Archive

My 2024 in software engineering

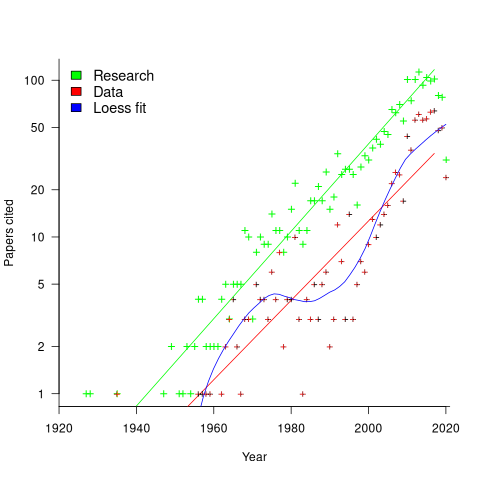

Readers are unlikely to have noticed something that has not been happening during the last few years. The plot below shows, by year of publication, the number of papers cited (green) and datasets used (red) in my 2020 book Evidence-Based Software Engineering. The fitted red regression lines suggest that the 20s were going to be a period of abundant software engineering data; this has not (yet?) happened (the blue line is a local regression fit, i.e., loess). In 2020 COVID struck, and towards the end of 2022 Large Language Models appeared and sucked up all the attention in the software research ecosystem, and there is lots of funding; data gathering now looks worse than boring (code+data):

LLMs are showing great potential as research tools, but researchers are still playing with them in the sandpit.

How many AI startups are there in London? I thought maybe one/two hundred. A recruiter specializing in AI staffing told me that he would estimate around four hundred; this was around the middle of the year.

What did I learn/discover about software engineering this year?

Regular readers may have noticed a more than usual number of posts discussing papers/reports from the 1960s, 1970s and early 1980s. There is a night and day difference between software engineering papers from this start-up period and post mid-1980s papers. The start-up period papers address industry problems using sophisticated mathematical techniques, while post mid-1980s papers pay lip service to industrial interests, decorating papers with marketing speak, such as maintainability, readability, etc. Mathematical orgasms via the study of algorithms could be said to be the focus of post mid-1980s researchers. So-called software engineering departments ought to be renamed as Algorithms department.

Greg Wilson thinks that the shift happened in the 1980s because this was the decade during which the first generation of ‘trained in software’ people (i.e., emphasis on mathematics and abstract ideas) became influential academics. Prior generations had received a practical training in physics/engineering, and been taught the skills and problem-solving skills that those disciplines had refined over centuries.

My research is a continuation of the search for answers to the same industrial problems addressed by the start-up researchers.

In the second half of the year I discovered the mathematical abilities of LLMs, and started using them to work through the equations for various models I had in mind. Sometimes the final model turned out to be trivial, but at least going through the process cleared away the complications in my mind. According to reports, OpenAI’s next, as yet unreleased, model has super-power maths abilities. It will still need a human to specify the equations to solve, so I am not expecting to have nothing to blog about.

Analysis/data in the following blog posts, from the last 12-months, belongs in my book Evidence-Based Software Engineering, in some form or other:

Small business programs: A dataset in the research void

Putnam’s software equation debunked (the book is non-committal).

if statement conditions, some basic measurements

Number of statement sequences possible using N if-statements; perhaps.

A new NASA software dataset from the 1970s

A surprising retrospective task estimation dataset

Average lines added/deleted by commits across languages

Census of general purpose computers installed in the 1960s

Some information on story point estimates for 16 projects

Agile and Waterfall as community norms

Median system cpu clock frequency over last 15 years

The evidence-based software engineering Discord channel continues to tick over (invitation), with sporadic interesting exchanges.

Finding reports and papers on the web

What is the best way to locate a freely downloadable copy of a report or paper on the web? The process I follow is outlined below (if you are new to this, you should first ask yourself whether reading a scientific paper will produce the result you are expecting):

- Google search. For the last 20 years, my experience is that Google search is the best place to look first.

Search on the title enclosed in double-quotes; if no exact matches are returned, the title you have may be slightly incorrect (variations in the typos of citations have been used to construct researcher cut-and-paste genealogies, i.e., authors copying a citation from a paper into their own work, rather than constructing one from scratch or even reading the paper being cited). Searching without quotes may return the desired result, or lots of unrelated matched. In the unrelated matches case, quote substrings within the title or include the first author’s surname.

The search may return a link to a ResearchGate page without a download link. There may be a “Request full-text” link. Clicking this sends a request email to one of the authors (assuming ResearchGate has an address), who will often respond with a copy of the paper.

A search may not return any matches, or links to copies that are freely available. Move to the next stage,

- Google Scholar. This is a fantastic resource. This site may link to a freely downloadable copy, even though a Google search does not. It may also return a match, even though a Google search does not. Most of the time, it is not necessary to include the title in quotes.

If the title matches a paper without displaying a link to a downloaded pdf, click on the match’s “Cited by” link (assuming it has one). The author may have published a later version that is available for download. If the citation count is high, tick the “Search within citing articles” box and try narrowing the search. For papers more than about five years old, you can try a “Customer range…” to remove more recent citations.

No luck? Move to the next stage,

- If a freely downloadable copy is available on the web, why doesn’t Google link to it?

A website may have a robots.txt requesting that the site not be indexed, or access to report/paper titles may be kept in a site database that Google does not access.

Searches now either need to be indirect (e.g., using Google to find an author web page, which may contain the sought after file), or targeted at specific cases.

It’s now all special cases. Things to try:

- Author’s website. Personal web pages are common for computing-related academics (much less common for non-computing, especially business oriented), but often a year or two out of date. Academic websites usually show up on a Google search. For new (i.e., less than a year), when you don’t need to supply a public link to the paper, email the authors asking for a copy. Most are very happy that somebody is interested in their work, and will email a copy.

When an academic leaves a University, their website is quickly removed (MIT is one of the few that don’t do this). If you find a link to a dead site, the Wayback Machine is the first place to check (try less recent dates first). Next, the academic may have moved to a new University, so you need to find it (and hope that the move is not so new that they have not yet created a webpage),

- Older reports and books. The Internet Archive is a great resource,

- Journals from the 1950s/1960s, or computer manuals. bitsavers.org is the first place to look,

- Reports and conference proceedings from before around 2000. It might be worth spending a few £/$ at a second hand book store; I use Amazon, AbeBooks, and Biblio. Despite AbeBooks being owned by Amazon, availability/pricing can vary between the two,

- A PhD thesis? If you know the awarding university, Google search on ‘university-name “phd thesis”‘ to locate the appropriate library page. This page will probably include a search function; these search boxes sometimes supporting ‘odd’ syntax, and you might have to search on: surname date, keywords, etc. Some universities have digitized thesis going back to before 1900, others back to 2000, and others to 2010.

The British Library has copies of thesis awarded by UK universities, and they have digitized thesis going back before 2000,

- Accepted at a conference. A paper accepted at a conference that has not yet occurred, maybe available in preprint form; otherwise you are going to have to email the author (search on the author names to find their university/GitHub webpage and thence their email),

- Both CiteSeer and then Semantic Scholar were once great resources. These days, CiteSeer has all but disappeared, and Semantic Scholar seems to mostly link to publisher sites and sometimes to external sites.

Dead-tree search techniques are a topic for history books.

More search suggestions welcome.

Conference vs Journal publication

Today is the start of the 2023 International Conference on Software Engineering (the 45’th ICSE, pronounced ick-see), the top ranked software systems conference and publication venue; this is where every academic researcher in the field wants to have their papers appear. This is a bumper year, of the 796 papers submitted 209 were accepted (26%; all numbers a lot higher than previous years), and there are 3,821 people listed as speaking/committee member/chairing session. There are also nine co-hosted conferences (i.e., same time/place) and twenty-two co-hosted workshops.

For new/niche conferences, the benefit of being co-hosted with a much larger conference is attracting more speakers/attendees. For instance, the International Conference on Technical Debt has been running long enough for the organizers to know how hard it is to fill a two-day program. The submission deadline for TechDebt 2023 papers was 23 January, six-weeks after researchers found out whether their paper had been accepted at ICSE, i.e., long enough to rework and submit a paper not accepted at ICSE.

Software research differs from research in many other fields in that papers published in major conferences have a greater or equal status compared to papers published in most software journals.

The advantage that conferences have over journals is a shorter waiting time between submitting a paper, receiving the acceptance decision, and accepted papers appearing in print. For ICSE 2023 the yes/no acceptance decision wait was 3-months, with publication occurring 5-months later; a total of 8-months. For smaller conferences, the time-intervals can be shorter. With journals, it can take longer than 8-months to hear about acceptance, which might only be tentative, with one or more iterations of referee comments/corrections before a paper is finally accepted, and then a long delay before publication. Established academics always have a story to tell about the time and effort needed to get one particular paper published.

In a fast changing field, ‘rapid’ publication is needed. The downside of having only a few months to decide which papers to accept, is that there is not enough time to properly peer-review papers (even assuming that knowledgable reviewers are available). Brief peer-review is not a concern when conference papers are refined to eventually become journal papers, but researchers’ time is often more ‘productively’ spent writing the next conference paper (productive in the sense of papers published per unit of effort), this is particularly true given that work invested in a journal publication does not automatically have the benefit of greater status.

The downside of rapid publication without follow-up journal publication, is the proliferation of low quality papers, and a faster fashion cycle for research topics (novelty is an important criterion for judging the worthiness of submitted papers).

Conference attendance costs (e.g., registration fee+hotel+travel+etc) can be many thousands of pounds/dollars, and many universities/departments will only fund those who to need to attend to present a paper. Depending on employment status, the registration fee for just ICSE is $1k+, with fees for each co-located events sometimes approaching $1k.

Conferences have ‘solved’ this speaker only funding issue by increasing the opportunities to present a paper, by, for instance, sessions for short 7-minute talks, PhD students, and even undergraduates (which also aids the selection of those with an aptitude for the publish or perish treadmill).

The main attraction of attending a conference is the networking opportunities it provides. Sometimes the only people at a session are the speakers and their friends. Researchers on short-term contracts will be chatting to Principle Investigators whose grant applications were recently approved. Others will be chatting to existing or potential collaborators; and there is always lots of socialising. ICSE even offers childcare for those who can afford to fly their children to Australia, and the locals.

There is an industrial track, but these are often treated as second class citizens, e.g., if a schedule clash occurs they will be moved or cancelled. There is even a software engineering in practice track. Are the papers on other tracks expected to be unconnected with software engineering practice, or is this an academic rebranding of work related to industry? While academics offer lip-service to industrial relevance, connections with industry are treated as a sign of low status.

In general, for people working in industry, I don’t think it’s worth attending an academic conference. Larger companies treat conferences as staff recruiting opportunities.

Are people working in industry more likely to read conference papers than journal papers? Are people working in industry more likely to read ICSE papers than papers appearing at other conferences?

My book Evidence Based Software Engineering cites 2,035 papers, and is a sample of one, of people working in industry. The following table shows the percentage of papers appearing in each kind of publication venue (code+data):

Published %

Journal 42

Conference 18

Technical Report 13

Book 11

Phd Thesis 3

Masters Thesis 2

In Collection 2

Unpublished 2

Misc 2 |

The 450 conference papers appeared at 285 different conferences, with 26% of papers appearing at the top ten conferences. The 871 journal papers appeared in 389 different journals, with 24% of the papers appearing in the top ten journals.

Count Conference 27 International Conference on Software Engineering 15 International Conference on Mining Software Repositories 14 European Software Engineering Conference 13 Symposium on the Foundations of Software Engineering 10 International Conference on Automated Software Engineering 8 International Symposium on Software Reliability Engineering 8 International Symposium on Empirical Software Engineering and Measurement 8 International Conference on Software Maintenance 7 International Conference on Software Analysis, Evolution, and Reengineering 7 International Conference on Program Comprehension Count Journal 28 Transactions on Software Engineering 27 Empirical Software Engineering 25 Psychological Review 21 PLoS ONE 19 The Journal of Systems and Software 18 Communications of the ACM 17 Cognitive Psychology 15 Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, & Cognition 14 Memory & Cognition 13 Psychonomic Bulletin & Review 13 Psychological Bulletin |

Transactions on Software Engineering has the highest impact factor of any publication in the field, and it and The Journal of Systems and Software rank second and third on the h5-index, with ICSE ranked first (in the field of software systems).

After scanning paper titles, and searching for pdfs, I have a to-study collection of around 20 papers and 10 associated datasets from this year’s ICSE+co-hosted.

Understanding where one academic paper fits in the plot line

Reading an academic paper is rather like watching an episode of a soap opera, unless you have been watching for a while you will have little idea of the roles played by the actors and the background to what is happening. A book is like a film in that it has a beginning-middle-end and what you need to know is explained.

Sitting next to somebody who has been watching for a while is a good way of quickly getting up to speed, but what do you do if no such person is available or ignores your questions?

How do you find out whether you are watching a humdrum episode or a major pivotal moment? Typing the paper’s title into Google, in quotes, can provide a useful clue; the third line of the first result returned will contain something like ’Cited by 219′ (probably a much lower number, with no ‘Cite by’ meaning ‘Cite by 0’). The number is a count of the other papers that cite the one searched on. Over 50% of papers are never cited and very recently published papers are too new to have any citations; a very few old papers accumulate thousands of citations.

Clicking on the ‘Cited by’ link will take you to Google Scholar and the list of later episodes involving the one you are interested in. Who are the authors of these later episodes (the names appear in the search results)? Have they all been written by the author of the original paper, i.e., somebody wandering down the street mumbling to himself? What are the citation counts of these papers? Perhaps the mumbler did something important in a later episode that attracted lots of attention, but for some reason you are looking at an earlier episode leading up to pivotal moment.

Don’t be put off by a low citation count. Useful work is not always fashionable and authors tend to cite what everybody else cites.

How do you find out about the back story? Papers are supposed to contain a summary of the back story of the work leading up to the current work, along with a summary of all related work. Page length restrictions (conferences invariably place a limit on the maximum length of a paper, e.g., 8 or 10 pages) mean that these summaries tend to be somewhat brief. The back story+related work summaries will cite earlier episodes, which you will then have to watch to find out a bit more about what is going on; yes, you guessed it, there is a rinse repeat cycle tracing episodes further and further back. If you are lucky you will find a survey article, which summarizes what is known based on everything that has been published up to a given point in time (in active fields surveys are published around every 10 years, with longer gaps in less active fields), or you will find the authors PhD thesis (this is likely to happen for papers published a few years after the PhD; a thesis is supposed to have a film-like quality to it and some do get published as books).

A couple of points about those citations you are tracing. Some contain typos (Google failing to return any matches for a quoted title is a big clue), some cite the wrong paper (invariable a cut-and-paste error by the author), some citations are only there to keep a referee happy (the anonymous people chosen to review a paper to decide whether it is worth publishing have been known to suggest their own work, or that of a friend be cited), some citations are only listed because everybody else cites them, and the cited work says the opposite of what everybody claims it says (don’t assume that just because somebody cites a paper that they have actually read it; the waterfall paper is the classic example of this).

After a week or two you should be up to speed on what is happening on the soap you are following.

Recent Comments