md model needed for word vectors nlp("the screen is black").similarity(nlp("the screen is white")) # 0.9768339369182919 # closer to 1 the more similar the sentences nlp("implementing widgets would be little effort").similarity(nlp("implementing widgets would be a huge effort")) # 0.9636533803238744 nlp("the screen is black").similarity(nlp("implementing widgets would be a huge effort")) # 0.6596892830922606 |

The first pair of sentences are similar in that they are about the characteristics of an object (i.e., its colour), while the second pair are similar in that are about the quantity of something (i.e., implementation effort), and the third pair are not that similar.

The words in a document, or summary, are about some collection of topics. A set of related documents are likely to contain a discussion of a set of related topics in varying degrees. Latent Dirichlet allocation (LDA) is a widely used technique for calculating a set of (unseen) topics from a set of documents and their contained words.

A recent paper attempted to estimate task effort based on the similarity of the task descriptions (using tf-idf). My last semi-serious attempt to extract useful information from text, some years ago, was a miserable failure (it’s a very hard problem). Perhaps better techniques and tools are now available for me to leverage (my interest is in understanding what is going on, not making predictions).

My initial idea was to extract topics from task data, and then try to add these to regression models of task effort estimation, to see what impact they had. Searching to find out what researchers have recently been doing in this area, I was pleased to see that others were ahead of me, and had implemented R packages to do the heavy lifting, in particular:

- The

stmpackage supports the creation of Structural Topic Models; these add support for covariates to influence the process of fitting LDA models, i.e., a correlation between the topics and other variables in the data. Uses of STM appear to be oriented towards teasing out differences in topics associated with different values of some variable (e.g., political party), and the package authors have written papers analysing political data. - The

psychtmpackage supports what the authors call supervised latent Dirichlet allocation with covariates (SLDAX). This handles all the details needed to include the extracted LDA topics in a regression model; exactly what I was after. The user interface and documentation for this package is not as polished as thestmpackage, but the code held together as I fumbled my way through.

To experiment using these two packages I used the SiP dataset, which includes summary text for each task, and I have previously analysed the estimation task data.

The stm package:

The textProcessor function handles all the details of converting a vector of strings (e.g., summary text) to internal form (i.e., handling conversion to lower case, removing stop words, stemming, etc).

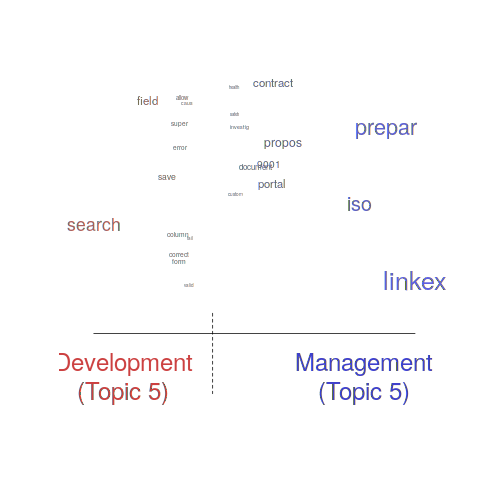

One of the input variables to the LDA process is the number of topics to use. Picking this value is something of a black art, and various functions are available for calculating and displaying concepts such as topic semantic coherence and exclusivity, the most commonly used words associated with a topic, and the documents in which these topics occur. Deciding the extent to which 10 or 15 topics produced the best results (values that sounded like a good idea to me) required domain knowledge that I did not have. The plot below shows the extent to which the words in topic 5 were associated with the Category column having the value “Development” or “Management” (code+data):

The psychtm package:

The prep_docs function is not as polished as the equivalent stm function, but the package’s first release was just last year.

After the data has been prepared, the call to fit a regression model that includes the LDA extracted topics is straightforward:

sip_topic_mod=gibbs_sldax(log(HoursActual) ~ log(HoursEstimate), data = cl_info,

docs = docs_vocab$documents, model = "sldax",

K = 10 # number of topics) |

where: log(HoursActual) ~ log(HoursEstimate) is the simplest model fitted in the original analysis.

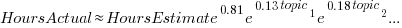

The fitted model had the form:  , with the calculated coefficient for some topics not being significant. The value

, with the calculated coefficient for some topics not being significant. The value  is close to that fitted in the original model. The value of

is close to that fitted in the original model. The value of  is the fraction of the

is the fraction of the  calculated to be present in the Summary text of the corresponding task.

calculated to be present in the Summary text of the corresponding task.

I’m please to see that a regression model can be improved by adding topics derived from the Summary text.

The SiP data includes other information such as work Category (e.g., development, management), ProjectCode and DeveloperId. It is to be expected that these factors will have some impact on the words appearing in a task Summary, and hence the topics (the stm analysis showed this effect for Category).

When the model formula is changed to: log(HoursActual) ~ log(HoursEstimate)+ProjectCode, the quality of fit for most topics became very poor. Is this because ProjectCode and topics conveyed very similar information, or did I need to be more sophisticated when extracting topic models? This needs further investigation.

Can topic models be used to build prediction models?

Summary text can only be used to make predictions if it is available before the event being predicted, e.g., available before a task is completed and the actual effort is known. My interest in model building is to understand the processes involved, so I am not worried about when the text was created.

My own habit is to update, or even create Summary text once a task is complete. I asked Stephen Cullen, my co-author on the original analysis and author of many of the Summary texts, about the process of creating the SiP Summary sentences. His reply was that the Summary field was an active document that was updated over time. I suspect the same is true for many task descriptions.

Not all estimation data includes as much information as the SiP dataset. If Summary text is one of the few pieces of information available, it may be possible to use it as a proxy for missing columns.

Perhaps it is possible to extract information from the SiP Summary text that is not also contained in the other recorded information. Having been successful this far, I will continue to investigate.

Tracking software evolution via its Changelog

Software that is used evolves. How fast does software evolve, e.g., much new functionality is added and how much existing functionality is updated?

A new software release is often accompanied by a changelog which lists new, changed and deleted functionality. When software is developed using a continuous release process, the changelog can be very fine-grained.

The changelog for the Beeminder app contains 3,829 entries, almost one per day since February 2011 (around 180 entries are not present in the log I downloaded, whose last entry is numbered 4012).

Is it possible to use the information contained in the Beeminder changelog to estimate the rate of growth of functionality of Beeminder over time?

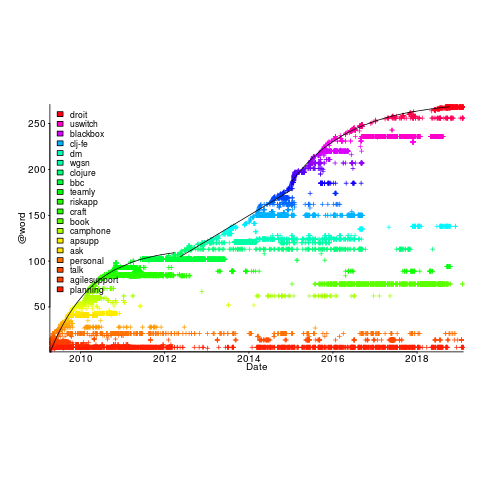

My thinking is driven by patterns in a plot of the Renzo Pomodoro dataset. Renzo assigned a tag-name (sometimes two) to each task, which classified the work involved, e.g., @planning. The following plot shows the date of use of each tag-name, over time (ordered vertically by first use). The first and third black lines are fitted regression models of the form  , where:

, where:  is a constant and

is a constant and  is the number of days since the start of the interval fitted; the second (middle) black line is a fitted straight line.

is the number of days since the start of the interval fitted; the second (middle) black line is a fitted straight line.

How might a changelog line describing a day’s change be distilled to a much shorter description (effectively a tag-name), with very similar changes mapping to the same description?

Named-entity recognition seemed like a good place to start my search, and my natural language text processing tool of choice is still spaCy (which continues to get better and better).

spaCy is Python based and the processing pipeline could have all been written in Python. However, I’m much more fluent in awk for data processing, and R for plotting, so Python was just used for the language processing.

The following shows some Beeminder changelog lines after stripping out urls and formatting characters:

Cheapo bug fix for erroneous quoting of number of safety buffer days for weight loss graphs. Bugfix: Response emails were accidentally off the past couple days; fixed now. Thanks to user bmndr.com/laur for alerting us! More useful subject lines in the response emails, like "wrong lane!" or whatnot. Clearer/conciser stats at bottom of graph pages. (Will take effect when you enter your next datapoint.) Progress, rate, lane, delta. Better handling of significant digits when displaying numbers. Cf stackoverflow.com/q/5208663 |

The code to extract and print the named-entities in each changelog line could not be simpler.

import spacy import sys nlp = spacy.load("en_core_web_sm") # load trained English pipelines count=0 for line in sys.stdin: count += 1 print(f'> {count}: {line}') # doc=nlp(line) # do the heavy lifting # for ent in doc.ents: # iterate over detected named-entities print(ent.lemma_, ent.label_) |

To maximize the similarity between named-entities appearing on different lines the lemmas are printed, rather than original text (i.e., words appear in their base form).

The label_ specifies the kind of named-entity, e.g., person, organization, location, etc.

This code produced 2,225 unique named-entities (5,302 in total) from the Beeminder changelog (around 0.6 per day), and failed to return a named-entity for 33% of lines. I was somewhat optimistically hoping for a few hundred unique named-entities.

There are several problems with this simple implementation:

- each line is considered in isolation,

- the change log sometimes contains different names for the same entity, e.g., a person’s full name, Christian name, or twitter name,

- what appear to be uninteresting named-entities, e.g., numbers and dates,

- the language does not know much about software, having been training on a corpus of general English.

Handling multiple names for the same entity would a lot of work (i.e., I did nothing), ‘uninteresting’ named-entities can be handled by post-processing the output.

A language processing pipeline that is not software-concept aware is of limited value. spaCy supports adding new training models, all I need is a named-entity model trained on manually annotated software engineering text.

The only decent NER training data I could find (trained on StackOverflow) was for BERT (another language processing tool), and the data format is very different. Existing add-on spaCy models included fashion, food and drugs, but no software engineering.

Time to roll up my sleeves and create a software engineering model. Luckily, I found a webpage that provided a good user interface to tagging sentences and generated the json file used for training. I was patient enough to tag 200 lines with what I considered to be software specific named-entities. … and now I have broken the NER model I built…

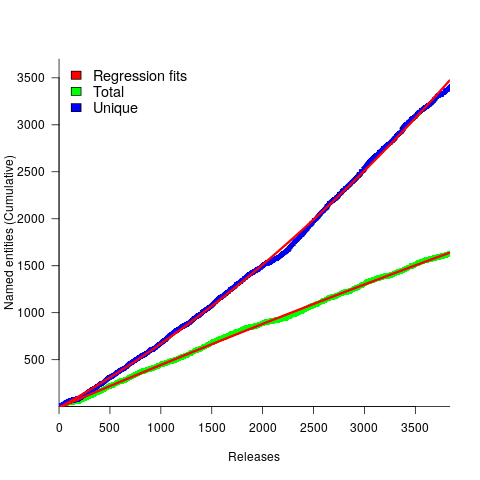

The following plot shows the growth in the total number of named-entities appearing in the changelog, and the number of unique named-entities (with the 1,996 numbers and dates removed; code+data);

The regression fits (red lines) are quadratics, slightly curving up (total) and down (unique); the linear growth components are: 0.6 per release for total, and 0.46 for unique.

Including software named-entities is likely to increase the total by at least 15%, but would have little impact on the number of unique entries.

This extraction pipeline processes one release line at a time. Building a set of Beeminder tag-names requires analysing the changelog as a whole, which would take a lot longer than the day spent on this analysis.

The Beeminder developers have consistently added new named-entities to the changelog over more than eleven years, but does this mean that more features have been consistently added to the software (or are they just inventing different names for similar functionality)?

It is not possible to answer this question without access to the code, or experience of using the product over these eleven years.

However, staying in business for eleven years is a good indicator that the developers are doing something right.

Join a crowdsourced search for software engineering data

Software engineering data, that can be made publicly available, is very rare; most people don’t attempt to collect data, and when data is collected, people rarely make any attempt to hang onto the data they do collect.

Having just one person actively searching for software engineering data (i.e., me) restricts potential sources of data to be English speaking and to a subset of development ecosystems.

This post is my attempt to start a crowdsourced campaign to search for software engineering data.

Finding data is about finding the people who have the data and have the authority to make it available (no hacking into websites).

Who might have software engineering data?

In the past, I have emailed chief technology officers at companies with less than 100 employees (larger companies have lawyers who introduce serious amounts of friction into releasing company data), and this last week I have been targeting Agile coaches. For my evidence-based software engineering book I mostly emailed the authors of data driven papers.

A lot of software is developed in India, China, South America, Russia, and Europe; unless these developers are active in the English-speaking world, I don’t see them.

If you work in one of these regions, you can help locate data by finding people who might have software engineering data.

If you want to be actively involved, you can email possible sources directly, alternatively I can email them.

If you want to be actively involved in the data analysis, you can work on the analysis yourself, or we can do it together, or I am happy to do it.

In the English-speaking development ecosystems, my connection to the various embedded ecosystems is limited. The embedded ecosystems are huge, there must be software data waiting to be found. If you are active within an embedded ecosystem, you can help locate data by finding people who might have software engineering data.

The email template I use for emailing people is below. The introduction is intended to create a connection with their interests, followed by a brief summary of my interest, examples of previous analysis, and the link to my book to show the depth of my interest.

By all means cut and paste this template, or create one that you feel is likely to work better in your environment. If you have a blog or Twitter feed, then tell them about it and why you think that evidence-based software engineering is important.

Be responsible and only email people who appear to have an interest in applying data analysis to software engineering. Don’t spam entire development groups, but pick the person most likely to be in a position to give a positive response.

This is a search for gold nuggets, and the response rate will be very low; a 10% rate of reply, saying sorry not data, would be better than what I get. I don’t have enough data to be able to calculate a percentage, but a ballpark figure is that 1% of emails might result in data.

My experience is that people are very unsure that anything useful will be found in their data. My response has been that I am always willing to have a look.

I always promise to anonymize their data, and not release it until they have agreed; but working on the assumption that the intent is to make a public release.

I treat the search as a background task, taking months to locate and email, say, 100-people considered worth sending a targeted email. My experience is that I come up with a search idea or encounter a blog post that suggests a line of enquiry, that may result in sending half-a-dozen emails. The following week, if I’m lucky, the same thing might happen again (perhaps with fewer emails). It’s a slow process.

If people want to keep a record of ideas tried, the evidence-based software engineering Slack channel could do with some activity.

Hello, A personalized introduction, such as: I have been reading your blog posts on XXX, your tweets about YYY, your youtube video on ZZZ. My interest is in trying to figure out the human issues driving the software process. Here are two detailed analysis of Agile estimation data: https://arxiv.org/abs/1901.01621 and https://arxiv.org/abs/2106.03679 My book Evidence-based Software Engineering discusses what is currently known about software engineering, based on an analysis of all the publicly available data. pdf+code+all data freely available here: http://knosof.co.uk/ESEUR/ and I'm always on the lookout for more software data. This email is a fishing request for software engineering data. I offer a free analysis of software data, provided an anonymised version of the data can be made public.

Recent Comments