Archive

Functions reduce the need to remember lots of variables

What, if any, are the benefits of adding bureaucracy to a program by organizing a file’s source code into multiple function/method definitions (rather than a single function)?

Having a single copy of a sequence of statements that need to be executed at multiple points in a program reduces implementation effort, and any updates only need to be made once (reducing coding mistakes by removing the need to correctly make duplicate changes). A function/method is the container for this sequence of statements.

Why break code up into separate functions when each is only called once and only likely to ever be called once?

The benefits claimed from splitting code into functions include: making it easier to understand, test, debug, maintain, reuse, and scale development (i.e., multiple developers working on the same program). Our LLM overlords also make these claims, and hallucinate references to published evidence (after three iterations of pointing out the hallucinated references, I gave up asking for evidence; my experience with asking people is that they usually remember once reading something but cannot remember the source).

Regular readers will not be surprised to learn that there is little or no evidence for any of the claimed benefits. I’m not saying that the benefits don’t exist (I think there are some), simply that there have not been any reliable studies attempting to measure the benefits (pointers to such studies welcome).

Having decided to cluster source code into functions, for whatever reason, are there any organizational rules of thumb worth following?

Rules of thumb commonly involve function length (it’s easy to measure) and desirable semantic characteristics of distinct functions (it’s very hard to measure semantic characteristics).

Claims for there being an optimal function length (i.e., lines of code that minimises coding mistakes) turned out to be driven by a mathematical artifact of the axis used when plotting (miniscule) datasets.

Semantic rules of thumb such as: group by purpose, do one thing, and Single-responsibility principle are open to multiple interpretations that often boil down to personal preferences and experience.

One benefit of using functions that is rarely studied is the restricted visibility of local variables defined within them, i.e., only visible within the function body.

When trying to figure out what code does, readers have to keep track of the information contained in all the variables accessed. Having to track more variables not only increases demands on reader memory, it also increases the opportunities for making mistakes.

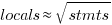

A study of C source found that within a function, the number of local variables is proportional to the square root of the number of statements (code+data). Assuming the proportionality constant is one, a function containing 100 statements might be expected to define 10 local variables. Splitting this function up into, say, four functions containing 25 statements, each is expected to define 5 local variables. The number of local variables that need to be remembered at the same time, when reading a function definition, has halved, although the total number of local variables that need to be remembered when processing those 100 statements has doubled. Some number of global variables and function parameters need to be added to create an overall total for the number of variables.

The plot below shows the number of locals defined in 36,617 C functions containing a given number of statements, the red line is a fitted regression model having the form:  (code+data):

(code+data):

My experience with working with recently self-taught developers, especially very intelligent ones, is that they tend to write monolithic programs, i.e., everything in one function in one file. This minimal bureaucracy approach minimises the friction of a stream of thought development process for adding new code, and changing existing code as the program evolves. Most of these programs are small (i.e., at most a few hundred lines). Assuming that these people continue to code, one of two events teaches them the benefits of function bureaucracy:

- changes to older programs becomes error-prone. This happens because the developer has forgotten details they once knew, e.g., they forget which variables are in use at particular points in the code,

- the size of a program eventually exceeds their ability to remember all of it (very intelligent people can usually remember much larger programs than the rest of us). Coding mistakes occur because they forget which variables are in use at particular points in the code.

Clustering source code within functions

The question of how best to cluster source code into functions is a perennial debate that has been ongoing since functions were first created.

Beginner programmers are told that clustering code into functions is good, for a variety of reasons (none of the claims are backed up by experimental evidence). Structuring code based on clustering the implementation of a single feature is a common recommendation; this rationale can be applied at both the function/method and file/class level.

The idea of an optimal function length (measured in statements) continues to appeal to developers/researchers, but lacks supporting evidence (despite a cottage industry of research papers). The observation that most reported fault appear in short functions is a consequence of most of a program’s code appearing in short functions.

I have had to deal with code that has not been clustered into functions. When microcomputers took off, some businessmen taught themselves to code, wrote software for their line of work and started selling it. If the software was a success, more functionality was needed, and the businessman (never encountered a woman doing this) struggled to keep on top of things. A common theme was a few thousand lines of unstructured code in one function in a single file (keeping everything in one file is also a trait of highly focus developers).

Adding structural bureaucracy (e.g., functions and multiple files) reduced the effort needed to maintain and enhance the code.

The problem with ‘born flat’ source is that the code for unrelated functionality is often intermixed, and global variables are freely used to communicate state. I have seen the same problems in structured function code, but instances are nowhere near as pervasive.

When implementing the same program, do different developers create functions implementing essentially the same functionality?

I am aware of two datasets relating to this question: 1) when implementing the same small specification (average length program 46.3 lines), a surprising number of variants (6,301) are created, 2) an experiment that asked developers to reintroduce functions into ‘flattened’ code.

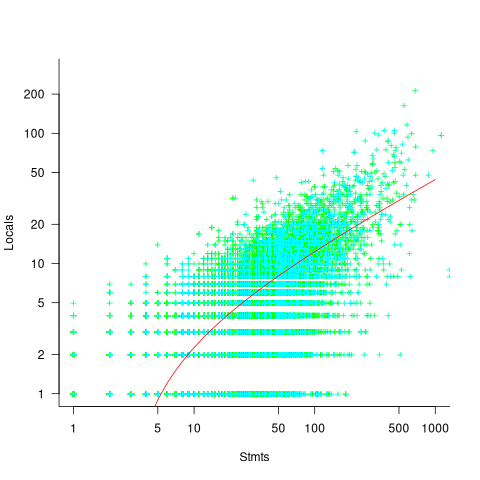

The experiment (Alexey Braver’s MSc thesis) took an existing Python program, ‘flattened’ it by inlining functions (parameters were replaced by the corresponding call arguments), and asked subjects to “… partition it into functions in order to achieve what you consider to be a good design.”

The 23 rows in the plot below show the start/end (green/brown delimited by blue lines) of each function created by the 23 subjects; red shows code not within a function, and right axis is percentage of each subjects’ code contained in functions. Blue line shows original (currently plotted incorrectly; patched original code+data):

There are many possible reasons for the high level of agreement between subjects, including: 1) the particular example chosen, 2) the code was already well-structured, 3) subjects were explicitly asked to create functions, 4) the iterative process of discovering code that needs to be written did not occur, 5) no incentive to leave existing working code as-is.

Given that most source has a short and lonely existence, is too much time being spent bike-shedding function contents?

Given how often lower level design time happens at code implementation time, perhaps discussion of function contents ought to be viewed as more about thinking how things fit together and interact, than about each function in isolation.

Analyzing each function in isolation can create perverse incentives.

Code bureaucracy can reduce the demand for cognitive resources

A few weeks ago I discussed why I thought that research code was likely to remain a tangled mess of spaghetti code.

Everybody’s writing, independent of work-place, starts out as a tangled mess of spaghetti code; some people learn to write code in a less cognitively demanding style, and others stick with stream-of-conscious writing.

Why is writing a tangled mess of spaghetti code (sometimes) not cost-effective, and what are the benefits in making a personal investment in learning to write code in another style?

Perhaps the defining characteristic of a tangled mess of spaghetti code is that everything appears to depend on everything else, consequently: working out the impact of a change to some sequence of code requires an understanding of all the other code (to find out what really does depend on what).

When first starting to learn to program, the people who can hold the necessary information on increasing amounts of code in their head are the ones who manage to create running (of sorts) programs; they have the ‘knack’.

The limiting factor for an individual’s software development is the amount of code they can fit in their head, while going about their daily activities. The metric ‘code that can be fitted in a person’s head’ is an easy concept to grasp, but its definition in terms of the cognitive capacity to store, combine and analyse information in long term memory and the episodic memory of earlier work is difficult to pin down. The reason people live a monks existence when single-handedly writing 30-100 KLOC spaghetti programs (the C preprocessor Richard Stallman wrote for gcc is a good example), is that they have to shut out all other calls on their cognitive resources.

Given time, and the opportunity for some trial and error, a newbie programmer who does not shut their non-coding life down can create, say, a 1,000+ LOC program. Things work well enough, what is the problem?

The problems start when the author stops working on the code for long enough for them to forget important dependencies; making changes to the code now causes things to mysteriously stop working. Our not so newbie programmer now has to go through the frustrating and ego-denting experience of reacquainting themselves with how the code fits together.

There are ways of organizing code such that less cognitive resources are needed to work on it, compared to a tangled mess of spaghetti code. Every professional developer has a view on how best to organize code, what they all have in common is a lack of evidence for their performance relative to other possibilities.

Code bureaucracy does not sound like something that anybody would want to add to their program, but it succinctly describes the underlying principle of all the effective organizational techniques for code.

Bureaucracy compartmentalizes code and arranges the compartments into some form of hierarchy. The hoped-for benefit of this bureaucracy is a reduction in the cognitive resources needed to work on the code. Compartmentalization can significantly reduce the amount of a program’s code that a developer needs to keep in their head, when working on some functionality. It is possible for code to be compartmentalized in a way that requires even more cognitive resources to implement some functionality than without the bureaucracy. Figuring out the appropriate bureaucracy is a skill that comes with practice and knowledge of the application domain.

Once a newbie programmer is up and running (i.e., creating programs that work well enough), they often view the code bureaucracy approach as something that does not apply to them (and if they rarely write code, it might not apply to them). Stream of conscious coding works for them, why change?

I have seen people switch to using code bureaucracy for two reasons:

- peer pressure. They join a group of developers who develop using some form of code bureaucracy, and their boss tells them that this is the way they have to work. In this case there is the added benefit of being able to discuss things with others,

- multiple experiences of the costs of failure. The costs may come from the failure to scale a program beyond some amount of code, or having to keep investing in learning how previously written programs work.

Code bureaucracy has many layers. At the bottom there is splitting code up into functions/methods, then at the next layer related functions are collected together into files/classes, then the layers become less generally agreed upon (different directories are often involved).

One of the benefits of bureaucracy, from the management perspective, is interchangeability of people. Why would somebody make an investment in code bureaucracy if they were not the one likely to reap the benefit?

A claimed benefit of code bureaucracy is ease of wholesale replacement of one compartment by a new one. My experience, along with the little data I have seen, suggests that major replacement is rare, i.e., this is not a commonly accrued benefit.

Another claimed benefit of code bureaucracy is that it makes programs easier to test. What does ‘easier to test’ mean? I have seen reliable programs built from spaghetti code, and unreliable programs packed with code bureaucracy. A more accurate claim is that it can be unexpectedly costly to test programs built from spaghetti code after they have been changed (because of the greater likelihood of the changes having unexpected consequences). A surprising number of programs built from spaghetti code continue to be used in unmodified form for years, because nobody dare risk the cost of checking that they continue to work as expected after a modification

Christmas books for 2016

Here are couple of suggestions for books this Christmas. As always, the timing of the books I suggest is based on when they reach the top of the books-to-read pile, not when they were published.

“The Utopia of rules” by David Graeber (who also wrote the highly recommended “Debt : The First 5000 Years”). Full of eye opening insights into bureaucracy, how the ‘free’ world’s state apparatus came to have its current form and how various cultures have reacted to the imposition of bureaucratic rules. Very readable.

“How Apollo Flew to the Moon” by W. David Woods. This is a technical nuts-and-bolts story of how Apollo got to the moon and back. It is the best book I have every read on the subject, and as a teenager during the Apollo missions I read all the books I could find.

This year’s blog find was Scott Adams’ blog (yes, he of Dilbert fame). I had been watching Donald Trump’s rise for about a year and understood that almost everything he said was designed to appeal to a specific audience and the fact that it sounded crazy to those not in the target audience was irrelevant. I found Scott’s blog contained lots of interesting insights of the goings on in the US election; the insights into why Trump was saying the things he said have proved to be spot on.

For those of you interested in theoretical physics I ought to mention Backreaction (regular updates, primarily about gravity related topics) and Of Particular Significance (sporadic updates and primarily about particle physics)

R needs some bureaucracy

Writing a program in R is almost bureaucracy free: variables don’t need to be declared, the language does a reasonable job of guessing the type a value might need to be automatically be converted to, there is no need to create a function having a special name that gets called at program startup, the commonly used library functions are ready and waiting to be called and so on.

Not having a bureaucracy is all well and good when programs are small or short lived. Large programs need a bureaucracy to provide compartmentalization (most changes to X need to be prevented from having an impact outside of X, doing this without appropriate language support eventually burns out anybody juggling it all in their head) and long lived programs need a bureaucracy to provide version control (because R and its third-party libraries change over time).

Automatically installing a package from CRAN always fetches the latest version. This is all well and good during initial program development. But will the code still work in six months time? Perhaps the author of one of the packages used in the program submits a new version of that package to CRAN and this new version behaves slightly differently, breaking the previously working program. Once the problem is located the developer has either to update their code or manually install the older version of the package. Life would be easier if it was possible to specify the required package version number in the call to the library function.

Discovering that my code depends on a particular version of a CRAN package is an irritation. Discovering that two packages I use each have a dependency on different versions of the same package is a nightmare. Having to square this circle is known in the Microsoft Windows world as DLL hell.

There is a new paper out proposing a system of dependency versioning for package management. The author proposes adding a version parameter to the library function, plus lots of other potentially useful functionality.

Apart from changing the behavior of functions a program calls, what else can a package author do to break developer code? They can create new functions and variables. The following is some code that worked last week:

library("foo") # The function get_question is in this package library("bar") # The function give_answer_42 is in this package (the_question=get_question()) give_answer_42(the_question) |

between last week and today the author of package foo (or perhaps the author of one of the packages that foo has a dependency on) has added support for the function solve_problem_42 and it is this function that will now get called by this code (unless the ordering of the calls to library are switched). What developers need to be able to write is:

library("foo", import=c("the_question")) # The function get_question is in this package library("bar", import=c("give_answer_42")) # The function give_answer_42 is in this package (the_question=get_question()) give_answer_42(the_question) |

to stop this happening.

The import parameter enables developers to introduce some compartmentalization into my programs. Yes, R does have namespace management for packages, and I’m pleased to see that its use will be mandatory in R version 3.0.0, but this does not protect programs from functions the package author intends to export.

I’m not sure whether this import suggestion will connect with R users (who look very laissez faire to me), but I get very twitchy watching a call to library go off and install lots of other stuff and generate warnings about this and that being masked.

Recent Comments