Clustering source code within functions

The question of how best to cluster source code into functions is a perennial debate that has been ongoing since functions were first created.

Beginner programmers are told that clustering code into functions is good, for a variety of reasons (none of the claims are backed up by experimental evidence). Structuring code based on clustering the implementation of a single feature is a common recommendation; this rationale can be applied at both the function/method and file/class level.

The idea of an optimal function length (measured in statements) continues to appeal to developers/researchers, but lacks supporting evidence (despite a cottage industry of research papers). The observation that most reported fault appear in short functions is a consequence of most of a program’s code appearing in short functions.

I have had to deal with code that has not been clustered into functions. When microcomputers took off, some businessmen taught themselves to code, wrote software for their line of work and started selling it. If the software was a success, more functionality was needed, and the businessman (never encountered a woman doing this) struggled to keep on top of things. A common theme was a few thousand lines of unstructured code in one function in a single file (keeping everything in one file is also a trait of highly focus developers).

Adding structural bureaucracy (e.g., functions and multiple files) reduced the effort needed to maintain and enhance the code.

The problem with ‘born flat’ source is that the code for unrelated functionality is often intermixed, and global variables are freely used to communicate state. I have seen the same problems in structured function code, but instances are nowhere near as pervasive.

When implementing the same program, do different developers create functions implementing essentially the same functionality?

I am aware of two datasets relating to this question: 1) when implementing the same small specification (average length program 46.3 lines), a surprising number of variants (6,301) are created, 2) an experiment that asked developers to reintroduce functions into ‘flattened’ code.

The experiment (Alexey Braver’s MSc thesis) took an existing Python program, ‘flattened’ it by inlining functions (parameters were replaced by the corresponding call arguments), and asked subjects to “… partition it into functions in order to achieve what you consider to be a good design.”

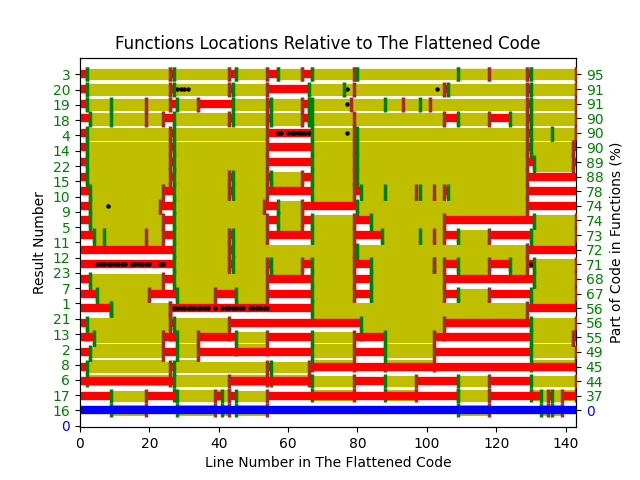

The 23 rows in the plot below show the start/end (green/brown delimited by blue lines) of each function created by the 23 subjects; red shows code not within a function, and right axis is percentage of each subjects’ code contained in functions. Blue line shows original (currently plotted incorrectly; patched original code+data):

There are many possible reasons for the high level of agreement between subjects, including: 1) the particular example chosen, 2) the code was already well-structured, 3) subjects were explicitly asked to create functions, 4) the iterative process of discovering code that needs to be written did not occur, 5) no incentive to leave existing working code as-is.

Given that most source has a short and lonely existence, is too much time being spent bike-shedding function contents?

Given how often lower level design time happens at code implementation time, perhaps discussion of function contents ought to be viewed as more about thinking how things fit together and interact, than about each function in isolation.

Analyzing each function in isolation can create perverse incentives.

Really interesting, and nice to see the solutions themselves do cohere well into ~two major flavors where the original was unstructured, but yeah this sort of flattening and refactoring puzzle can have obvious planes of cleavage, to borrow a metaphor. I think a good sequel would shuffle the original lines differently for each participant to see which end up grouped together and how frequently, maybe even pre-structure it into nonsensical functions to be replaced. The hard part is the ordering (original still has to be runnable, lines in the refactored versions will come however they may), but that’s doable.