Archive

Socrates 2014 unconference in the UK

I was at the Socrates unconference at the end of last week. An unconference is a conference with no prearranged speakers, the attendees turn up and some of them volunteer to talk about a topic of their choosing on the day. The talks were structured as half a dozen parallel sessions of an hour each in rooms dotted around two different buildings.

I had previously been to half a dozen or so of the London Software Craftsmanship meetups (there is a large overlap in the organizers of the two groups) and thought I had some understanding of how the community went about building software engineering knowledge. At the end of the first day this understanding underwent a major revamp (the arts and craft movement struck me as something of a parallel).

Based on the experience of one meeting I would say that the Socrates’ community approach to achieving the goals laid out in the Manifesto for Software Craftsmanship (as exemplified by those present at unconference) is primarily a social one based on personal experiences and shared experiences communicated through meetings and pair programming (yes, pair programming).

A great deal of pair programming was constantly going on and a person’s recent experience of pairing with somebody-or-other was a perfectly natural topic to bring up in casual conversation. I have never seen this kind of widespread community practice of interaction on a detailed before; I think it is great and I hope it spreads.

I volunteered to talk Friday morning about “When is it worth investing in reducing maintenance costs?” (I now have more data than used in my blog post on the topic). The talk did not go well in the sense that while people appeared to understood the analysis they did not seem to understand why anybody would want to use the decision making approach proposed. I got the same impression from people who asked me about the topic during food breaks (I had given a lightening talk Thursday evening with about half the attendees present).

The argument I made was that improving software is an investment intended to reduce future maintenance activities; like all investments the person making it wants receive a worthwhile return on the risk they are taking. The talk derived a requirement on the investment/benefit ratio needed for a code improvement activity to at least break even.

Now I am not always the world’s greatest communicator, so peoples’ lack of understanding may have been down to poor presentation on my part. But, in the evening, thinking about everything I had seen during the day I realised that my proposal for driving code improvement decisions using an economic model ran counter to the spirit of software craftsmanship as practiced by those present. This is not to say that the software craftsman are anti-economics, but that they want to be proud of their work and require that it meet certain personal and community standards, which may mean being less than economically efficient in some cases. At your average developer conference I would have expected zero interest, but here I had made the mistake of underestimating the strong craft influence and the socially derived approach (rather than trying to use experimental evidence) to finding solutions to software engineering problems.

There were a handful of people at the meeting interested in working towards a scientific approach to obtaining solutions to software engineering problems, i.e., using evidence derived from experiments. At one of the sessions a small group of us talked about how the software craftsman community might help researchers interested in experimental research (perhaps by helping to find professional subjects or by being willing to spend time discussing industry problems). I made my usual appeal for data that could be made public.

I suspect that many software craftsman would be interested in monitoring their own performance and that it would be worthwhile providing pointers to tools and techniques that might be used. Watch this space for progress.

The most interesting session I went to was by Steve Hayes who talked about his experience of starting and running a transparent company (this involves making information that companies usually keep confidential, such as employee, public). I had read about such companies before but this was my first encounter with somebody who had done it in practice.

The event appeared to run itself very smoothly, probably as much due to the invisible hard work of the organizers as much as the more visible attendee work. I would recommend the host venue, Farncombe conference centre, to anyone wanting to run a conference with lots of breakout rooms and social spaces. The food was high quality and artistically presented, demanding that both desserts on the menu be consumed.

Anybody who is in a rush to experience a Socrates unconference can visit Germany in August (a contingent from the UK are already booked).

Has the seed that gets software development out of the stone-age been sown?

A big puzzle for archaeologists is why Stone Age culture lasted as long as it did (from approximately 2.5 millions years ago until the start of the copper age around 6.3 thousand years ago). Given the range of innovation rates seen in various cultures through-out human history, a much shorter Stone Age is to be expected. A recent paper proposes that low population density is what maintained the Stone Age status quo; there was not enough contact between different hunter gather groups for widespread take up of innovations. Life was tough, and the viable lifetime of individual groups of people may not have been long enough for them to be likely to pass on innovations (either their own ones encountered through contact with other groups).

Software development is often done by small groups that don’t communicate with other groups and regularly die out (well there is a high turn-over, with many of the more experienced people moving on to non-software roles). There are sufficient parallels between hunter gathers and software developers to suggest both were/are kept in a Stone Age for the same reason, lack of a method that enables people to obtain information about innovations and how worthwhile these might be within a given environment.

A huge barrier to the development of better software development practices is the almost complete lack of significant quantities of reliable empirical data that can be used to judge whether a claimed innovation is really worthwhile. Companies rarely make their detailed fault databases and product development history public; who wants to risk negative publicity and lawsuits just so academics have some data to work with.

At the start of this decade, public source code repositories like SourceForge and public software fault repositories like Bugzilla started to spring up. These repositories contain a huge amount of information about the characteristics of the software development process. Questions that can be asked of this data include: what are common patterns of development and which ones result in fewer faults, how does software evolve and how well do the techniques used to manage it work.

Empirical software engineering researchers are now setting up repositories, like Promise, containing the raw data from their analysis of Open Source (and some closed source) projects. By making this raw data available, they are reducing the effort needed by other researchers to investigate their own alternative ideas (I have just started a book on empirical software engineering using the R statistical language that uses examples based on this raw data).

One of the side effects of Open Source development could be the creation of software development practices that have been shown to be better (including showing that some existing practices make things worse). The source of these practices not being what the software developers themselves do or how they do it, but the footsteps they have left behind in the sand.

Readability, an experimental view

Readability is an attribute that source code is often claimed to have, but what is it? While people are happy to use the term they have great difficulty in defining exactly what it is (I will eventually get around discussing my own own views in post). Ray Buse took a very simply approach to answering this question, he asked lots of people (to be exact 120 students) to rate short snippets of code and analysed the results. Like all good researchers he made his data available to others. This posting discusses my thoughts on the expected results and some analysis of the results.

The subjects were first, second, third year undergraduates and postgraduates. I would not expect first year students to know anything and for their results to be essentially random. Over the years, as they gain more experience, I would expect individual views on what constitutes readability to stabilize. The input from friends, teachers, books and web pages might be expected to create some degree of agreement between different students’ view of what constitutes readability. I’m not saying that this common view is correct or bears any relationship to views held by other groups of people, only that there might be some degree of convergence within a group of people studying together.

Readability is not something that students can be expected to have explicitly studied (I’m assuming that it plays an insignificant part in any course marks), so their knowledge of it is implicit. Some students will enjoy writing code and spends lots of time doing it while (many) others will not.

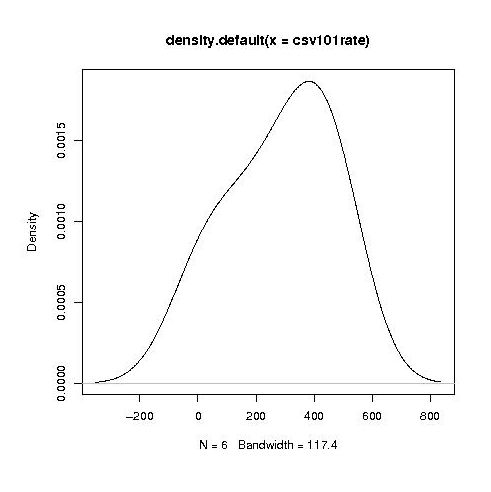

Separating out the data by year the results for first year students look like a normal distribution with a slight bulge on one side (created using plot(density(1_to_5_rating_data)) in R).

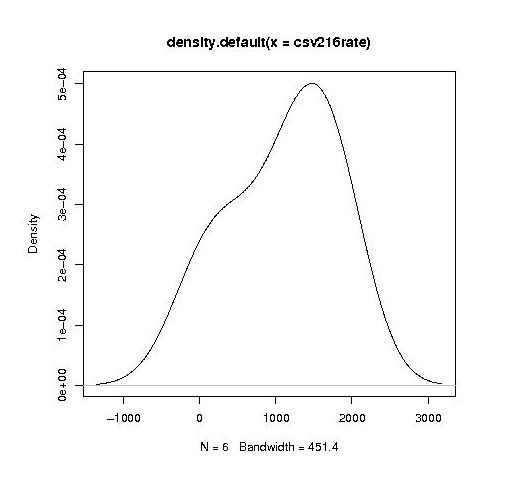

year by year this bulge turns (second year):

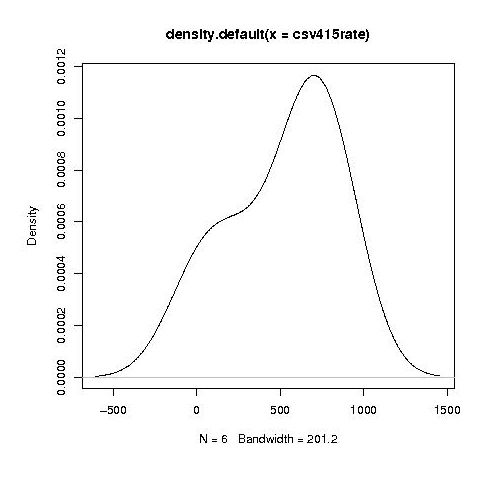

into a hillock (final year):

It is tempting to interpret these results as the majority of students assigning an essentially random rating, with a slight positive bias, for the readability of each snippet, with a growing number of more experienced students assigning less than average rating to some snippets.

Do the student’s view converge to a common opinion on readability? The answers appears to be No. An analysis of the final year data using Fleiss’s Kappa shows that there is virtually no agreement between students ratings. In fact every Interrater Reliability and Agreement function I tried said the same thing. Some cluster analysis might enable me to locate students holding similar views.

In an email exchange with Ray Buse I learned that the postgraduate students had a relatively wide range of computing expertise, so I did not analyse their results.

I wish I had thought of this approach to measuring readability. Its simplicity makes it amenable for use in a wide range of experimental situations. The one change I would make is that I would explicitly create the snippets to have certain properties, rather than randomly extracting them from existing source.

Recent Comments