Archive

Software_Engineering_Practices = Morals+Theology

Including the word science in the term used to describe a research field creates an aura of scientific enterprise. Universities name departments “Computer Science” and creationist have adopted the term “Creation Science”. The word engineering is used when an aura with a practical hue is desired, e.g., “Software Engineering” and “Consciousness Engineering”.

Science and engineering theories/models are founded on the principle of reproducibility. A theory/model achieves its power by making predictions that are close enough to reality.

Computing/software is an amalgam of many fields, some of which do tick the boxes associated with science and/or engineering practices, e.g., the study of algorithms or designing hardware. Activities whose output is primarily derived from human activity (e.g., writing software) are bedevilled by the large performance variability of people. Software engineering is unlikely to ever become a real engineering discipline.

If the activity known as software engineering is not engineering, then what is it?

To me, software engineering appears to be a form of moral theology. My use of this term is derived from the 1988 paper Social Science as Moral Theology by Neil Postman.

Summarising the term moral theology via its two components, i.e., morality+theology, we have:

Morality is a system of rules that enable people to live and work together for mutual benefit. Social groups operate better when its members cooperate with each other based on established moral rules. A group operating with endemic within group lying and cheating is unlikely to survive for very long. People cannot always act selfishly, some level of altruism towards group members is needed to enable a group to flourish.

Development teams will perform better when its members cooperate with each other, as opposed to ignoring or mistreating each other. Failure to successfully work together increases the likelihood that the project the team are working on will failure; however, it is not life or death for those involved.

The requirements of group living, which are similar everywhere, produced similar moral systems around the world.

The requirements of team software development are similar everywhere, and there does appear to be a lot of similarity across recommended practices for team interaction (although I have not studied this is detail and don’t have much data).

Theology is the study of religious beliefs and practices, some of which do not include a god, e.g., Nontheism, Humanism, and Religious Naturalism.

Religious beliefs provide a means for people to make sense of their world, to infer reasons and intentions behind physical events. For instance, why it rains or doesn’t rain, or why there was plenty of animal prey during last week’s hunt but none today. These beliefs also fulfil various psychological and emotional wants or needs. The questions may have been similar in different places, but the answers were essentially invented, and so different societies have ended up with different gods and theologies.

Different religions do have some features in common, such as:

- Creation myths. In software companies, employees tell stories about the beliefs that caused the founders to create the company, and users of a programming language tell stories about the beliefs and aims of the language designer and the early travails of the language implementation.

- Imagined futures, e.g., we all go to heaven/hell: An imagined future of software developers is that source code is likely to be read by other developers, and code lives a long time. In reality, most source code has a brief and lonely existence.

A moral rule sometimes migrates to become a religious rule, which can slow the evolution of the rule when circumstances change. For instance, dietary restrictions (e.g., must not eat pork) are an adaptation to living in some environments.

In software development, the morals of an Agile methodology perfectly fitted the needs of the early Internet, where existing ways of doing things did not exist and nobody knew what customers really wanted. The signatories of the Agile manifesto now have their opinions treated like those of a prophet (these 17 prophets are now preaching various creeds).

Agile is not always the best methodology to use, with a Waterfall methodology being a better match for some environments.

Now that the Agile methodology has migrated to become a ‘religious’ dogma, the reaction to suggestions that an alternative methodology be used are often what one would expect to questioning a religious belief.

For me this is an evolving idea.

Why did organizations fund the creation of the first computers?

What were the events that drove organizations to fund the creation of the first computers?

I suspect that many readers do not appreciate how long scientific/engineering calculations took before electronic computers became available, or the huge number of clerical staff employed to process the paperwork associated with running any sizeable business.

If somebody wanted to know the logarithm of some value, or the sine/cosine of an angle, they looked up the answer in a table. Individuals owned small booklets of tables supplying some level of granularity and number of significant digits. My school boy booklet contains 60-pages of tables, all to five digits of output accuracy, with logarithm supporting four-digit input values and the sine/cosine/tangent tables having an input granularity of hundredth of a degree.

The values in these tables were calculated by human computers; with the following being among the most well known (for more details, see Calculation and Tabulation in the Nineteenth Century: Airy versus Babbage by Doron Swade, and The History of Mathematical Tables: from Sumer to Spreadsheets edited by Campbell-Kelly, Croarken, Flood, and Robson):

- In 1624 Henry Briggs published logarithms for the integer ranges 1-20,000 and 90,001-100,000 (to 14 decimal places), followed some years later by tables of sine and logarithm of sine; in 1628 Adriaan Vlacq publishing tables that filled in the missing values (to 10 decimal places). In 1783 Jurij Vega published a bug-fixed and extended version of Vlacq’s tables.

In 1827 Charles Babbage (that Babbage) published Table of Logarithms of the Natural Numbers from 1 to 10800. These tables were based on corrected versions of these tables, a rigorous nine-stage proofreading process was followed to prevent new mistakes creeping in.

Today, one person can publish A reconstruction of the tables of Briggs’ Arithmetica logarithmica (1624), with an appendix containing 300 pages of calculated values,

- between 1794 and 1799, Gaspard de Prony employed sixty to eighty computers to calculate the logarithms of the integers from 1 to 200,000 to fifteen significant digits (rounding issues sometimes required calculating 25 decimal digits; published in eighteen volumes). Around 400 man-years.

Logarithms and trigonometric functions are very widely used, creating incentives for investing in calculating and publishing tables. While it may be financially worthwhile investing in producing tables for some niche markets (e.g. Life tables for insurance companies), there is an unmet demand that will only be filled by a dramatic drop in the cost of computing simple expressions.

Babbage’s Difference engine was designed to evaluate polynomial expressions and print the results; perfect for publishing tables. While Babbage did not build a Difference engine, starting in 1837, engines based on Babbage’s design were built and sold commercially by the Swede Per Georg Scheutz.

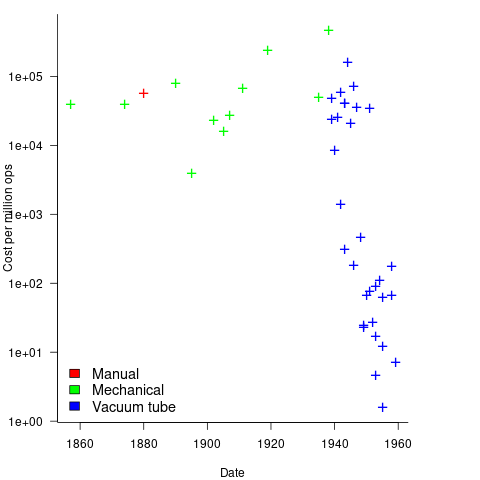

Mechanical calculators improve accuracy and speed the process up. Vacuum tubes are invented in 1904 and become widely used to process analogue signals. World War II created an urgent demand for the results of a variety of time-consuming calculations, e.g., accurate ballistic tables, and valve computers were built. The plot below shows the cost per million operations for manual, mechanical and valve computers (code+data):

To many observers at the start of the 1950s, the market for electronic computers appeared to be organizations who needed to perform large amounts of scientific/engineering calculation.

Most businesses perform simple calculations on many unrelated values, e.g., banks have to credit/debit the appropriate account when money is deposited/withdrawn. There is no benefit in having a machine that can perform hundreds of calculations per second unless it can be fed data fast enough to keep it busy.

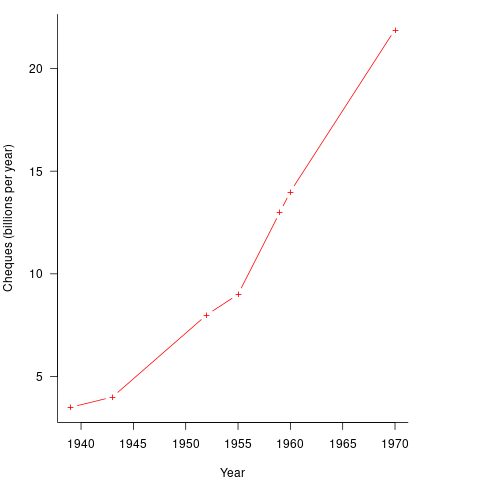

It so happened that, at the start of the 1950s, the US banking system was facing a crisis, the growth in the number of cheques being written meant that it would soon take longer than one day to process all the cheques that arrived in one day. In 1950 Bank of America managed 4.6 million checking accounts, and were opening 23,000 new account per month. Bank of America was then the largest bank in the world, and had a keen interest in continued growth. They funded the development of a bespoke computer system for processing cheques, the ERMA Banking system, which went live in 1959. The plot below shows the number of cheques processed per year by US banks (code+data):

The ERMA system included electronic storage for holding account details, and data entry was speeded up by encoding account details on a magnetic strip included within every cheque.

Businesses are very interested in an integrated combination of input devices plus electronic storage plus compute. There are more commerce oriented businesses than scientific/engineering businesses, and commercial businesses usually have a lot more money to spend, i.e., the real money to be made by selling computers was the business data processing market.

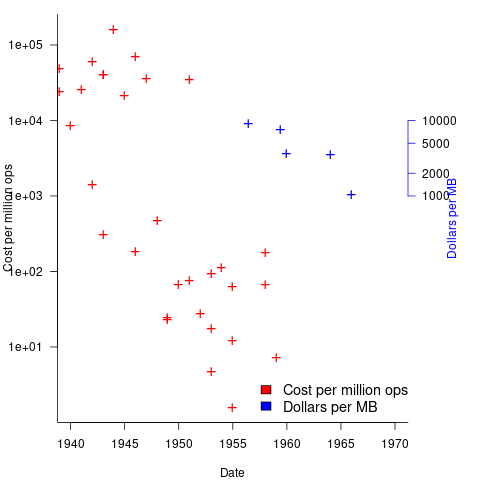

The plot below shows the decreasing cost of hard disc storage (blue, right axis), along with the decreasing computing cost of valve based computers (red, left axis; code+data):

There was a larger business demand to be able to store information electronically, and the hard disc was invented by IBM, roughly 15 years after the first electronic computers.

The very different application demands of data processing and scientific/engineering are reflected in the features supported by the two languages designed in the 1950s, and widely used for the rest of the century: Cobol and Fortran.

Data processing involves simple operations on large quantities of data stored in a potentially huge number of different combinations (the myriad of mechanical point-of-sale terminals stored data in a myriad of different formats, which evolved over time, and the demand for backward compatibility created spaghetti data well before spaghetti code existed). Cobol has extensive functionality supporting the layout and format of input and output data, and simplistic coding constructs.

Scientific/engineering code involves complex calculations on some amount of input. Fortran has extensive functionality supporting program control flow, and relatively basic support for data input/output.

A third major application domain is real-time processing, such as SAGE. However, data on this domain is very hard to find, so it is not discussed.

Describing software engineering in terms of a traditional science

If you were asked to describe the ‘building stuff’ side of software engineering, by comparing it with one of the traditional sciences, which science would you choose?

I think a lot of people would want to compare it with Physics. Yes, physics envy is not restricted to the softer sciences of humanities and liberal arts. Unlike physics, software engineering is not governed by a handful of simple ‘laws’, it’s a messy collection of stuff.

I used to think that biology had all the necessary important characteristics needed to explain software engineering: evolution (of code and products), species (e.g., of editors), lifespan, and creatures are built from a small set of components (i.e., DNA or language constructs).

Now I’m beginning to think that chemistry has aspects that are a better fit for some important characteristics of software engineering. Chemists can combine atoms of their choosing to create whatever molecule takes their fancy (subject to bonding constraints, a kind of syntax and semantics for chemistry), and the continuing existence of a molecule does not depend on anything outside of itself; biological creatures need to be able to extract some form of nutrient from the environment in which they live (which is also a requirement of commercial software products, but not non-commercial ones). Individuals can create molecules, but creating new creatures (apart from human babies) is still a ways off.

In chemistry and software engineering, it’s all about emergent behaviors (in biology, behavior is just too complicated to reliably say much about). In theory the properties of a molecule can be calculated from the known behavior of its constituent components (e.g., the electrons, protons and neutrons), but the equations are so complicated it’s impractical to do so (apart from the most simple of molecules; new properties of water, two atoms of hydrogen and one of oxygen, are still being discovered); the properties of programs could be deduced from the behavior its statements, but in practice it’s impractical.

What about the creative aspects of software engineering you ask? Again, chemistry is a much better fit than biology.

What about the craft aspect of software engineering? Again chemistry, or rather, alchemy.

Is there any characteristic that physics shares with software engineering? One that stands out is the ego of some of those involved. Describing, or creating, the universe nourishes large egos.

Recent Comments