Archive

Open source: monoculture is more desirable than portability

An oft repeated fable is that open source software is portable, all thanks to C and Unix. The reality is that open source lives in an environment that is evolving to become a monoculture that does not require portability, this is being driven by the law of the jungle.

First some background and history. Portability requires that source code have the same behavior on different platforms, or rather than programs built from that code have the same behavior, this requires that:

- all compilers assign the same semantics to a given piece of code,

- all operating systems include support the same set of libraries in the same way.

If you want portability across lots of compilers then Fortran has stood head and shoulders above the competition for decades. Now some C folk may point out that they have been compiling some large code base for decades, with few changes necessitated by compiler differences; yes this has been possible in certain niche markets where there is a dominant supplier who has a vested interest in not breaking customer code. C has a long history of widespread large variation in behavior of across compilers.

What about Cobol you ask? Cobol is all about data manipulation and unless you have data in the format expected by a Cobol program you have no need for that program. Nobody cares about portable Cobol programs unless they are also interested in portable data.

If you want portability across lots of operating systems the solution has always been to minimise the dependency on system/third-party library calls (to the extent of including source code for functionality often supported by an OS). The reason for minimising OS dependency is the huge variation in support for different libraries and a wide range of behaviors for supposedly the same functionality. But you say, Unix is an OS that did/does provide a common set of libraries that have the same behavior; no, this is history seen through rose tinted glasses as anyone who knows about the Unix wars will tell you.

In the last century, to experience ‘portability’ Unix developers had to live in a monoculture of either PDP-11s or Sun workstations.

Open source, as it existed in the 1970s, 80s and into the 90’s was Fortran code that ran on a surprisingly wide range of OS/cpu/compilers, along with a smattering of other languages. Back then there were not many software applications and when they did exist many were written in Fortran (Oracle being an early, lots of Fortran, example), this created a strong incentive for vendors to support a Fortran compiler that did things the same way as everybody else (which did not prevent them adding proprietary goodies to try and lure customers towards lock-in).

How did we get to today’s dominance of C and Unix? Easy, evolution at a rate that caused competitors to die out until there was a last man standing. That last man standing was gcc and Linux. The portability problem has been solved by removing the need to port code; it is compiled by the same compiler to run on the same cpu (Intel x86 family) to run under the same OS (Linux).

Of course some of today’s open source C is compiled using non-gcc compilers, but the percentage is small and specialised (a lot of the older code is portable because it used to exist in a multi-compiler/cpu/OS world and had to evolve into being portable). The gcc competitor, llvm, is working long and hard to ensure compatibility and somehow has to differentiate itself while being compatible, a tough fight for developer hearts and minds.

Differences in CPU characteristics are a big headache to any compiler writer wanting to support identical behavior across platforms; having a single cpu family as the market leader more or less solves this problem. ARM has become a major player in the CPU world, but it shares many developer visible characteristics with Intel x86 (e.g., 32-bit int, 64-bit long, pointer and ints are the same size and IEEE floating-point) and options are available for handling some of the other potential differences (e.g., right shift of signed integers).

The Unix wars have not gone away, they have moved to more far flung battlefields leaving behind some hard fought over common ground. Anybody who wants to see the scares left by these war only needs to look at the #ifs in system headers or the parameters selected inside .configure files.

Having everybody use the same compiler/cpu/OS saves having to make a huge time/money investment in making software portable, at least until the invention of photonic computers or the arrival of aliens (whose computers are unlikely to contain a CPU that shares Intel/ARM characteristics or have the same libraries as Linux).

C/Linux has not won in the sense that competitors have given up; in 20 years time the majority of open source in active use might be Javascript running inside a browser.

Popularity of Open source Operating systems over time

Surveys of operating system usage trends are regularly published and we get to read about how the various Microsoft products are doing and the onward progress of mobile OSs; sometimes Linux gets an entry at the bottom of the list, sometimes it is just ‘others’ and sometimes it is both.

Operating systems are pervasive and a variety of groups actively track reported faults in order to issue warnings to the public; the volume of OS fault informations available makes it an obvious candidate for testing fault prediction models (e.g., how many faults will occur in a given period of time). A very interesting fault history analysis of OpenBSD in a paper by Ozment and Schechter recently caught my eye and I wondered if the fault time-line could be explained by the time-line of OpenBSD usage (e.g., more users more faults reported). While collecting OS usage information is not the primary goal for me I thought people would be interested in what I have found out and in particular to share the OS usage data I have managed to obtain.

How might operating system usage be measured? Analyzing web server logs is an obvious candidate method; when a web browser requests information many web servers write information about the request to a log file and this information sometimes includes the name of the operating system on which the browser is running.

Other sources of information include items sold (licenses in Microsoft’s case, CDs/DVD’s for Open source or perhaps books {but book sales tend not to be reported in the way programming language book sales are reported}) and job adverts.

For my time-line analysis I needed OpenBSD usage information between 1998 and 2005.

The best source of information I found, by far, of Open source OS usage derived from server logs (around 138 million Open source specific entries) is that provided by Distrowatch who count over 700 different distributions as far back as 2002. What is more Ladislav Bodnar the founder and executive editor of DistroWatch was happy to run a script I sent him to extract the count data I was interested in (I am not duplicating Distrowatch’s popularity lists here, just providing the 14 day totals for OS count data). Some analysis of this data below.

As luck would have it I recently read a paper by Diomidis Spinellis which had used server log data to estimate the adoption of Open Source within organizations. Diomidis researches Open source and was willing to run a script I wrote to extract the User Agent string from the 278 million records he had (unfortunately I cannot make this public because it might contain personal information such as email addresses, just the monthly totals for OS count data, tar file of all the scripts I used to process this raw log data; the script to try on your own logs is countos.sh).

My attempt to extract OS names from the list of User Agent strings Diomidis sent me (67% of of the original log entries did contain a User Agent string) provides some insight into the reliability of this approach to counting usage (getos.awk is the script to try on the strings extracted with the earlier script). There is no generally agreed standard for:

- what information should be present; 6% of UA strings contained no OS name that I knew (this excludes those entries that were obviously robots/crawlers/spiders/etc),

- the character string used to specify a given OS or a distribution; the only option is to match a known list of names (OS names used by Distrowatch,

missos.awkis the tar file script to print out any string not containing a specified list of OS names, the Wikipedia List of operating systems article), - quality assurance; some people cannot spell ‘windows’ correctly and even though the source is now available I don’t think anybody uses CP/M to access the web (at least 91 strings,

%, would not have passed).

%, would not have passed).

Ladislav Bodnar thinks that log entries from the same IP addresses should only be counted once per day per OS name. I agree that this approach is much better than ignoring address information; why should a person who makes 10 accesses be counted 10 times, a person who makes one access is only counted once. It is possible that two or more separate machines running the same OS are accessing the Internet through a common gateway that results in them having the IP address from an external server’s point of view; this possibility means that the Distrowatch data undercounts the unique accesses (not a serious problem if most visitors have direct Internet access rather than through a corporate network).

The Distrowatch data includes counts for all IP address and from 13 May 2004 onwards unique IP address per day per OS. The mean ratio between these two values, summed over all OS counts within 14 day periods, is 1.9 (standard deviation 0.08) and the Pearson correlation coefficient between them is 0.987 (95% confidence interval is 0.984 to 0.990), i.e., almost perfect correlation.

The Spinellis data ignores IP address information (I got this dataset first, and have already spent too much time collecting to do more data extraction) and has 10 million UA strings containing Open source OS names (6% of all OS names matched).

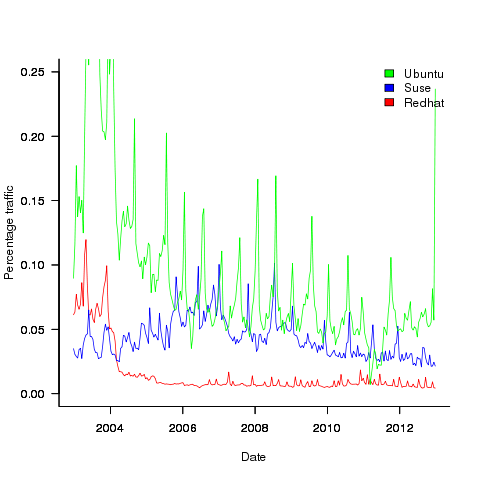

How representative are the Distrowatch and Spinellis data? The data is as representative of the general OS population as the visitors recorded in the respective server logs are representative of OS usage. The plot below shows the percentage of visitors to Distrowatch that use Ubuntu, Suse, Redhat. Why does Redhat, a very large company in the Open source world, have such a low percentage compared to Ubuntu? I imagine because Redhat customers get their updates from Redhat and don’t see a need to visit sites such as Distrowatch; a similar argument can be applied to Suse. Perhaps the Distrowatch data underestimates those distributions that have well known websites and users who have no interest in other distributions. I have not done much analysis of the Spinellis data.

Presumably the spikes in usage occur around releases of new versions, I have not checked.

For my analysis I am interested in relative change over time, which means that representativeness and not knowing the absolute number of OSs in use is not a problem. Researchers interested in a representative sample or estimating the total number of OSs in use are going to need a wider selection of data; they might be interested in the following OS usage information I managed to find (yes I know about Netcraft, they charge money for detailed data and I have not checked what the Wayback Machine has on file):

- Wikimedia has OS count information back to 2009. Going forward this is a source of log data to rival Distrowatch’s, but the author of the scripts probably ought to update the list of OS names matched against,

- w3schools has good summary data for many months going back to 2003,

- statcounter has good summary data (daily, weekly, monthly) going back to 2008,

- TheCounter.com had data from 2000 to 2009 (csv file containing counts obtained from Wayback Machine).

If any reader has or knows anybody who has detailed OS usage data please consider sharing it with everybody.

Recent Posts

Tags

Archives

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

- April 2010

- March 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

- December 2009

- November 2009

- October 2009

- September 2009

- August 2009

- July 2009

- June 2009

- May 2009

- April 2009

- March 2009

- February 2009

- January 2009

- December 2008

Recent Comments