Why does Coverity restrict who can see its tool output?

Coverity generate a lot of publicity from their contract (started under a contract with the US Department of Homeland Security, don’t know if things have changed) to scan large quantities of open source software with their static analysis tools and a while back I decided to have a look at the warning messages they produce. I was surprised to find that access to the output required singing a non-disclosure agreement, this has subsequently been changed to agreeing to a click-through license for the basic features and signing a NDA for access to advanced features. Were Coverity limiting access because they did not want competitors learning about new suspicious constructs to flag, or because they did not want potential customers seeing what a poor job their tool did?

The claim that access “… for most projects is permitted only to members of the scanned project, partially in order to ensure that potential security issues may be resolved before the public sees them.” does not really hold much water. Anybody interested in finding security problems in code could probably find hacked versions of various commercial static analysis tools to download. The SAMATE – Software Assurance Metrics And Tool Evaluation project runs yearly evaluations of static analysis tools and makes the results publicly available.

A recent blog post by Andy Chou, Coverity’s CTO, added weight to the argument that their Scan tool is rather run-of-the-mill. The post discussed a new check that had recently been added flagging occurrences of memcmp, and related standard library functions, that were being tested for equality (or inequality) with specific integer constants (these functions are defined to return a negative or positive value or 0, and while many implementations always return the negative value -1 and the positive value 1 a developer should always test for the property of being negative/positive and not specific values that have that property). Standards define library functions to have a wide variety of different properties, and tools that check for correct application of these properties have been available for over 15 years.

My experience of developer response, when told that some library function is required to return a negative value and some implementation might not return -1, is that they regard any implementation not returning -1 as being ‘faulty’ since all implementations in their experience return -1. I imagine that library implementors are aware of this expectation and try to meet it. However, optimizing compilers often try to automatically inline calls to memcpy and related copy/compare functions and will want to take advantage of the freedom to return any negative/positive value if it means not having to perform a branch test (a big performance killer on most modern processors).

Undefined behavior can travel back in time

The committee that produced the C Standard tried to keep things simple and sometimes made very short general statements that relied on compiler writers interpreting them in a ‘reasonable’ way. One example of this reliance on ‘reasonable’ behavior is the definition of undefined behavior; “… erroneous program construct or of erroneous data, for which this International Standard imposes no requirements”. The wording in the Standard permits a compiler to process the following program:

int main(int argc, char **argv) { // lots of code that prints out useful information 1 / 0; // divide by zero, undefined behavior } |

to produce an executable that prints out “yah boo sucks”. Such behavior would probably be surprising to the developer who expected the code printing the useful information to be executed before the divide by zero was encountered. The phrase quality of implementation is heard a lot in committee discussions of this kind of topic, but this phrase does not appear in any official document.

A modern compiler is essentially a sophisticated domain specific data miner that happens to produce machine code as output and compiler writers are constantly looking for ways to use the information extracted to minimise the code they generate (minimal number of instructions or minimal amount of runtime). The following code is from the Linux kernel and its authors were surprised to find that the “division by zero” messages did not appear when arg2 was 0, in fact the entire if-statement did not appear in the generated code; based on my earlier example you can probably guess what the compiler has done:

if (arg2 == 0) ereport(ERROR, (errcode(ERRCODE_DIVISION_BY_ZERO), errmsg("division by zero"))); /* No overflow is possible */ PG_RETURN_INT32((int32)arg1 / arg2); |

Yes, it figured out that when arg2 == 0 the divide in the call to PG_RETURN_INT32 results in undefined behavior and took the decision that the actual undefined behavior in this instance would not include making the call to ereport which in turn made the if-statement redundant (smaller+faster code, way to go!)

There is/was a bug in Linux because of this compiler behavior. The finger of blame could be pointed at:

- the developers for not specifying that the function

ereportdoes not return (this would enable the compiler to deduce that there is no undefined behavior because the divide is never execute whenarg2 == 0), - the C Standard committee for not specifying a timeline for undefined behavior, e.g., program behavior does not become undefined until the statement containing the offending construct is encountered during program execution,

- the compiler writers for not being ‘reasonable’.

In the coming years more and more developers are likely to encounter this kind of unexpected behavior in their programs as compilers do more and more data mining and are pushed to improve performance. Other examples of this kind of behavior are given in the paper Undefined Behavior: Who Moved My Code?

What might be done to reduce the economic cost of the fallout from this developer ignorance/standard wording/compiler behavior interaction? Possibilities include:

- developer education: few developers are aware that a statement containing undefined behavior can have an impact on the execution of code that occurs before that statement is executed,

- change the wording in the Standard: for many cases there is no reason why the undefined behavior be allowed to reach back in time to before when the statement executing it is executed; this does not mean that any program output is guaranteed to occur, e.g., the host OS might delete any pending output when a divide by zero exception occurs.

- paying gcc/llvm developers to do front end stuff: nearly all gcc funding is to do code generation work (I don’t know anything about llvm funding) and if the US Department of Homeland security are interested in software security they should fund related front end work in gcc and llvm (e.g., providing developers with information about suspicious usage in the code being compiled; the existing

-Wallis a start).

Ternary radix will have to wait for photonic computers

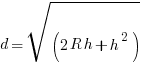

Computer cpu economics suggest that a ternary radix representation rather than binary should be used for representing integer values. The economic cost of a cpu is is roughly proportional to  , where

, where  is the integer radix and

is the integer radix and  is the width, in bits, of the basic integer type (for simplicity I’m assuming there is only one and that the bus width has the same value); the maximum value that can be represented is

is the width, in bits, of the basic integer type (for simplicity I’m assuming there is only one and that the bus width has the same value); the maximum value that can be represented is  .

.

If we fix the maximum representable value  and ask which value of

and ask which value of  minimises

minimises  , then we need to differentiate

, then we need to differentiate  w.r.t.

w.r.t.  , giving

, giving  and this equals 0 when

and this equals 0 when  (the closest integer to

(the closest integer to  is 3).

is 3).

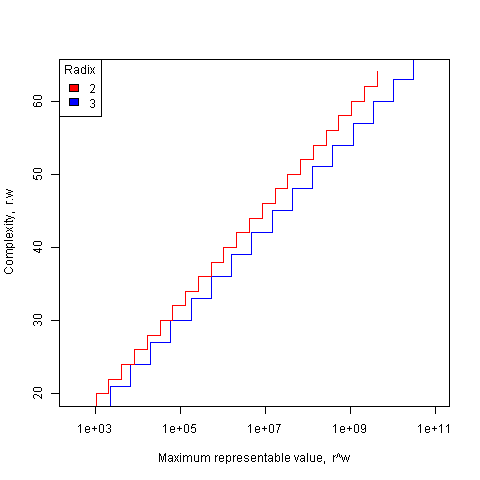

The following plot shows the maximum representable value (right point of horizontal line) that can be achieved for a given ‘cost’ when the radix is 2 and 3.

The reason binary is used in practice is purely to do with the characteristics of power consumption in electronic switching circuits (originally vacuum tube and then transistor based). Electrical power is proportional to voltage times current and a binary circuit can be implemented by switching between states where either the voltage or the current is very small, in either of these two states the power consumption is very low; it is only during the very short transition period switching between them, when the voltage and current have intermediate values, that the power consumed is relatively high. A 3-state switch would need a voltage/current combination denoting a state other than 0/1, and any such combination would consume non-trivial amounts of power (tri-state devices are used in some situations).

I have little idea about the complications of storing ternary values in memory systems, but I guess there will be complications.

In the 1960’s the Setun computer used a ternary radix and there has been the odd experimental systems since.

Are there any kinds of switching circuit whose use is not primarily dictated by device power characteristics and hence might be used to support a ternary radix? One possibility is a light based cpu (i.e., using photons rather than electrons), using polarization to specify state has been proposed. What about storage? Using Josephson junctions could provide the high speed and low power consumption required (we just need somebody to discover a room temperature superconductor).

The technology needed to build a practical cpu using a ternary radix appears to be some years in the future.

What about all the existing code containing a myriad of dependencies on the characteristics of two’s complement integer representation? If a photonic cpu became available that was ten times faster than existing cpus, or consumed 10 times less power or some combination thereof, then I’m sure here would be plenty of economic incentive to get software running on it. The problem is that 10 times better cpus are unlikely to just turn up, they will probably need to be developed in steps and the economics of progressing from step to step don’t look good.

While our civilization is likely to continue on down the binary rabbit hole, another one may have started down, or switched to, the ternary hole. I hope the SETI people are not to blinkered by the binary view of the universe.

Impact of hardware characteristics on detectable fault behavior

Preface. This is the first of what I hope will be many posts analysing experimental data, that will eventually end up in my empirical software engineering with R book (this experiment was chosen because it happens to be the one I am currently working on; having just switched to using Asciidoc I have a backlog of editing to do on previously written analysis, also I have to figure out a way to fix [bracketed words]).

Don’t worry if you don’t know anything about the statistics used. I am aiming to provide information to meet the needs of two audiences (whether or not I fail on both counts remains to be seen):

- Those who want to some idea of what facts are known about a particular software engineering topic. Hopefully reading the introduction+conclusion will enable these readers to form an opinion about the current state of knowledge (taking my statistical analysis on trust).

- Those who are looking for ideas that can be used to analyse a problem they are trying to solve. Hopefully, somewhere among my many analyses will be something that looks like it could be applied to the reader’s problem and motivates them to go off and learn something about the statistics (if they are not already familiar with it; once written the book will obviously help out here).

Forward. The following analysis produces a negative result, something that happens a lot in experiments in all fields of research. It has been included to illustrate the importance of checking the statistical power of an experiment, i.e., how likely the experiment will detect an effect if one is present; it is very easy to fall into the trap of thinking that because lots of tests were done any effect that exists will be detected.

The authors ran an interesting experiment which as far as I know is the only published empirical analysis of intermittent software faults (please let me know if you are aware of other work) and made some mistakes in their statistical analysis. I have made plenty of mistakes in experiments I have run, some of which have found there way into the published write up. The key attribute of an experimentalist is to learn and move on.

A fault does not always noticeably change the behavior of a program when it is executed, apparently correct program execution can occur in the presence of serious faults.

A study by Syed, Robinson and Williams <book Syed_10> investigated how the number of noticeable failures caused by known faults in Mozilla’s Firefox browser varied with processor speed, system memory, hard disc size and system load. A total of 11 known faults causing intermittent failure were selected and nine different hardware configurations were selected. The conditions required to exhibit each fault were replicated and Firefox was executed 10 times for each of hardware configuration, counting the number of noticeable program failures; the seven faults and nine hardware configurations listed in the table below generated a total of 10*7*9 = 630 different executions (four faults either always or never resulted in an observed failure during the 10 runs).

Data

The following table contains the observed number of failures of Firefox for the given fault number when run on the specified hardware configuration.

| Mhz-Mb-Gb | 124750 | 380417 | 410075 | 396863 | 494116 | 264562 | 332330 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

667-128-2.5 |

4 |

10 |

6 |

5 |

2 |

3 |

5 |

|

667-256-10 |

4 |

8 |

8 |

6 |

4 |

3 |

8 |

|

667-1000-2.5 |

4 |

7 |

3 |

4 |

3 |

1 |

8 |

|

1000-128-10 |

3 |

10 |

3 |

6 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

|

1000-256-2.5 |

3 |

9 |

0 |

6 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

|

1000-1000-10 |

2 |

9 |

4 |

5 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

|

2000-128-2.5 |

0 |

10 |

5 |

6 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

2000-256-10 |

2 |

8 |

5 |

7 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

2000-1000-10 |

1 |

7 |

3 |

5 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

Predictions made in advance

There is no prior theory suggesting how the selected hardware characteristics might influence the outcome from this experiment. The analysis is based on searching for a pattern in the results and so the significance level needs to be adjusted to take account of the number of possible patterns that could exist (e.g., using the [Bonferroni correction]).

If we simplify the failure counts by labelling them as one of Low/Medium/High, then there are two arrangements of the failure counts (i.e., low/medium/high and high/medium/low) that would result in a strong correlation for cpu_speed, two arrangements for memory and two for disc size; a total of 6 combinations that would result in a strong correlation being found.

The [Bonferroni correction] adjusts the significance level by dividing by the number of tests, in this case 0.05/6 = 0.0083.

If the failure counts occurred in a random order what is the probability of a strong correlation between failure count and one of the hardware attributes being found? Based on the Low/Medium/High labelling scheme there are 9!/(3! 3! 3!) = 1680 combinations of these counts over 9 slots, giving a 1 in 1680/6 = 280 chance of purely random behavior producing a strong correlation.

The experiment investigated the characteristics of 11 faults. If there is a 1 in 280 chance of finding a strong correlation when analyzing one fault there is approximately a 1 in 24 chance of finding at least one strong correlation when analysing 11 different faults.

Response variable

The response variable takes the form of a proportion whose value varies between 0 and 1, the number of failures out of 10 executions.

Applicable techniques

The following techniques might be used to analyse this data:

- [Factorial design]. This is a way of organizing experiment configurations that is designed to extract the most information for the total number of program runs made. It would be inefficient not to use the results from some hardware configurations just because they are not needed in the factorial design and no results are available for some configurations required by a factorial design (or a [Plackett-Burman] design).

-

Fitting the data using a linear model. A standard linear model, created using R’s lm function, would not be appropriate because of the following two problems:

- this kind of model is likely to make predictions that fall outside the range 0 to 1, something that cannot happen for proportional data,

- this approach assumes that the variance is constant across measurements and unless the proportions involved are very close to each other this requirement will not be met ([proportional data] from a [binomial distribution] has variance p(1-p)).

However, a generalised linear model would not suffer from these problems. There are several [link functions] that could be used:

- the Poisson distribution, is widely used for modelling faults but requires that the mean and variance have the same value, a property that does not apply to proportional data.

- the Binomial distribution, can handle data having the characteristics present here.

The proportional data is specified in the call to the glm function by having the response variable contain two columns, one containing the number of failures (that is what is being predicted in this case) and the other the number of non-failures. The code looks something like the following (see complete example and data):

y=cbind(fail_count, 10-fail_count) glm(y ~ cpu_speed+memory+disk_size, data=ff_data, family=binomial) |

In this kind of GLM it is assumed that the [residual deviance] is the same as the [residual degrees of freedom]. If the residual deviance is greater than the residual degrees of freedom then [overdispersion] has occurred, which happens for fault 380417. To handle overdispersion the family needs to be changed from binomial to quasibinomial, which in the case of fault 380417 changes the p-value of the fit from 0.0348 to 0.0749.

The analysis of each fault finds that only one of them, 332330, has a significance level within the specified acceptable bounds; this has a negative correlation with CPU speed (i.e., observed failures decrease with clock speed).

With only one faults found to have any significant hardware configuration effects we have to ask about the probability of this experiment finding an effect if one was present.

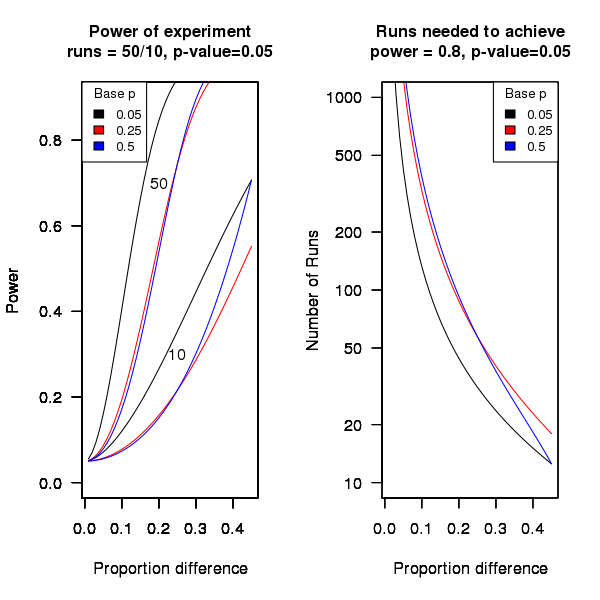

An analysis of the [statistical power] of an experiment investigating the difference between proportions for two hardware configurations (i.e., the percentage of observed failures) needs to know the value of those proportions, the number of runs (10 in this case) and the desired p-value (0.05); to simplify things the plot below is based on using the value of the lowest proportion and the difference between it and the higher proportion. The left plot shows the power achieved (y-axis) there does exist a given difference in proportions (x-axis), the three lowest proportions of 0.05, 0.25 and 0.5 are shown (the result is symmetric about 0.5 and so the plot for 0.75 and 0.95 would be the same as 0.25 and 0.05 respectively), and where there were 10 and 50 runs involving the same fault case.

It can be seen that unless a change in the hardware configuration causes a large change in the number of visible failures then the chance of a difference being detected in results from 10 runs is well below 0.5 (i.e., less than a 50% chance of detecting a difference at a p-value of 0.05 or better).

The right plot in the figure gives the number of runs that need to be made to have a 80% chance of detecting, between two different hardware configurations, the difference in proportion listed on the x-axis, at a significance of 0.05.

It can be seen that if hardware charactersitics account for only 10% of the difference in failure rate over 100 runs would be needed to detect it.

Conclusion

Faults in Firefox that caused intermittent failures were investigated looking for a correlation with system cpu speed, memory or disc size. One fault showed a strong correlation with cpu speed (there is a 1 in 24 chance that one of the investigated faults would have some kind of strong correlation). This experiment may not have found a significant correlation between observed failure rate and hardware configuration because the number of separate runs for each fault (i.e., 10) had [low power].

Trying to sell analysis tools to the Nuclear Regulatory Commission

Over the last few days there has been an interesting, and in places somewhat worrying, discussion going on in the Safety Critical mailing list about the US Nuclear Regulatory Commission. I thought I would tell my somewhat worrying story about dealing with the NRC.

In 1996 the NRC posted a request for information for a tool that I thought my company stood a reasonable chance of being able to meet (“NRC examines source code in nuclear power plant safety systems during the licensing process. NRC is interested in finding commercially available tools that can locate and provide information about the following programming practices…”). I responded, answered the questions on the form I received and was short listed to make a presentation to the NRC.

The presentation took place at the offices of National Institute of Standards and Technology, the government agency helping out with the software expertise.

From our brief email exchanges I had guessed that nobody at the NRC/NIST end knew much about C or static analysis. A typical potential customer occurrence that I was familiar with handling.

Turned up, four or so people from NRC+one(?) from NIST, gave a brief overview and showed how the tool detected the constructs they were interested in, based on test cases I had written after reading their requirements (they had not written any but did give me some code that they happened to have, that was, well, code they happened to have; a typical potential customer occurrence that I was familiar with handling).

Why did the tool produce all those messages? Well, those are the constructs you want flagged. A typical potential customer occurrence that I was familiar with handling.

Does any information have to be given to the tool, such as where to find header files (I knew that they had already seen a presentation from another tool vendor, these managers who appeared to know nothing about software development had obviously picked up this question from that presentation)? Yes, but it is very easy to configure this information… A typical potential customer occurrence that I was familiar with handling.

I asked how they planned to use the tool and what I had to do to show them that this tool met their requirements.

We want one of our inspectors to be able turn up at a reactor site and check their source code. The inspector should not need to know anything about software development and so the tool must be able to run automatically without any options being given and the output must be understandable to the inspector. Not a typical potential customer occurrence and I had no idea about how to handle it (I did notice that my mouth was open and had to make a conscious effort to keep it closed).

No, I would not get to see their final report and in fact I never heard from them again (did they find any tool vendor who did not stare at them in disbelief?)

The trip was not a complete waste of time, a few months earlier I had been at a Java study group meeting (an ISO project that ultimately failed to convince Sun to standarize Java through the ISO process) with some NIST folk who worked in the same building and I got to chat with them again.

A few hours later I realised that perhaps the question I should have asked was “What kind of software are people writing at nuclear facilities that needs an inspector to turn up and check?”

Background to my book project “Empirical Software Engineering with R”

This post provides background information that can be referenced by future posts.

For the last 18 months I have been working in fits and starts on a book that has the working title “Empirical Software Engineering with R”. The idea is to provide broad coverage of software engineering issues from an empirical perspective (i.e., the discussion is driven by the analysis of measurements obtained from experiments); R was chosen for the statistical analysis because it is becoming the de-facto language of choice in a wide range of disciplines and lots of existing books provide example analysis using R, so I am going with the crowd.

While my last book took five years to write I had a fixed target, a template to work to and a reasonably firm grasp of the subject. Empirical software engineering has only really just started, the time interval between new and interesting results appearing is quiet short and nobody really knows what statistical techniques are broadly applicable to software engineering problems (while the normal distribution is the mainstay of the social sciences a quick scan of software engineering data finds few occurrences of this distribution).

The book is being driven by the empirical software engineering rather than the statistics, that is I take a topic in software engineering and analyse the results of an experiment investigating that topic, providing pointers to where readers can find out more about the statistical techniques used (once I know which techniques crop up a lot I will write my own general introduction to them).

I’m assuming that readers have a reasonable degree of numeric literacy, are happy dealing with probabilities and have a rough idea about statistical ideas. I’m hoping to come up with a workable check-list that readers can use to figure out what statistical techniques are applicable to their problem; we will see how well this pans out after I have analysed lots of diverse data sets.

Rather than wait a few more years before I can make a complete draft available for review I have decided to switch to making available individual parts as they are written, i.e., after writing a draft discussion and analysis of each experiment I will published it on this blog (along with the raw data and R code used in the analyse). My reasons for doing this are:

- Reader feedback (I hope I get some) will help me get a better understanding of what people are after from a book covering empirical software engineering from a statistical analysis of data perspective.

- Suggestions for topics to cover. I am being very strict and only covering topics for which I have empirical data and can make that data available to readers. So if you want me to cover a topic please point me to some data. I will publish a list of important topics for which I currently don’t have any data, hopefully somebody will point me at the data that can be used.

- Posting here will help me stay focused on getting this thing done.

Links to book related posts

Distribution of uptimes for high-performance computing systems

Break even ratios for development investment decisions

Agreement between code readability ratings given by students

Changes in optimization performance of gcc over time

Descriptive statistics of some Agile feature characteristics

Impact of hardware characteristics on detectable fault behavior

Prioritizing project stakeholders using social network metrics

Preferential attachment applied to frequency of accessing a variable

Amount of end-user usage of code in Firefox

How many ways of programming the same specification?

Ways of obtaining empirical data in software engineering

What is the error rate for published mathematical proofs?

Changes in the API/non-API method call ratio with program size

Honking the horn for go faster memory (over go faster cpus)

How to avoid being a victim of Brooks’ law

Evidence for the benefits of strong typing, where is it?

Hardware variability may be greater than algorithmic improvement

Extracting the original data from a heatmap image

Entropy: Software researchers go to topic when they have no idea what else to talk about

Maths GCE from 1972 (paper 2)

While sorting through some old papers I came across my GCE maths O level exam papers from the summer of 1972. They are known as GCSE exams these days and are taken by 16 year olds at the end of their final year of compulsory education in the UK. I was lucky enough to have a maths teacher who believed in encouraging students to excel and I (plus five others) took this exam when we were 15. I never got the chance to thank Mr Merritt for the profound effect he had on my life.

For many years the average grades achieved by students in the UK has had a steady upward trend and some people claim the exams are getting easier (others that students are better taught, or at least better taught to pass exams). These days students have calculators and don’t use log tables, so question 3 of Section A is not applicable.

Exam papers in the UK are written by various examining boards. Mine were from the University of London, Syllabus D. I have two papers labeled “Mathematics 2” and “Mathematics 3” and don’t recall if there was ever a “Mathematics 1”. The following are the questions from “Mathematics 2”.

All necessary working must be shown.

- Factorise

Hence, or otherwise, find the exact value of

4 marks

- Given that

, express

, express  in terms of

in terms of  and

and  .

.

3 marks

- Use four digit tables to evaluate

.

.

4 marks

- Given that

is a factor of

is a factor of  , calculate the value of

, calculate the value of  .

.

3 marks

-

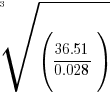

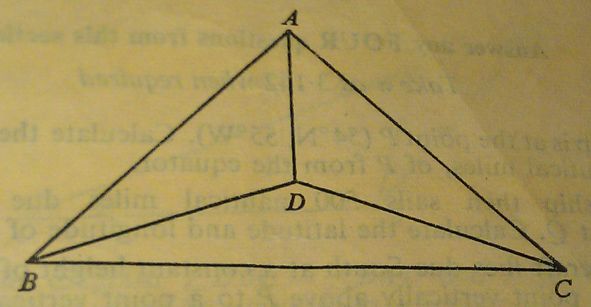

In the diagram ∠DBC = ∠BAD and ADC is a straight line. State which of the two triangles are similar.

If AB = 7 cm, BC = 6 cm and DC = 4 cm, calculate the lengths of AC and BD.

5 marks

- A bicycle wheel has diameter 35 cm. Calculate how many revolutions it makes every minute when the bicycle is travelling at 33 km/h. [ Take

as 22/7 ]

as 22/7 ]

4 marks

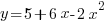

- Calculate the gradient of the curve

at the point (1, -5). Calculate also the coordinates of the point on the curve where the gradient is 1.

at the point (1, -5). Calculate also the coordinates of the point on the curve where the gradient is 1.

4 marks

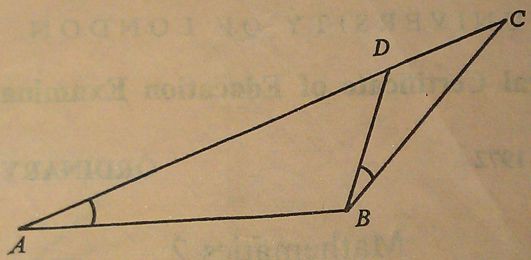

-

In the diagram, AB is parallel to DC, AB = AD and ∠C = 90°. Prove that ∠DAB = 2∠DBC.

5 marks

as 3.142 when required

as 3.142 when required- A ship is at the point P (54°N, 55°W). Calculate the distance, in nautical miles, of P from the equator.

The ship then sails 500 nautical miles due East to a point Q. Calculate the latitude and longitude of Q.

An aircraft flies due South at a constant height of 10 000 m from the point vertically above P to a point vertically above the equator. Taking the earth to be a sphere of radius 6 370 km, calculate the length of the arc along which the aircraft flies.

17 marks

- Draw a circle of radius 5.5 cm. Using ruler and compasses only, construct a tangent to the circle at any point A on its circumference.

Using a protractor, construct the points A, B and C on this circle so that the angles A, B and C of the triangle ABC are 50°, 56° and 74° respectively.

By a further construction using ruler and compasses only, obtain a point X on the tangent at A which is equidistant from the lines AB and BC.

Measure the length of AX.

17 marks

- (i) Find the smallest positive term in the arithmetic progression 76, 74½, 73 … .

Find also the number of positive terns in the progression and the sum of these positive terms.

(ii) The first and fourth terms in a geometric progression are

and

and  respectively. Find the second and third terms of the progression.

respectively. Find the second and third terms of the progression.17 marks

-

The diagram represents a roof-truss in which AB = AC = 8 m, BC = 11 m, BD = DC and ∠DBC = 20°.

Calculate

(a) the length BD,

(b) the angle ABC,

(c) the length AD.

- Draw the graph of

for values of

for values of  from -1 to +4, taking 2 cm as one unit on the x-axis and 1 cm as one unit on the y-axis. From your graph, find the range of values of

from -1 to +4, taking 2 cm as one unit on the x-axis and 1 cm as one unit on the y-axis. From your graph, find the range of values of  for which the function

for which the function  is greater than 6.

is greater than 6.

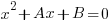

Using the sane axes and scales, draw the graph of

and write down the

and write down the  coordinates of the points of intersection of the two graphs.

coordinates of the points of intersection of the two graphs.if

is the quadratic equation of which these

is the quadratic equation of which these  coordinates are the roots, determine the values of

coordinates are the roots, determine the values of  and

and  .

.17 marks

- A particle starts from rest at a point A and moves along a straight line, coming to rest again at another point B. During the motion its velocity,

metres per second, after time

metres per second, after time  is given by

is given by  .

.

Calculate:

(a) the time taken for the particle to reach B.

(b) the distance travelled during the first two seconds,

(c) the time taken for the particle to attain its maximum velocity,

(d) the maximum velocity attained,

(e) the maximum acceleration during the motion.

17 marks

Automatically generating railroad diagrams from yacc files

Reading and understanding a language’s syntax written in the BNF-like notation used by yacc/bison takes some practice. Railroad diagrams are a much more user friendly notation, but require a lot of manual tweaking before they look as good as the following example from the json.org website:

I’m currently working on a language whose syntax is evolving and I want to create a visual representation of it that can be read by non-yacc experts; spending a day of so manually creating a decent looking railroad diagram is not an efficient use of time. What automatic visualization tools are out there that I can use?

A couple of tools that look like they might produce useful results are web based (e.g., bottlecaps.de; working on an internal project for a company means I cannot take this approach). Some tools take EBNF as input (e.g., my28msec.com which is also online based); the Extensions in EBNF obviate the need for many of the low level organizational details that appear in grammars written with BNF, making grammars written using EBNF easier to layout and look good; great if I was working with EBNF. The yacc file input tools I tried (yaccviso, Vyacc) were a bit too fragile and the output was not that good.

Bison has an option to generate a output that can be processed into graphical form (using graphviz as the layout engine). Unfortunately the graphs produced are as visually tangled as the input grammar and if anything harder to follow.

It is possible to produce great looking visual diagrams using a simple tool if you are willing to spend lots of fiddling with the input grammar to control the output. I wanted to take the grammar as written (i.e., a yacc input file) and am willing to accept less than perfect output.

Most of the syntax rules in a yacc grammar are straight forward sequences of tokens that have an obvious one-to-one mapping and there are a few commonly seen idioms. I decided to write a tool that concentrated on untangling the idioms and let the simple stuff look after itself. One idiom that has a visual representation very different from its yacc form is the two productions used to specify an arbitrary long list, e.g., a semicolon separated list of ys is often written as (ok, there might perhaps be times when right recursion is appropriate):

x : y | x ";" y ; |

and I wanted something that looked like (from the sql-lite web site, which goes one better and allows support for the list to be optional:

Graph layout is a complicated business and like everybody else I decided to use graphviz to do the heavy lifting (specifically I would generate the layout directives used by dot). All I had to do was write a yacc grammar to dot translator (and not spend lots of time doing it).

The dot language provides a directives that specify the visual properties of nodes and the connections between them. For instance:

n_0[shape=point] n_1[label="sql-stmt"] n_2[label=";"] n_3[shape=point] n_0 -> n_3 n_0 -> n_1 n_1 -> n_3 n_1 -> n_2 n_2 -> n_1 |

is the dot specification of the optional semicolon separated list of sql-stmts displayed above.

Dot takes a list of directives describing the nodes and edges of a graph and makes its own decisions about how to layout the output. It is possible to specify in excruciating detail exactly how to do the layout, but I wanted everything to be automated.

I decided to write the tool in awk because it has great input token handling facilities and I use it often enough to be fluent.

Each grammar rule containing one or more productions is mapped to a single graph. When generating postscript dot puts each graph on a separate page, other output formats appear to loose all but one of the graphs. To make sure each rule fitted on a page I had the text point size depend on the number of productions in a rule, more productions smaller point size. The most common idioms are handled (i.e., list-of and optional construct) with hooks available to handle others. Productions within a rule will often have common token sequences but the current version only checks for matching token sequences at the start of a production and all productions in a rule have to start with the same sequence. Words written all in upper-case are assumed to be language tokens and are converted to lower case and bracketed with quotes. The 300+ lines of conversion tool’s awk source is available for download.

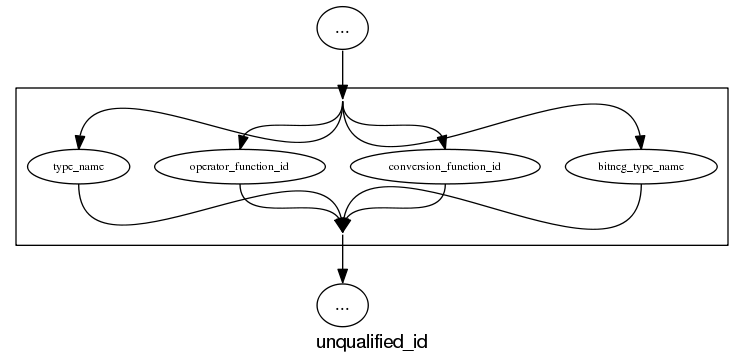

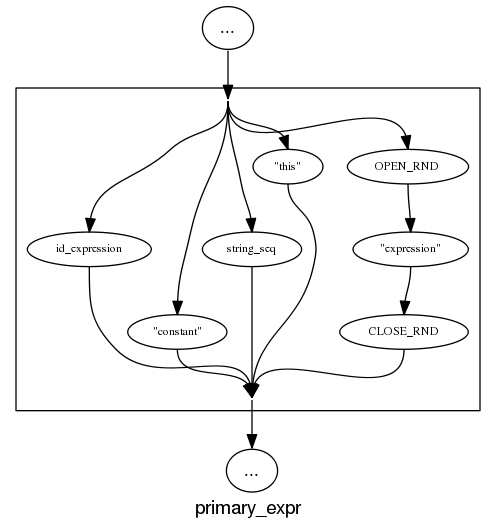

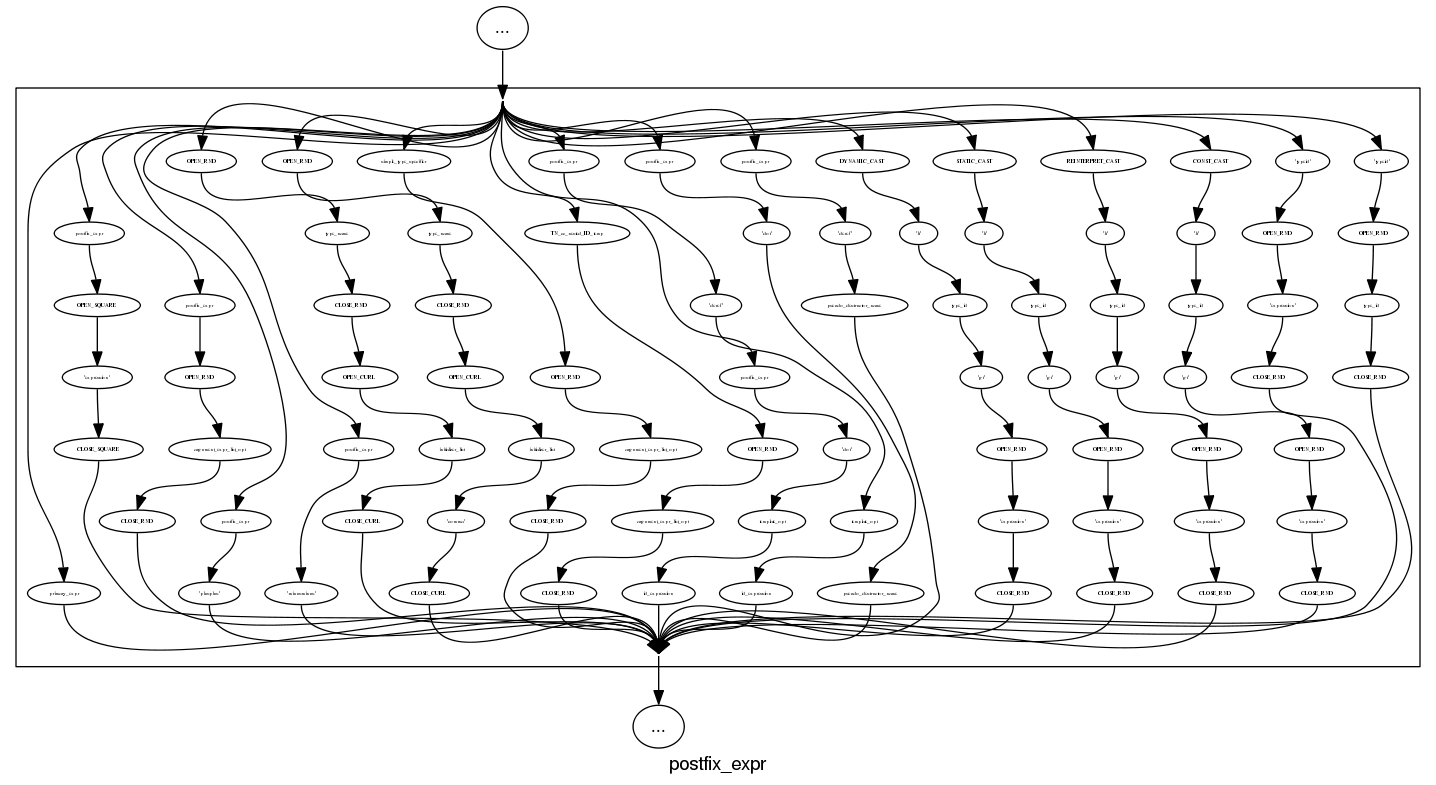

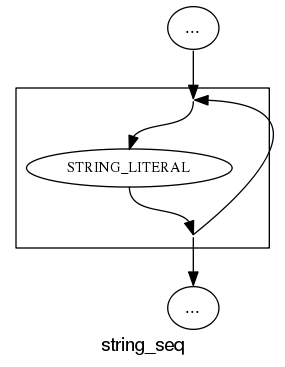

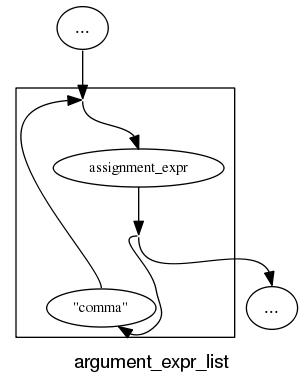

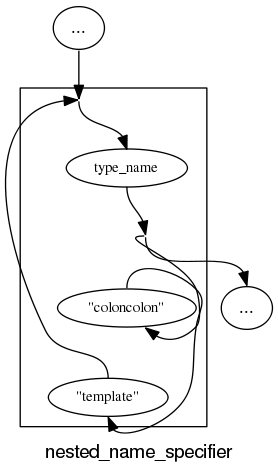

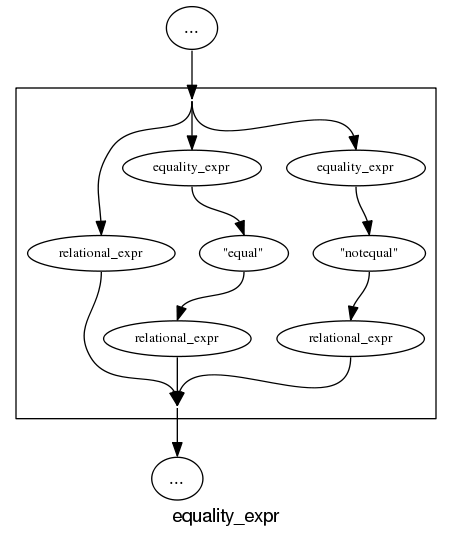

The follow examples are taken from an attempted yacc grammar of C++ done when people still thought such a thing could be created. While the output does have a certain railroad diagram feel to it, the terrain must be very hilly to generate those curvaceous lines.

and the run of the mill rules look good, a C++ primary-expression is:

and we can rely on C++ to push syntax rule complexity to the limit, a postfix-expression is:

What about the idioms? A simple list of items looks good:

and slightly less good when separators are involved:

and if we push our luck things start to look tangled:

With a bit more work invested on merging token sequences common to two or more rules the following might look a lot less cluttered:

Apart from a few tangled cases the results are not bad for a tool that was a few hours work. I will wait a bit to see if the people I deal with find this visual form of use.

In the meantime I would be interested to hear about my readers experience with visualizing grammars, using dot to this kind of thing and any suggestions they have. As a long time user of dot I know that there are lots of ways of influencing the final layout (e.g., changing the ordering or edges and nodes in its input), I will have to be careful not to get pulled down this rabbit hole.

Why do companies fix faults in software they sell?

Once I buy some software from a company they have my money, if sometime later I find a fault software what incentive does that company have to fix the software and provide me with an update (assuming the software is not so fault ridden that I take advantage of laws allowing me to return a purchase for a refund)?

There are three economic incentives for companies to fix faults:

- because I am paying them a fee for updates that include fixes to known faults,

- because they want to make future sales to me and to others (faults encountered by customers contribute towards the perception of product quality),

- they don’t want to lose money because a fault had consequences that resulted in legal action (this reason is overhyped, in practice software engineering has a missing dead body problem).

Which faults get fixed? Software is surprisingly fault-tolerant and there is no point in fixing faults that customers are unlikely to encounter. This means that once a product has been released and known to be acceptable to many customers, there is no incentive to actively search for faults; this means that the only faults likely to be fixed are the ones reported by customers.

When reporting a fault, customers are often asked to rate its severity. This is a useful technique for prioritizing what gets fixed first, or perhaps what does not get fixed at all. Customers who actively set out to find faults are not appreciated and are labelled as disruptive if they continue doing it. Finding faults is surprisingly easy, finding the faults that have a high probability of being encountered by customers and ranked by them as critical is very hard (this is one of the reasons static analysis tools are not widely used).

What is the motivation for developers to fix faults in Open Source?

- There are companies who provide support services for a fee, just like commercial offerings,

- Open Source is free, gaining more users is not an obvious incentive to fix faults. However, being known as the go-to guys for a given package is a way of attracting companies looking to hire somebody to provide support services or make custom modifications to that package. Fixing faults is a way of getting visibility, it is advertising.

- Developers hate the thought of doing something wrong resulting in a fault in code they have written, and writing faulty code is not socially acceptable behavior in software development circles. These feelings about what constitutes appropriate behavior are often enough to make developers want to spend time fixing faults in code they have written or feel responsible for, provided they have the time. I suspect a lot of faults get fixed by developers when their manager/wife thinks they are working on something more ‘useful’.

Would you buy second hand software from a formal methods researcher?

I have been reading a paper on formally proving software correct (Bridging the Gap: Automatic Verified Abstraction of C by Greenaway, Andronick and Klein) and as often the case with papers on this topic the authors have failed to reach the level of honest presentation required by manufacturers of soap power in their adverts.

The Greenaway et al paper describes a process that uses a series of translation steps to convert a C program into what is claimed to be a high level specification in Isabelle/HOL (a language+support tool for doing formal proofs).

The paper was published by an Australian research group; I could not find an Australian advertising standards code dealing with soap power but did find one covering food and beverages. Here is what the Australian Association of National Advertisers has to say in their Food & Beverages Advertising & Marketing Communications Code:

“2.1 Advertising or Marketing Communications for Food or Beverage Products shall be truthful and honest, shall not be or be designed to be misleading or deceptive or otherwise contravene Prevailing Community Standards, and shall be communicated in a manner appropriate to the level of understanding of the target audience of the Advertising or Marketing Communication with an accurate presentation of all information…”

So what claims and statements do Greenaway et al make?

2.1 “Before code can be reasoned about, it must first be translated into the theorem prover.” A succinct introduction to one of the two main tasks, the other being to prove the correctness of these translations.

“In this work, we consider programs in C99 translated into Isabelle/HOL using Norrish’s C parser … As the parser must be trusted, it attempts to be simple, giving the most literal translation of C wherever possible.”

“As the parser must be trusted”? Why must it be trusted? Oh, because there is no proof that it is correct, in fact there is not a lot of supporting evidence that the language handled by Norrish’s translator is an faithful subset of C (ok, for his PhD Norrish wrote a formal semantics of a subset of C; but this is really just a compiler written in mathematics and there are umpteen PhDs who have written compilers for a subset of C; doing it using a mathematical notation does not make it any more fault free).

The rest of the paper describes how the output of Norrish’s translator is generally massaged to make it easier for people to read (e.g., remove redundant statements and rename variables).

Then we get to the conclusion which starts by claiming: “We have presented a tool that automatically abstracts low-level C semantics into higher-level specifications with automatic proofs of correctness for each of the transformation steps.”

Oh no you didn’t. There is no proof for the main transformation step of C to Isabelle/HOL. The only proofs described in the paper are for the post processing fiddling about that was done after the only major transformation step.

And what exactly is this “high-level specification”? The output of the Norrish translator was postprocessed to remove the clutter that invariably gets generated in any high-level language to high-level language translator. Is the result of this postprocessing a specification? Surely it is just a less cluttered representation of the original C?

Actually this paper does contain a major advance in formally proving software correct, tucked away at the start it says “As the parser must be trusted…”. There it is in black and white, if you have some software that must be trusted don’t bother with formal proofs just simply follow the advice given here.

But wait a minute you say, I am ignoring the get out of jail wording “… shall be communicated in a manner appropriate to the level of understanding of the target audience …”. What is the appropriate level of understanding of the target audience, in fact who is the target audience? Is the target audience other formal methods researchers who are familiar with the level of intellectual honesty within their field and take claims made by professional colleagues with a pinch of salt? Are non-formal methods researchers not the target audience and so have no redress to being misled by the any claims made by papers in this field?

Recent Comments