Archive

A safety-critical certification of the Linux kernel

This week there was an announcement on the system-safety mailing list that the Red Hat In-Vehicle Operating System (a version of the Linux kernel, plus a few subsystems) had been certified as being “… capable for use in ASIL B applications, …”. The Automotive Safety Integrity Levels (ASIL A is the lowest level, with D the highest; an example of ASIL B is controlling brake lights) are defined by ISO 26262, an international standard for functional safety of electrical and/or electronic systems installed in production road vehicles.

Given all I had heard about the problems that needed to be solved to get a safety certification for something as large and complicated as the Linux kernel, I wanted to know more about how Red Hat had achieved this certification.

The traditional, idealised, approach to certifying software is to check that all requirements are documented and traceable to the design, source code, tests, and test results. This information can be used to ensure that every requirement is implemented and produces the intended behavior, and that no undocumented functionality has been implemented.

When this approach is not practical (because of onerous time/cost), a potential get out of jail card is to use a Rigorous Development Process. Certification friendly development processes appear to revolve around lots of bureaucracy and following established buzzword techniques. The only development processes that have sometimes produced very reliable software all involve spending lots of time/money.

The major problems with certifying Linux are the apparent lack of specification/requirements documents, and a development process that does not claim to be rigorous.

The Red Hat approach is to treat the Linux man pages as the specification, extract the requirements from these pages, and then write the appropriate tests. Traceability looks like it is currently on the to-do list.

I have spent a lot of time working to understand specifications and their requirements; first with the C Standard and then with the Microsoft Server Protocols. This is the first time I have encountered man pages being used in a formal setting (sometimes they are used as one of the inputs to a reimplementation of a library).

Very little Open source software has a written specification in the traditional sense of a document cited in a contract that the vendor agrees to implement. Manuals, READMEs and help pages are not written in the formal style of a specification. A common refrain is that the source code is the specification. However, source is a specification of what the program does, it is not a specification of what the program is supposed to do.

The very nature of the Agile development process demands that there not be a complete specification. It’s possible that user stories could be treated as requirements.

There is an ISO Standard with Linux in its title: the Linux Base Standard. The goal of this Standard “… is to develop and promote a set of open standards that will increase compatibility among Linux distributions and enable software applications to run on any compliant system …”, i.e., it is not a specification of an OS kernel.

POSIX is a specification of the behavior of an OS (kernel functionality is specified by POSIX.1, .2 is shell and utilities, plus other .x documents). It’s many years since I tracked POSIX/Linux compliance, which was best described as “highly compatible”. Both Grok3 and ChatGPT o4 agree that “highly compatible” is still true, and list some known incompatibilities.

While they are not written in the form of a specification, the Linux man pages do have a consistent structure and are intended to be up-to-date. A person with a background of working with Linux kernels could probably extract meaningful requirements.

How many requirements are needed to cover the behavior of the Linux kernel?

On my computer running a 6.8.0-51 kernel, the /usr/include/linux directory contains 587 header files. Based on an analysis from 20 years ago (table 1897.1), most of these headers only declare macros and types (e.g., memory layout), not function declarations. The total number of function declarations in these headers is probably in the low thousands. POSIX (2008 version) defines 1,177 functions, but the number of system calls is probably around 300-400. Android implements 821 of these functions, of which 343 are system call related.

Let’s assume 2,000 functions. Some of these functions have an argument that specifies one or more optional values, each specifying a different sub-behavior. How many different sub-behaviors are there? If we assume that each kind of behavior is specified using a C macro, then Table 1897.1 suggests there might be around 10k C macros defined in these headers.

With positive/negative tests for each case, in round numbers we get (ignoring explicit testing of the values of struct members):  test files.

test files.

This calculation does not take into account combinations of options. I’m assuming that each test file will loop through various combinations of its kind of sub-behavior.

The 1990 C compiler validation suite contained around 1k tests. Thirty-five years later, 24k test files for a large OS feels low, but then combination testing should multiply the number of actual tests by at least an order of magnitude.

What is this hand-wavy analysis missing?

I suspect that the kernel is built with most of the optional functionality conditionally compiled out. This could significantly reduce the number of api functions and the supported options.

I have not taken into account any testing of the user-visible kernel data structures (because I don’t have any occurrence data).

Comments from readers with experience in testing OSes most welcome.

Another source of Linux specific information is the Linux Kernel documentation project. I don’t have any experience using this documentation, but the API documentation is very minimalist (automatically extracted from the source; the Assessment report lists this document as [D124], but never references it in the text).

Readers familiar with safety standards will be asking about the context in which this certification applies. Safety functions are not generic; they are specific to a safety-related system, i.e., software+hardware. This particular certification is for a Safety Element out of Context (SEooC), where “out of context” here means without the context of a system or knowledge of the safety goals. SEooC supports a bottom up approach to safety development, i.e., Safety Elements can be combined, along with the appropriate analysis and testing, to create a safety-related system.

This certification is the first of what I think will be many certifications of Linux, some at more rigorous safety levels.

APIs can, for the time being, be copyrighted

There was an interesting turn of events in the Oracle vs. Google Java API lawsuit last friday. The original trial judge had ruled that an API are not copyrightable; last week the US federal Court of appeals reversed this decision, APIs are copyrightable. This legal battle is not over and the ruling can flip and flop its way up to the US supreme court, and not being a lawyer I’m happy to leave the legal discussion to others. Let’s assume that Oracle eventually win their Java API copyright claim, what does that mean for computer language usage and software developers?

If Oracle’s API copyright claim is upheld then they are potentially in line for a huge payout (Google might get to wiggle out of paying much via a fair use justification). I’m sure that some people will claim that this ‘win’ will kill off Java, even if this is true (I don’t think it is), what do the suits care? Give me a billion dollars and I will happily support the removal of any computer language from planet Earth.

In the early days of Android Google needed Java compatibility more than Java needed anything to do with Android. Now Android has such a commanding market share Google does not need to worry so much about Java compatibility. If Oracle had any interest in the future of Java they would be worried that this court case could result in Google switching the Android ecosystem to using a slightly incompatible Java-like language. In practice this court case is the only real opportunity for Oracle to make serious money from their Java intellectual property and they are not that excited about a steady stream of peanuts from future goings on.

What does Oracle winning the API copyright claim mean for developers?

If Google do launch a Java-like language then Java’s “write once run anywhere” mantra will be less true than it currently is (by avoiding a few traps and not straying too far from the well trodden path Java developers can create programs that are remarkable portable). In its market niche there is no other language that comes close to providing the kind of portability that Java offers, so existing users will be annoyed at having to worry about one more portability issue but are unlikely to jump ship.

The much more interesting question is the impact an Oracle win has on other companies producing products that include an API; they now have something to wave at competitors who have API-alike (I just made that word up) products. Any developer using an API that has its very own copyright discussion thread is likely to become a bit twitchy. The general result will be a cloud of uncertainty over some existing APIs from some providers.

Anybody introducing a new API will have to answer the ‘copyright’ question: “Do you claim copyright on your API?” In practice a very very small percentage of APIs ever get copied/cloned, because most fail or the competition comes up with what they think is a better API.

Would I care if a company claims copyright on its API and says it will sue anybody who copies/clones it? Obviously I have to use that API if it is the only way to get a job done, but what if I had a choice between it and a non-copyrighted API? I don’t think the question of copyright would be an issue for me, but I would be concerned if any company was being overly legalistic; do I really want to deal with a company more interested in legal matters than supporting developers? I think not.

Changes in the API/non-API method call ratio with program size

Amount of code is the fundamental metric of software engineering. How do things change as the amount of code changes and often just as interestingly what does not change with code size?

Most languages include some kind of base library functionality. Languages such as Java and C++ not only include a very large library but also a huge, widely used, collection of third-party libraries.

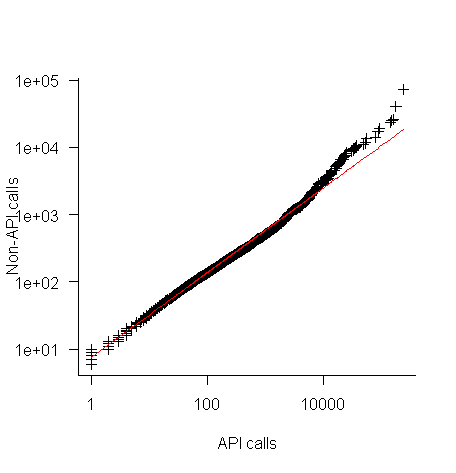

Let’s count every method call in lots of Java programs and for each program divide these calls into two groups, calls to methods in well-known libraries (call these the API methods) and all other method calls (i.e., calls to methods written by the developers who wrote each of the programs measured; call these the non-API methods).

I would expect the ratio of API to non-API method calls to be independent of program size.

Yes, the number of possible different API calls is fixed while the number of possible non-API calls increases with program size, but I don’t see why a changing ratio of unique calls should change the ratio of total calls.

Yes, larger programs are likely to contain more architectural stuff whose code is more likely to contain calls to non-API methods, but the percentage of architectural code is very small and unlikely to have much impact on the overall numbers.

The authors of the paper: Large-scale, AST-based API-usage analysis of open-source Java projects made their data available and so I got to check out my thinking 🙂

The plot below shows everything going to plan until around 10,000 method calls (about 50,000 lines of code). Why that sudden kink in the line (code and data)?

One possibility is that once a program gets to a size of around 50,000 lines the developers decide to invest in one or more wrapper packages which create a purpose built interface to an API (programs often have their own requirements and needs that existing an existing API interface does not quite meet); this would cause API calls to decrease and non-API calls to increase. If this pattern of usage occurred there would be a permanent change in the API/non-API ratio, and in practice the ratio change appears to be temporary.

I’m a bit stumped by this behavior. Suggestions on possible mechanisms welcome.

I wish I had the time to investigate, but I have a book to finish.

Apps in Space Hackathon

I went along to the Satellite Applications hackathon last weekend. As a teenager I was very much into space flight and with this event being only 30 miles away how could I not attend. Around 25 or so hackers turned up, supported by seven or so knowledgeable and motivated people from the organizers/sponsors. Excellent food+drink, including sending out for Indian/Chinese for dinner. The one important item in short supply was example data to experiment with; the organizers are aware of this and plan to have a lot more data available at the next event.

The rationale for the event is to encourage the creation of business activities in the UK around the increasing amount of data beamed to Earth from satellites. At the moment a satellite image costs something like £100 if its in the back catalog and £10,000 if you want them to take one just for you; the price of images in the back catalog is about to plummet (new satellites coming on stream) and a company is being set up to act as a one stop shop+good user interface for pics (at the moment customers have to talk to a variety of suppliers to find see what’s available). I was excited to hear that I could have my own satellite launched for £100,000, the catch being that they are a bit more expensive to build.

Making use of satellite data requires other data plus support software. Many of the projects people decided to work on needed access to mapping data, e.g., which road is closest to this latitude/longitude. Open Streetmap is the obvious source of mapping data, the UK’s Ordinance Survey have also made some data freely available for public/commercial use. The current problem with this data is the lack of support libraries designed to handle satellite related queries (e.g., return nearest road, town, etc), the existing APIs are good for creating mapping images and dealing with routing.

Support for very large images is one area where existing tools are going to need an upgrade; by very large I mean single image files measured in gigabytes. I did not manage to view any gigabyte image files on my laptop (with 4G of ram), even after going for a coffee and sitting talking to somebody waiting for it to cool before drinking it, still a black rectangle. If the price of satellite images plummets and are easy to buy online, then I can imagine them becoming a discretionary item that people buy for a bit of fun and will then want to view using the devices they already own; telling them that this is not sensible is the wrong answer, the customer is always right and it has to be made to work.

One area where there is good software tool support is working out where satellites will appear in the sky; this is really an astronomical application and there are lots of astronomical tools out there. The Python crowd will be happy to know that scientific-grade astronomy routines are available in Pyephem.

For the most part the hacks created are bullet points of ideas and things to do. The team working on calculating the satellite beam likely to have the strongest signal at a given point on the Earth’s surface made a lot more progress than anybody else. This is because they had an existing Python library to use and ‘only’ needed to apply the trigonometry that we all learn in school.

Some suggestions for the organizers:

- put lightening talks on existing technologies and some of their uses on the agenda (the brief presentation given on SAR was eye opening),

- make some good example data public, i.e., downloadable for all to use. This is the only way to get lots of library support written,

- create cut-down datasets that are usable on laptops. At a Hackathon people can only productively use what they know well and requiring them to use something unfamiliar, such as a virtual machine, is a major road block,

- allow external users to take part, why limit your potential customer base to what can be fitted into a medium size room?

Recent Comments