Archive

Number of statement sequences possible using N if-statements

I recently read a post by Terence Tao describing how he experimented with using ChatGPT to solve a challenging mathematical problem. A few of my posts contain mathematical problems I could not solve; I assumed that solving them was beyond my maths pay grade. Perhaps ChatGPT could help me solve some of them.

To my surprise, a solution was found to the first problem I tried.

I simplified the original problem (involving Motzkin numbers, details below) down to something that was easier for me to explain to ChatGPT. Based on ChatGPT’s response, it appeared lost, so I asked what it knew about Motzkin numbers. I then reframed the question around the concepts in its response, and got a response that, while reasonable, was not a solution. My question was not precise enough, and a couple of question/answer iterations later, ChatGPT broke the problem down into a series of steps that I saw could solve the problem. While the equation it used in its answer was just wrong, I knew what the correct equation was. So while ChatGPT frequently went off in the wrong direction and got its maths wrong, it helped me refine my statement of the problem and ChatGPT eventually gave steps to a solution which were blindingly obvious to me when I read them.

The question I wanted to answer was: How many distinct statement sequences can be created using

if-statements and  simple-statements (for a total of

simple-statements (for a total of  statements)?

statements)?

A simple-statement might be an assignment or function call, but not any kind of compound statement, such as a loop. Three sequences are possible using one if-statement and two simple-statements. The if-statement occupies two lines, i.e., the condition and termination curly-bracket, }, as follows:

s1; if (c1) { if (c1) { if (c1) { s1; s1; s2; s2; } } } s2; |

In a previous post I showed how a variant of this question, involving any number of if-statements, can be mapped to a combinatorial interpretation of Motzkin numbers and treating matching up/down diagonals along a path as an if-statement.

ChatGPT performed poorly when I phrased the problem in combinatorial terms (or perhaps my phrasing was poor), so I switched to using a lattice path approach. I asked: “How many lattice paths of length S containing exactly N occurrences of the step (1, 1) and N occurrences of the step (1, -1) are possible?”, and after reading the response I replied “Your analysis does not take into account the fact that the path cannot go below the x-axis. Rework your analysis to take this restriction into account.”

The following is my edited version of ChatGPT’s ‘solution’ response:

“Problem Restated:

We need to count the number of valid Dyck paths of length  , where the path consists of:

, where the path consists of:

Exactly  upward steps (1,1).

upward steps (1,1).

Exactly  downward steps (1,−1).

downward steps (1,−1).

The remaining steps (which must be  horizontal steps (1,0)).

horizontal steps (1,0)).

These paths must never dip below the x-axis, and they must return to the x-axis at the end.

…

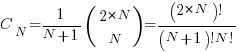

Step 2: Catalan Numbers for Balanced Paths

If we ignore the horizontal steps for the moment, the number of ways to place  upward steps and

upward steps and  downward steps such that the path does not go below the x-axis is given by the Catalan number

downward steps such that the path does not go below the x-axis is given by the Catalan number  :

:

This Catalan number counts the number of valid ways to arrange the  upward steps and

upward steps and  downward steps such that the path remains above or on the x-axis.

downward steps such that the path remains above or on the x-axis.

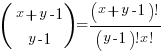

Step 3: Placing Horizontal Steps

Once the valid upward and downward steps have been arranged in a Catalan structure, we can freely place the  horizontal steps (1,0) in the remaining positions of the path. Since there are

horizontal steps (1,0) in the remaining positions of the path. Since there are  steps (upward and downward) and

steps (upward and downward) and  horizontal steps, there are

horizontal steps, there are  gaps (before, after, or between the upward/downward steps) where the horizontal steps can be placed.

gaps (before, after, or between the upward/downward steps) where the horizontal steps can be placed.

The number of ways to place  horizontal steps in these

horizontal steps in these  positions is given by a binomial coefficient:”

positions is given by a binomial coefficient:”

For some reason, ChatGPT gives the wrong binomial coefficient. Calculating the number of ways of distributing  items into

items into  bins is a well known problem; when a bin can contain zero items, the solution is:

bins is a well known problem; when a bin can contain zero items, the solution is:  .

.

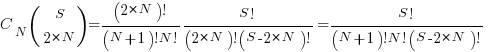

Combining the equations from the two steps gives the number of distinct statement sequences that can be created using

if-statements and  simple-statements as:

simple-statements as:

The above answer is technically correct, however, it fails to take into account that in practice an if-statement body will always contain either another if-statement or a simple statement, i.e., the innermost if-statement of any nested sequence cannot be empty (the equation used for distributing items into bins assumes a bin can be empty).

Rather than distributing  statements into

statements into  gaps, we first need to insert one simple statement into each of the innermost if-statements. The number of ways of distributing the remaining statements are then counted as previously. How many innermost if-statements can be created using

gaps, we first need to insert one simple statement into each of the innermost if-statements. The number of ways of distributing the remaining statements are then counted as previously. How many innermost if-statements can be created using  if-statements? I found the answer to this question in a StackExchange question, using traditional search.

if-statements? I found the answer to this question in a StackExchange question, using traditional search.

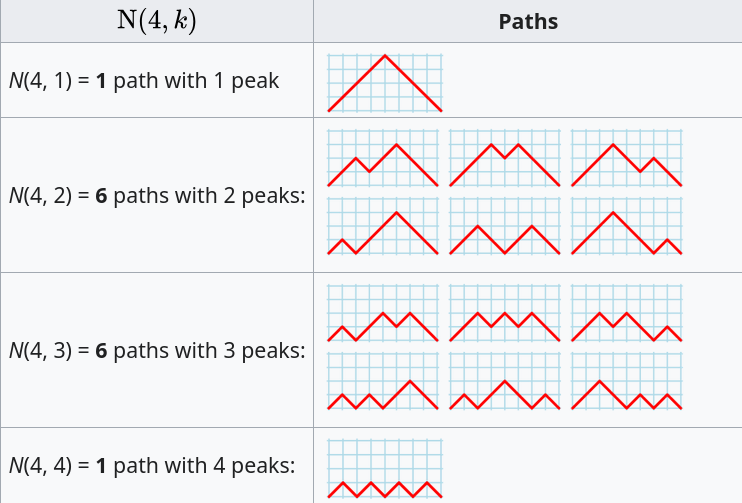

The question can be phrased in terms of peaks in Dyck paths, and the answer is contained in the Narayana numbers (which I had never heard of before). The following example, from Wikipedia, shows the number of paths containing a given number of peaks, that can be produced by four if-statements:

The sum of all these paths is the Catalan number for the given number of if-statements, e.g., using  to denote the Narayana number:

to denote the Narayana number:  .

.

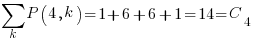

Adding at least one simple statement to each innermost if-statement changes the equation for the number of statement sequences from  , to:

, to:

The following table shows the number of distinct statement sequences for five-to-twenty statements containing one-to-five if-statements:

N if-statements

1 2 3 4 5

5 6 1

6 10 6

7 15 20 1

8 21 50 7

9 28 105 29 1

10 36 196 91 9

11 45 336 238 45 1

12 55 540 549 166 11

S 13 66 825 1,155 504 66

14 78 1,210 2,262 1,332 286

15 91 1,716 4,179 3,168 1,002

16 105 2,366 7,351 6,930 3,014

17 120 3,185 12,397 14,157 8,074

18 136 4,200 20,153 27,313 19,734

19 153 5,440 31,720 50,193 44,759

20 171 6,936 48,517 88,458 95,381 |

The following is an R implementation of the calculation:

Narayana=function(n, k) choose(n, k)*choose(n, k-1)/n

Catalan=function(n) choose(2*n, n)/(n+1)

if_stmt_possible=function(S, N)

{

return(Catalan(N)*choose(S, 2*N)) # allow empty innermost if-statement

}

if_stmt_cnt=function(S, N)

{

if (S <= 2*N)

return(0)

total=0

for (k in 1:N)

{

P=Narayana(N, k)

if (S-P*k >= 2*N)

total=total+P*choose(S-P*k, 2*N)

}

return(total)

}

isc=matrix(nrow=25, ncol=5)

for (S in 5:20)

for (N in 1:5)

isc[S, N]=if_stmt_cnt(S, N)

print(isc) |

Distribution of add/multiply expression values

The implementation of scientific/engineering applications requires evaluating many expressions, and can involve billions of adds and multiplies (divides tend to be much less common).

Input values percolate through an application, as it is executed. What impact does the form of the expressions evaluated have on the shape of the output distribution; in particular: What is the distribution of the result of an expression involving many adds and multiplies?

The number of possible combinations of add/multiply grows rapidly with the number of operands (faster than the rate of growth of the Catalan numbers). For instance, given the four interchangeable variables: w, x, y, z, the following distinct expressions are possible: w+x+y+z, w*x+y+z, w*(x+y)+z, w*(x+y+z), w*x*y+z, w*x*(y+z), w*x*y*z, and w*x+y*z.

Obtaining an analytic solution seems very impractical. Perhaps it’s possible to obtain a good enough idea of the form of the distribution by sampling a subset of calculations, i.e., the output from plugging random values into a large enough sample of possible expressions.

What is needed is a method for generating random expressions containing a given number of operands, along with a random selection of add/multiply binary operators, then to evaluate these expressions with random values assigned to each operand.

The approach I used was to generate C code, and compile it, along with the support code needed for plugging in operand values (code+data).

A simple method of generating postfix expressions is to first generate operations for a stack machine, followed by mapping this to infix form to a postfix form.

The following awk generates code of the form (‘executing’ binary operators, o, right to left): o v o v v. The number of variables in an expression, and number of lines to generate, are given on the command line:

# Build right to left function addvar() { num_vars++ cur_vars++ expr="v " expr # choose variable later } function addoperator() { cur_vars-- expr="o " expr # choose operator later } function genexpr(total_vars) { cur_vars=2 num_vars=2 expr="v v" # Need two variables on stack while (num_vars <= total_vars) { if (cur_vars == 1) # Must push a variable addvar() else if (rand() > 0.2) # Seems to produce reasonable expressions addvar() else addoperator() } while (cur_vars > 1) # Add operators to use up operands addoperator() print expr } BEGIN { # NEXPR and VARS are command line options to awk if (NEXPR != "") num_expr=NEXPR else num_expr=10 for (e=1; e <=num_expr; e++) genexpr(VARS) } |

the following awk code maps each line of previously generated stack machine code to a C expression, wraps them in a function, and defines the appropriate variables.

function eval(tnum) { if ($tnum == "o") { printf("(") tnum=eval(tnum+1) #recurse for lhs if (rand() <= PLUSMUL) # default 0.5 printf("+") else printf("*") tnum=eval(tnum) #recurse for rhs printf(")") } else { tnum++ printf("v[%d]", numvars) numvars++ # C is zero based } return tnum } BEGIN { numexpr=0 print "expr_type R[], v[];" print "void eval_expr()" print "{" } { numvars=0 printf("R[%d] = ", numexpr) numexpr++ # C is zero based eval(1) printf(";\n") next } END { # print "return(NULL)" printf("}\n\n\n") printf("#define NUMVARS %d\n", numvars) printf("#define NUMEXPR %d\n", numexpr) printf("expr_type R[NUMEXPR], v[NUMVARS];\n") } |

The following is an example of a generated expression containing 100 operands (the array v is filled with random values):

R[0] = ((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((( ((((((((((((((((((((((((v[0]*v[1])*v[2])+(v[3]*(((v[4]* v[5])*(v[6]+v[7]))+v[8])))*v[9])+v[10])*v[11])*(v[12]* v[13]))+v[14])+(v[15]*(v[16]*v[17])))*v[18])+v[19])+v[20])* v[21])*v[22])+(v[23]*v[24]))+(v[25]*v[26]))*(v[27]+v[28]))* v[29])*v[30])+(v[31]*v[32]))+v[33])*(v[34]*v[35]))*(((v[36]+ v[37])*v[38])*v[39]))+v[40])*v[41])*v[42])+v[43])+ v[44])*(v[45]*v[46]))*v[47])+v[48])*v[49])+v[50])+(v[51]* v[52]))+v[53])+(v[54]*v[55]))*v[56])*v[57])+v[58])+(v[59]* v[60]))*v[61])+(v[62]+v[63]))*v[64])+(v[65]+v[66]))+v[67])* v[68])*v[69])+v[70])*(v[71]*(v[72]*v[73])))*v[74])+v[75])+ v[76])+v[77])+v[78])+v[79])+v[80])+v[81])+((v[82]*v[83])+ v[84]))*v[85])+v[86])*v[87])+v[88])+v[89])*(v[90]+v[91])) v[92])*v[93])*v[94])+v[95])*v[96])*v[97])+v[98])+v[99])*v[100]); |

The result of each generated expression is collected in an array, i.e., R[0], R[1], R[2], etc.

How many expressions are enough to be a representative sample of the vast number that are possible? I picked 250. My concern was the C compilers code generator (I used gcc); the greater the number of expressions, the greater the chance of encountering a compiler bug.

How many times should each expression be evaluated using a different random selection of operand values? I picked 10,000 because it was a big number that did not slow my iterative trial-and-error tinkering.

The values of the operands were randomly drawn from a uniform distribution between -1 and 1.

What did I learn?

- Varying the number of operands in the expression, from 25 to 200, had little impact on the distribution of calculated values.

- Varying the form of the expression tree, from wide to deep, had little impact on the distribution of calculated values.

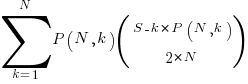

- Varying the relative percentage of add/multiply operators had a noticeable impact on the distribution of calculated values. The plot below shows the number of expressions (binned by rounding the absolute value to three digits) having a given value (the power law exponents fitted over the range 0 to 1 are: -0.86, -0.61, -0.36; code+data):

A rationale for the change in the slopes, for expressions containing different percentages of add/multiply, can be found in an earlier post looking at the distribution of many additions (the Irwin-Hall distribution, which tends to a Normal distribution), and many multiplications (integer power of a log).

- The result of many additions is to produce values that increase with the number of additions, and spread out (i.e., increasing variance).

- The result of many multiplications is to produce values that become smaller with the number of multiplications, and become less spread out.

Which recent application spends a huge amount of time adding/multiplying values in the range -1 to 1?

Large language models. Yes, under the hood they are all linear algebra; adding and multiplying large matrices.

LLM expressions are often evaluated using a half-precision floating-point type. In this 16-bit type, the exponent is biased towards supporting very small values, at the expense of larger values not being representable. While operations on a 10-bit significand will experience lots of quantization error, I suspect that the behavior seen above not noticeable change.

Motzkin paths and source code silhouettes

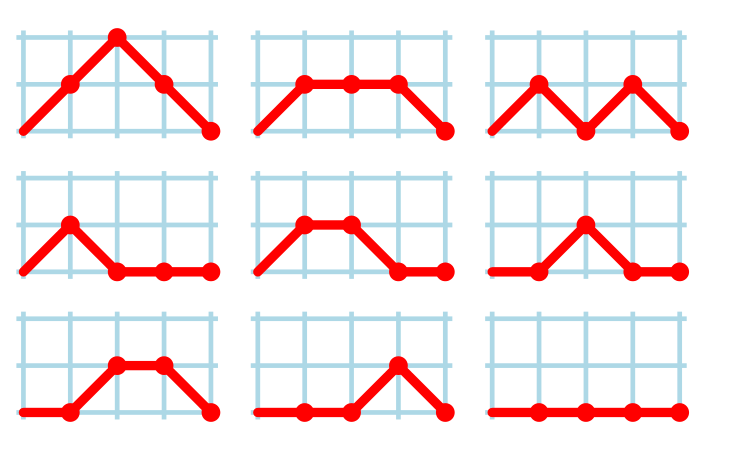

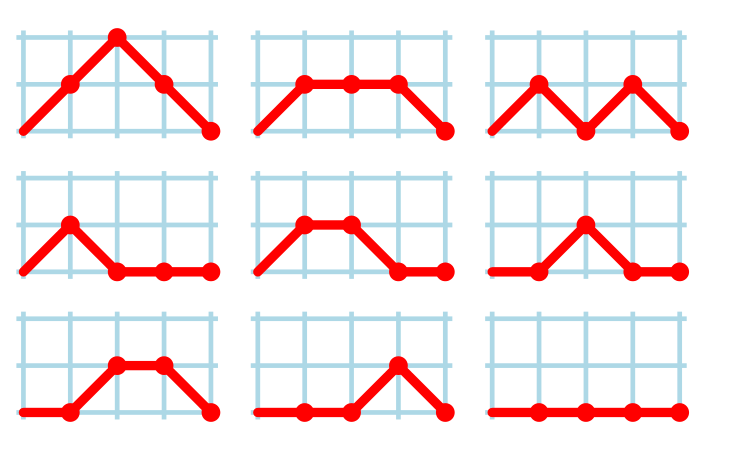

Consider a language that just contains assignments and if-statements (no else arm). Nesting level could be used to visualize programs written in such a language; an if represented by an Up step, an assignment by a Level step, and the if-terminator (e.g., the } token) by a Down step. Silhouettes for the nine possible four line programs are shown in the figure below (image courtesy of Wikipedia). I use the term silhouette because the obvious terms (e.g., path and trace) have other common usage meanings.

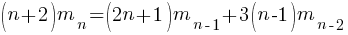

How many silhouettes are possible, for a function containing  statements? Motzkin numbers provide the answer; the number of silhouettes for functions containing from zero to 20 statements is: 1, 1, 2, 4, 9, 21, 51, 127, 323, 835, 2188, 5798, 15511, 41835, 113634, 310572, 853467, 2356779, 6536382, 18199284, 50852019. The recurrence relation for Motzkin numbers is (where

statements? Motzkin numbers provide the answer; the number of silhouettes for functions containing from zero to 20 statements is: 1, 1, 2, 4, 9, 21, 51, 127, 323, 835, 2188, 5798, 15511, 41835, 113634, 310572, 853467, 2356779, 6536382, 18199284, 50852019. The recurrence relation for Motzkin numbers is (where  is the total number of steps, i.e., statements):

is the total number of steps, i.e., statements):

Human written code contains recurring patterns; the probability of encountering an if-statement, when reading code, is around 17% (at least for the C source of some desktop applications). What does an upward probability of 17% do to the Motzkin recurrence relation? For many years I have been keeping my eyes open for possible answers (solving the number theory involved is well above my mathematics pay grade). A few days ago I discovered weighted Motzkin paths.

A weighted Motzkin path is one where the Up, Level and Down steps each have distinct weights. The recurrence relationship for weighted Motzkin paths is expressed in terms of number of colored steps, where:  is the number of possible colors for the Level steps, and

is the number of possible colors for the Level steps, and  is the number of possible colors for Down steps; Up steps are assumed to have a single color:

is the number of possible colors for Down steps; Up steps are assumed to have a single color:

setting:  and

and  (i.e., all kinds of step have one color) recovers the original relation.

(i.e., all kinds of step have one color) recovers the original relation.

The different colored Level steps might be interpreted as different kinds of non-nesting statement sequences, and the different colored Down steps might be interpreted as different ways of decreasing nesting by one (e.g., a goto statement).

The connection between weighted Motzkin paths and probability is that the colors can be treated as weights that add up to 1. Searching on “weighted Motzkin” returns the kind of information I had been looking for; it seems that researchers in other fields had already discovered weighted Motzkin paths, and produced some interesting results.

If an automatic source code generator outputs the start of an if statement (i.e., an Up step) with probability  , an assignment (i.e., a Level step) with probability

, an assignment (i.e., a Level step) with probability  , and terminates the

, and terminates the if (i.e., a Down step) with probability  , what is the probability that the function will contain at least

, what is the probability that the function will contain at least  statements? The answer, courtesy of applying Motzkin paths in research into clone cell distributions, is:

statements? The answer, courtesy of applying Motzkin paths in research into clone cell distributions, is:

![P_n=sum{i=0}{delim{[}{(n-2)/2}{]}}(matrix{2}{1}{{n-2} {2i}})C_{2i}a^{i}b^{n-2-2i}c^{i+1} P_n=sum{i=0}{delim{[}{(n-2)/2}{]}}(matrix{2}{1}{{n-2} {2i}})C_{2i}a^{i}b^{n-2-2i}c^{i+1}](https://shape-of-code.com/wp-content/plugins/wpmathpub/phpmathpublisher/img/math_951_57086dac25a2ff31c2230f0791800e35.png)

where:  is the

is the  ‘th Catalan number, and that

‘th Catalan number, and that [...] is a truncation; code for an implementation in R.

In human written code we know that  , because the number of statements in a compound-statement roughly has an exponential distribution (at least in C).

, because the number of statements in a compound-statement roughly has an exponential distribution (at least in C).

There has been some work looking at the number of peaks in a Motzkin path, with one formula for the total number of peaks in all Motzkin paths of length n. A formula for the number of paths of length  , having

, having  peaks, would be interesting.

peaks, would be interesting.

Motzkin numbers have been extended to what is called higher-rank, where Up steps and Level steps can be greater than one. There are statements that can reduce nesting level by more than one, e.g., breaking out of loops, but no constructs increase nesting by more than one (that I can think of). Perhaps the rather complicated relationship can be adapted to greater Down steps.

Other kinds of statements can increase nesting level, e.g., for-statements and while-statements. I have not yet spotted any papers dealing with the case where an Up step eventually has a corresponding Down step at the appropriate nesting level (needed to handle different kinds of nest-creating constructs). Pointers welcome. A related problem is handling if-statements containing else arms, here there is an associated increase in nesting.

What characteristics does human written code have that results in it having particular kinds of silhouettes? I have been thinking about this for a while, but have no good answers.

If you spot any Motzkin related papers that you think could be applied to source code analysis, please let me know.

Update

A solution to the Number of statement sequences possible using N if-statements problem.

Recent Comments