Archive

The first computer I owned

The first computer I owned was a North Star Horizon. I bought it in kit form, which meant bags of capacitors, resistors, transistors, chips, printed circuit boards, etc, along with the circuit diagrams for each board. These all had to be soldered in the right holes, the chips socketed (no surface mount soldering for such a low volume system), and wires connected. I was amazed when the system booted the first time I powered it up; debugging with the very basic equipment I had would have been a nightmare. The only missing component was the power supply transformer, and a trip to the London-based supplier sorted that out. I saved a months’ salary by building the kit (which cost me 4-months salary, and I was one of the highest paid people in my circle).

The few individuals who bought a computer in the late 1970s bought either a Horizon or a Commodore Pet (which was more expensive, but came with an integrated monitor and keyboard). Computer ownership really started to take off when the BBC micro came along at the end of 1981, and could be bought for less than a months’ salary (at least for a white-collar worker).

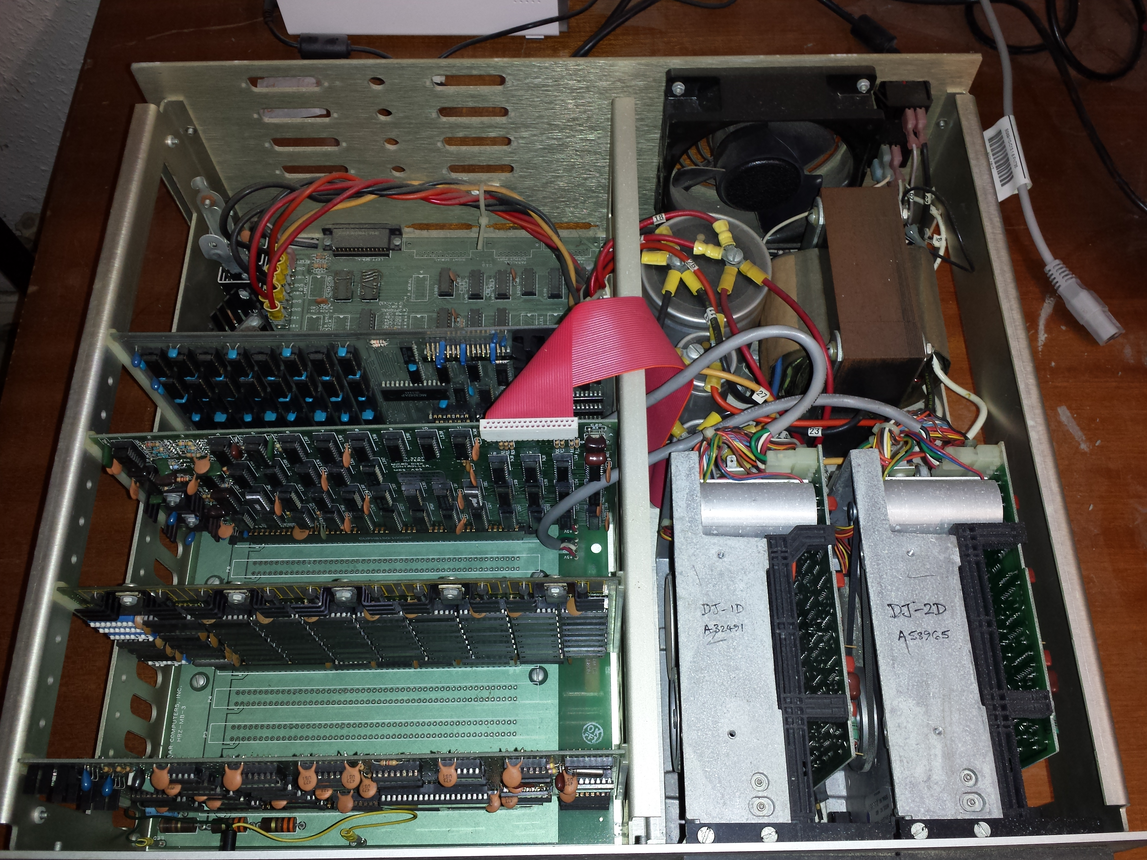

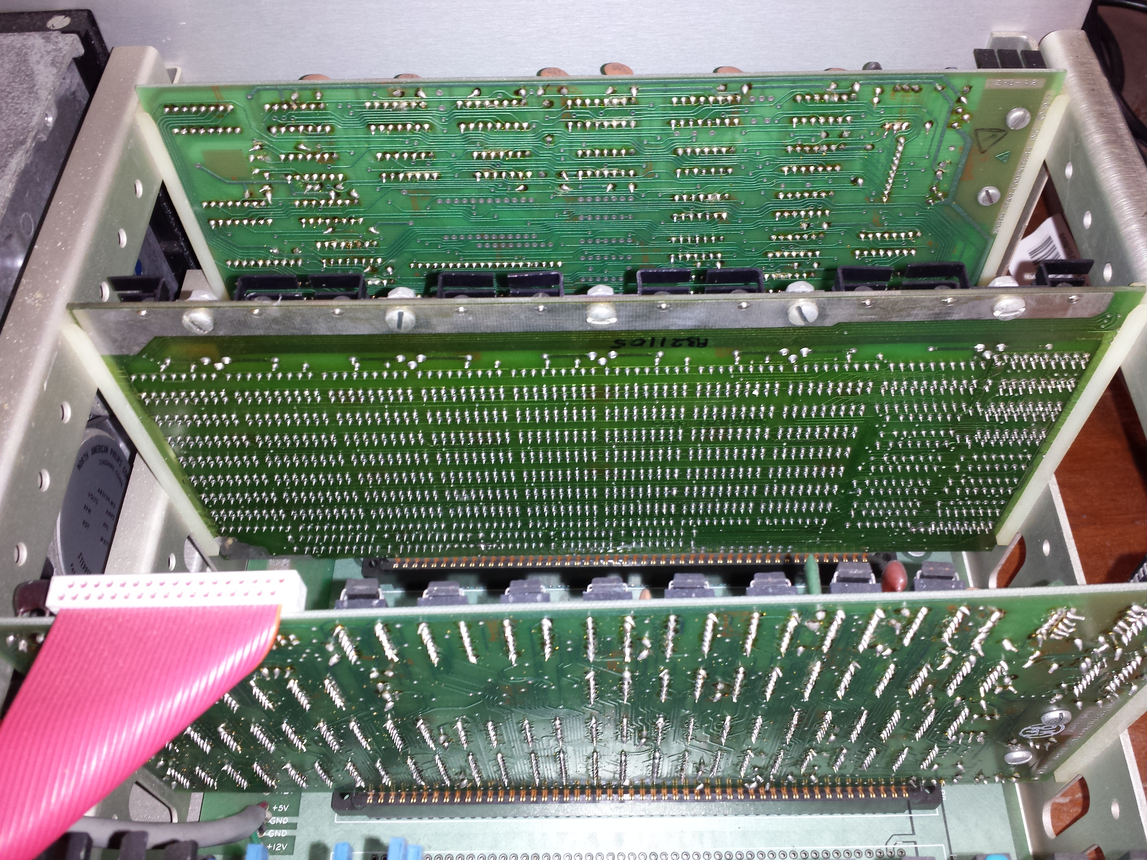

My Horizon contained a Z80A clocking at 4MHz, 32K of RAM, and two 5 1/4-inch floppy drives (each holding 360K; the Wikipedia article says the drives held 90K, mine {according to the labels on the floppies, MD 525-10} are 40-track, 10-sector, double density). I later bought another 32K of memory; the system ROM was at 56K, and contained 4K of code, various tricks allowed the 4K above 60K to be used (the consistent quality of the soldering on one of the boards below identifies the non-hand built board).

The OS that came with the system was CP/M, renamed to CP/M-80 when the Intel 8086 came along, and will be familiar to anybody used to working with early versions of MS-DOS.

As a fan of Pascal, my development environment of choice was UCSD Pascal. The C compiler of choice was BDS C.

Horizon owners are total computer people 🙂 An emulator, running under Linux and capable of running Horizon disk images, is available for those wanting a taste of being a Horizon owner. I didn’t see any mention of audio emulation in the documentation; clicks and whirls from the floppy drive were a good way of monitoring compile progress without needing to look at the screen (not content with using our Horizon’s at home, another Horizon owner and I implemented a Horizon emulator in Fortran, running on the University’s Prime computers). I wonder how many Nobel-prize winners did their calculations on a Horizon?

The Horizon spec needs to be appreciated in the context of its time. When I worked in application support at the University of Surrey, users had a default file allocation of around 100K’ish (memory is foggy). So being able to store stuff on a 360K floppy, which could be purchased in boxes of 10, was a big deal. The mainframe/minicomputers of the day were available with single-digit megabytes, but many previous generation systems had under 100K of RAM. There were lots of programs out there still running in 64K. In terms of cpu power, nearly all existing systems were multi-user, and a less powerful, single-user, cpu beats sharing a more powerful cpu with 10-100 people.

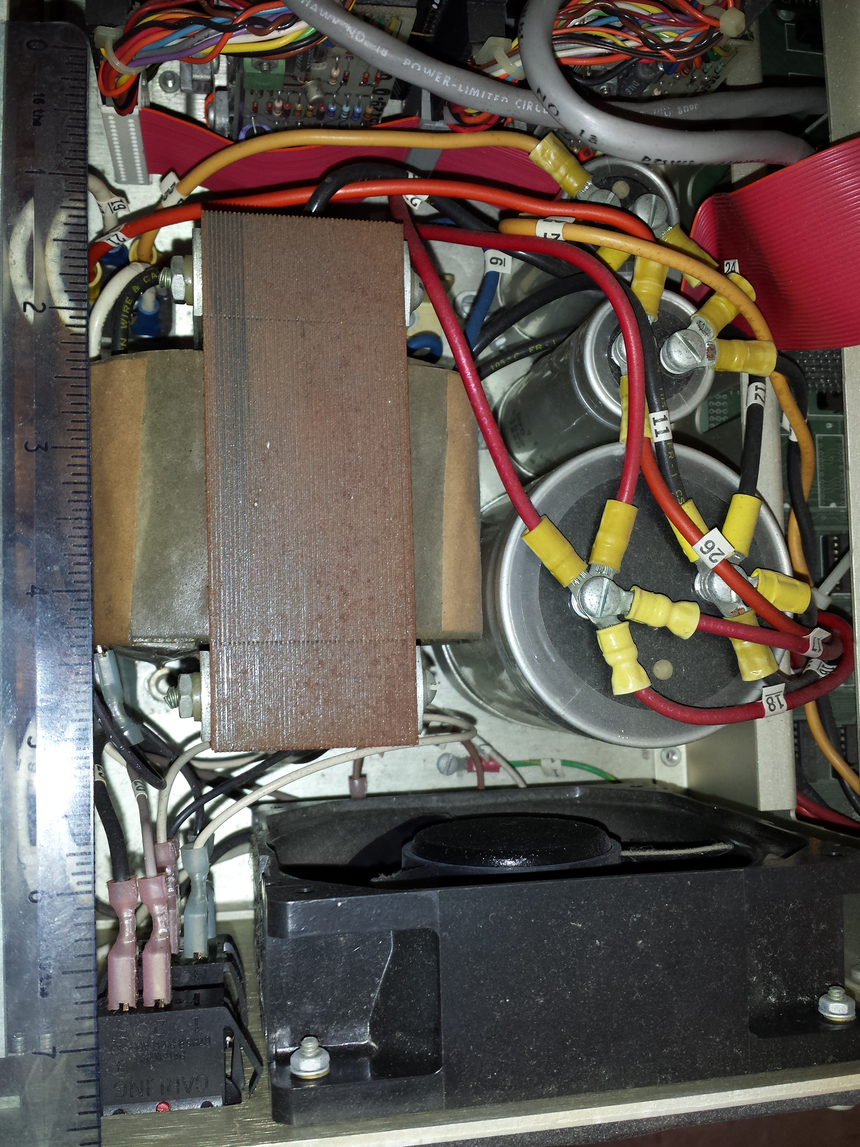

In terms of sheer weight, visual appearance and electrical clout, the Horizon power supply far exceeds those seen in today’s computers, which look tame by comparison (two of those capacitors are 4-inches tall):

My Horizon has been sitting in the garage for 32-years, and tucked away in unused rooms for years before that. The main problem with finding out whether it still works is finding a device to connect to the 25-pin serial port. I have an old PC with a 9-pin serial port, but I have spent enough of my life fiddling around with serial-port cables and Kermit to be content trying a simpler approach. I connect the power supply and switched it on. There was a loud crack and a flash on the disk-controller board; probably a tantalum capacitor giving up the ghost (easy enough to replace). The primary floppy drive did spin up and shutdown after some seconds (as expected), but the internal floppy engagement arm (probably not its real name) does not swing free when I open the bay door (so I cannot insert a floppy).

I am hoping to find a home for it in a computer museum, and have emailed the two closest museums. If these museums are not interested, the first person to knock on my door can take it away, along with manuals and floppies.

Update: This North Star can now be seen at the Retro Computer Museum.

The oldest compiler still in production use is?

What is the oldest compiler still in production use?

A CHILL compiler I worked on a long time ago has probably been in production use for 30 years now.

Code gets added and deleted from production software all the time, how might ‘oldest’ be measured? I propose using the mean age of every line of code, including comments, where the age of a line is reset to zero when it is modified in any way (excluding code formatting).

The following are two environmental factors that enable a production compiler to get very old:

- a relatively obscure language: popular languages have new compilers written for them (compiler death through competition) or have new features added to them (requiring new lines of code which could even displace ‘aged’ code),

- a very long-lived application associated with the language: obscure languages tend to be very quickly abandoned in the dust of history unless they have a symbiotic relationship with an important application,

- very long-lived host hardware and target processor: changing either often requires substantial new code or a move to a newer compiler. For ancient the only candidate is the IBM 370 and just really old the Intel 80×80, Zilog Z80.

Virtual machines provide a mechanism to be host hardware independent. The Micro Focus Cobol had a rewrite in the early 1990s (it might have had others since) and I don’t think UCSD Pascal I.5 is still used for production work.

Fortran is an evolving language and very popular in some application domains. I doubt there are any (mean age) old Fortran compilers in production use.

Why do I put forward the ITT (in its International Telephone & Telegraph days, these bits subsequently sold off) CHILL compiler as potentially the oldest compiler currently in production use?

- Obscure language and long-lived application (telephone switching software),

- host hardware was IBM 370 family, target processor Intel 8086 (later updated to support 80386),

- large development team and very small support team (i.e., lots of old code and small changes over the years),

- single customer, i.e., no push to add features to attract new customers or keep existing ones.

My last conversation with anybody associated with this compiler was a chance meeting over 10 years ago, so I might be a bit out of date.

30+ year old source code for compilers can be downloaded (e.g., the original PDP 11 C compiler) but these compilers are not in production use (forgotten about military installations anybody?)

I welcome other proposals for the oldest compiler currently in production use.

Recent Comments