Archive

Relative sizes of computer companies

How large are computer companies, compared to each other and to companies in other business areas?

Stock market valuation is a one measure of company size, another is a company’s total revenue (i.e., total amount of money brought in by a company’s operations). A company can have a huge revenue, but a low stock market valuation because it makes little profit (because it has to spend an almost equally huge amount to produce that income) and things are not expected to change.

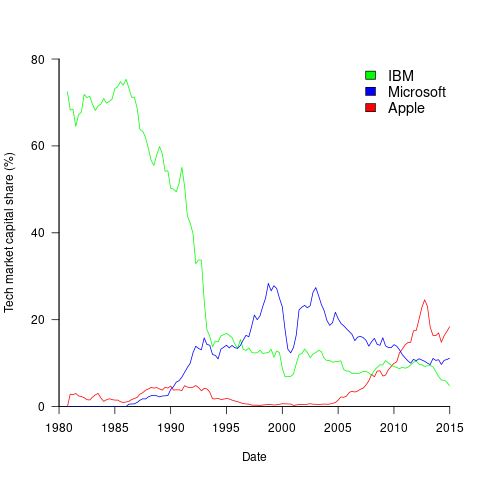

The plot below shows the stock market valuation of IBM/Microsoft/Apple, over time, as a percentage of the valuation of tech companies on the US stock exchange (code+data on Github):

The growth of major tech companies, from the mid-1980s caused IBM’s dominant position to dramatically decline, while first Microsoft, and then Apple, grew to have more dominant market positions.

Is IBM’s decline in market valuation mirrored by a decline in its revenue?

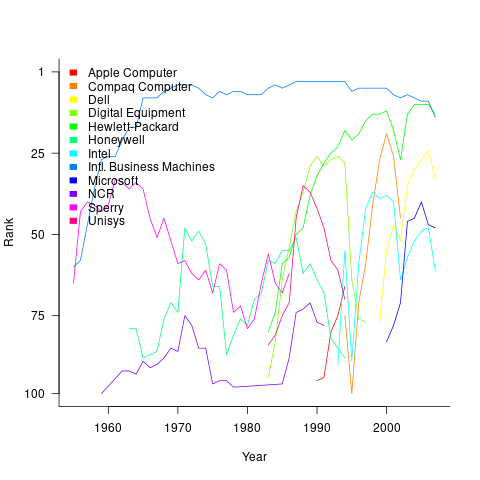

The Fortune 500 was an annual list of the top 500 largest US companies, by total revenue (it’s now a global company list), and the lists from 1955 to 2012 are available via the Wayback Machine. Which of the 1,959 companies appearing in the top 500 lists should be classified as computer companies? Lacking a list of business classification codes for US companies, I asked Chat GPT-4 to classify these companies (responses, which include a summary of the business area). GPT-4 sometimes classified companies that were/are heavy users of computers, or suppliers of electronic components as a computer company. For instance, I consider Verizon Communications to be a communication company.

The plot below shows the ranking of those computer companies appearing within the top 100 of the Fortune 500, after removing companies not primarily in the computer business (code+data):

IBM is the uppermost blue line, ranking in the top-10 since the late-1960s. Microsoft and Apple are slowly working their way up from much lower ranks.

These contrasting plots illustrate the fact that while IBM continued to a large company by revenue, its low profitability (and major losses) and the perceived lack of a viable route to sustainable profitability resulted in it having a lower stock market valuation than computer companies with much lower revenues.

What language was an executable originally written in?

Apple have recently added an unusual requirement to the iPhone developer agreement “Applications must be originally written in Objective-C, C, C++, or JavaScript …”. As has been pointed out elsewhere the real purpose is stop third party’s from acquiring any control over application development on Apple’s products; the banning of other languages is presumably regarded as acceptable collateral damage.

Is it possible to tell by analyzing an executable what language it was originally written in?

There are two ways in which executables contain source language ‘signatures’. Detecting these signatures requires knowledge of specific compiler behavior, i.e., a database of information about the behavior of compilers capable of creating the executables is needed.

Runtime library. Most compilers make use of a language specific runtime library, rather than generating inline code for some kinds of functionality. For instance, setjmp/longjmp in C and vtables in C++.

The presence of a known C runtime library does not guarantee that the application was originally written in C; it could have been written in Java and converted to C source.

The absence of a known C runtime library could mean that the source was compiled by a C compiler using a runtime system unknown to the analyzer.

The presence of a known Java, for instance, runtime library would suggest that the original source contained some Java. This kind of analysis would obviously require that the runtime library database not restrict itself to the ‘C’ languages.

Compiler behavior patterns. There is usually more than one way in which a source language construct can be translated to machine code and a compiler has to pick one of them. The perfect optimizing compiler would always make the optimal choice, but real compilers follow a fixed pattern of code generation for at least some language constructs (e.g., initialization of registers on function entry).

The presence of known code patterns in an executable is evidence that a particular compiler has been used; how much depends on the likelihood it could have been generated by other means and how many other patterns suggest the same compiler. In the case of the GNU Compiler Collection the source language might also be Fortran, Java or Ada; I don’t know enough about the behavior of GCC to provide an informed estimate of whether it is possible to recognize the source language from the translated form of constructs shared by several languages, I suspect not.

The fact that an executable can be decompiled to C is not a guarantee that it was originally written in C.

Some languages support source language constructs whose corresponding machine code is unlikely to ever be generated by source from another language. The Fortran computed goto allows constructs to be written that have no equivalent in the other languages supported by GCC (none of them allow statement labels appearing in a multi-way jump to appear before the jump test):

10 I=I+1 20 J=J+1 goto (10, 20, 30, 40) J 30 I=I+3 40 I=I*2 |

The presence of a compiled form of this kind of construct in the executable would be very suggestive of Fortran source.

Apple are famously paranoid and control freakery. It will be very interesting to see what level of compliance checking they decide to perform on executables submitted to the App Store.

On another note: What does “originally written” mean? For instance, many of the mathematical functions (e.g., sine, log, gamma, etc) contained in R were originally written in Fortran and translated to C for use in R; this C source is what is now maintained. Does this historical implementation decision mean that R cannot be legally ported to the iPhone?

Recent Comments