Archive

The difference is significant

A statement that invariably appears in the published results of empirical studies comparing some property of two or more sets of numbers is that the difference is significant (if the difference is not significant, the paper is unlikely to be published). Here, the use of the word significant is the shortened form of the term statistically significant.

It is possible that two sets of measurements just so happen to have, for instance, the same/different mean value. Statistical significance is an estimate of the likelihood that an observed result is unlikely to have occurred by chance. The mechanics of calculating a numeric value for statistical significance can be complicated; the commonly seen p-value applies to a particular kind of statistical significance.

The fact that a difference is unlikely to have occurred by chance does not mean that the magnitude of the difference is of any practical use, or of any theoretical interest.

How large must a difference be to make it of practical use?

When I was in the business of selling code optimization tools for microcomputer software, a speed/code size improvement of at least 10% was needed before a worthwhile number of people were likely to pay for the software (a few would pay for less, and a few wanted more improvements before they would pay). I would not be surprised to find that very different percentages were applicable in other developer ecosystems.

In software engineering research papers, presentation of the practical use of work is often nothing more than a marketing pitch by the authors, not a list of estimated usefulness for different software ecosystems.

These days the presentation of material in empirical software engineering papers is often organized around a series of research questions, e.g., “How does X vary across projects?”, “Does the presence of X significantly impact the issue resolution time?”. One or more of these research questions are pitched as having practical relevance, and the statistical significance of the results is presented as vindication of this claimed relevance. Getting a paper published requires that those asked to review agree that the questions it asks and answers are interesting.

This method of paper organization and presentation is not unique to researchers in software engineering. To attract funding, all researchers need to actively promote the value of their wares.

The problem I have with software engineering papers is the widespread use of simplistic techniques (e.g., a Wilcoxon signed-rank test to check the significance of the difference between the means of two samples), and reporting little more than p-value significance; yes, included plots may sometimes be visually appealing, but other times just confused.

If researchers fitted regression models to their data, it becomes possible to estimate the contribution made by each of the attributes measured to the observed behavior. Surprisingly often, the size of the contribution is relatively small, while still being statistically significant.

By not building regression models, software researchers are cluttering up the list of known statistically significant behaviors with findings about factors whose small actual contribution makes it unlikely that they will be of practical interest.

The aura of software quality

Bad money drives out good money, is a financial adage. The corresponding research adage might be “research hyperbole incentivizes more hyperbole”.

Software quality appears to be the most commonly studied problem in software engineering. The reason for this is that use of the term software quality imbues what is said with an aura of relevance; all that is needed is a willingness to assert that some measured attribute is a metric for software quality.

Using the term “software quality” to appear relevant is not limited to researchers; consultants, tool vendors and marketers are equally willing to attach “software quality” to whatever they are selling.

When reading a research paper, I usually hit the delete button as soon as the authors start talking about software quality. I get very irritated when what looks like an interesting paper starts spewing “software quality” nonsense.

The paper: A Family of Experiments on Test-Driven Development commits the ‘crime’ of framing what looks like an interesting experiment in terms of software quality. Because it looked interesting, and the data was available, I endured 12 pages of software quality marketing nonsense to find out how the authors had defined this term (the percentage of tests passed), and get to the point where I could start learning about the experiments.

While the experiments were interesting, a multi-site effort and just the kind of thing others should be doing, the results were hardly earth-shattering (the experimental setup was dictated by the practicalities of obtaining the data). I understand why the authors felt the need for some hyperbole (but 12-pages). I hope they continue with this work (with less hyperbole).

Anybody skimming the software engineering research literature will be dazed by the number and range of factors appearing to play a major role in software quality. Once they realize that “software quality” is actually a meaningless marketing term, they are back to knowing nothing. Every paper has to be read to figure out what definition is being used for “software quality”; reading a paper’s abstract does not provide the needed information. This is a nightmare for anybody seeking some understanding of what is known about software engineering.

When writing my evidence-based software engineering book I was very careful to stay away from the term “software quality” (one paper on perceptions of software product quality is discussed, and there are around 35 occurrences of the word “quality”).

People in industry are very interested in software quality, and sometimes they have the confusing experience of talking to me about it. My first response, on being asked about software quality, is to ask what the questioner means by software quality. After letting them fumble around for 10 seconds or so, trying to articulate an answer, I offer several possibilities (which they are often not happy with). Then I explain how “software quality” is a meaningless marketing term. This leaves them confused and unhappy. People have a yearning for software quality which makes them easy prey for the snake-oil salesmen.

Main memory: the crucial component that vendors don’t mention

CPU performance hogs the limelight when people discuss the year-on-year increases in computing power that used to occur.

This focus on cpu performance was/is driven by marketing, the people with the money either don’t want customers thinking about the performance impact of main memory size or speed, or want them to treat the processor as the most important component of a computer. Vendors want processor performance to drive customer purchase decisions.

Hardware manufacturers used to entice new customers with low cost machines, containing minimal memory. Once a customer started to use their shiny new computer, they found that it did save them lots of time and money, but also they needed more memory (which could only be brought from the manufacturer and was not cheap).

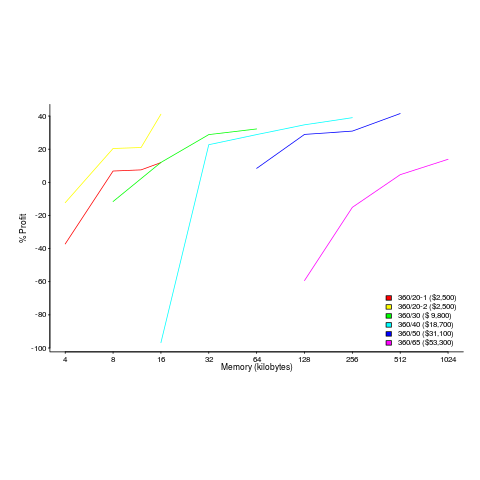

The plot below shows the prices IBM charged for System 360s, in 1966. Anti-trust investigations uncover all kinds of interesting data, like selling low-spec equipment at a loss to entice customers and make life difficult for competitors (code+data for all plots).

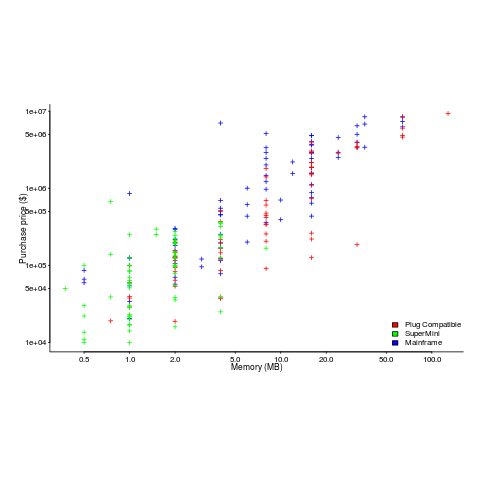

The plot below (data from the 19 Aug 1985 issue of ComputerWorld) shows how the price of computers increased as the minimum about of memory they supported increased.

Yes, in 1985 top end computers came with over 50M of memory; but most customers thought themselves lucky if they had a few megabytes.

If the processor is slow, it just takes longer for programs to run. If the computer does not have enough memory, programs cannot run. For most applications memory requirements are addressed first, followed by processor performance; memory requirements is the number one issue. The optimizations that commercial compilers could perform were limited by the memory capacity of developer machines.

Intel’s main line of business used to be selling memory chips, but these chips became commodity items as more companies entered the market; Intel bet the farm on selling processors and the rest is history. As a seller of a unique product it was/is in Intel’s interest to spend lots of money on marketing the benefits of processor performance; sellers of commodity items (such as memory chips) don’t have nearly as much to gain from generic product marketing, because customers may choose to buy from other sellers (in such markets sellers have to concentrate on marketing themselves).

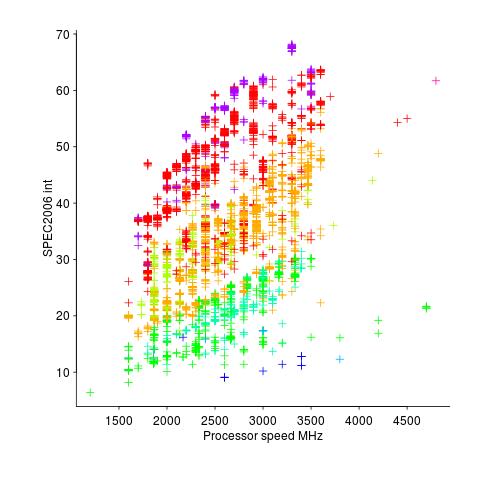

Memory capacity/speed and cpu speed are two aspects of system performance; they need to be balanced to meet customer drive application requirements. The plot below shows the SPEC cpu integer performance of 4,332 systems running at various clock rates; the colors denote the different peak memory transfer rates of the memory chips in these systems (code+data).

These days (and perhaps in the past, I don’t have any data), memory performance is a much better predictor of system performance, but vendors don’t have an incentive to market this fact.

Recent Comments