Half-life of Microsoft products is 7 years

I get a lot of pushback from developers/managers when I tell them that the average application has a relatively short lifetime, i.e., half-life of 4-8 years. The pushback kicks in when I start citing data, up until then my listeners appear surprised/skeptical. The fact that source code has a brief and lonely existence is accepted, but telling them about the (one study) evidence that a coding mistake is more likely to disappear because of an unrelated coding change than as a result of fixing a fault report appears to make them feel uncomfortable.

Some applications live a long time, and most developers will spend most of their time working on long-lived applications. Short-lived applications are not around long enough to acquire significant developer/manager mind share.

I think the pushback is rooted in more than developer experience; developers don’t like the thought of their work disappearing from the world. The desire for permanence in what we create may be a human characteristic. Extolling the creation of reliable, maintainable, readable code creates an implicit assumption that applications are going to live long enough for the cost of these activities to be paid back.

How accurate are these half-life estimates?

The 4-8 year half-life range is derived from two datasets. A while ago I spotted another dataset: Fabiano Riccardi‘s Killed by Microsoft, currently containing information on 141 killed products.

All three datasets list just the products that have been killed, i.e., they are not a list of all products. A half-life calculation based only on killed products could underestimate the actual lifetime, it depends on whether the rate of killed products remains roughly the same percentage of all products or not. If the number of products killed, in any period, is always roughly the same percentage of all current products, then the calculated lifetime is not affected by the lack of data on the number of live products. Uncertainty in the calculated lifetime is created when the number of products killed is unconnected with the current number of live products.

It’s possible, to save money, products are more likely to be killed when a company is going through a period of poor performance, or the economy is in recession, compared to when business is booming.

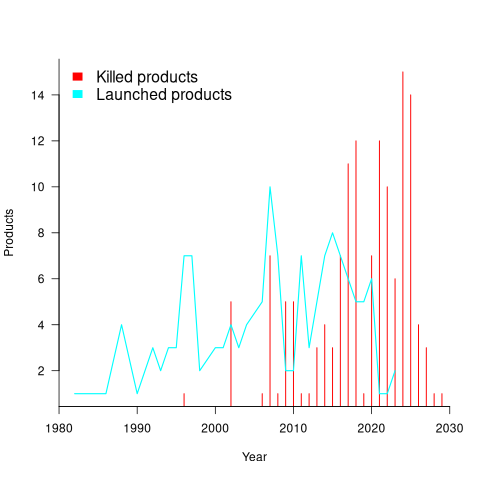

Another source of uncertainty is sampling bias. Companies announce when products are released/withdrawn, creating recency bias because it’s easier to monitor the news than actively search for data on past product releases/withdraws. The plot below shows the number of products Microsoft killed in each year (red bars; post 2025 are to be killed-by dates) and number of new products launched each year blue/green line (code+data):

I’m sure that Microsoft killed more than one product before 2000. The Dot-com bubble burst in March 2000, and I would expect this to have resulted in lots of killed products. The lack of data on products killed before 2000 means that shorter lived products are undercounted.

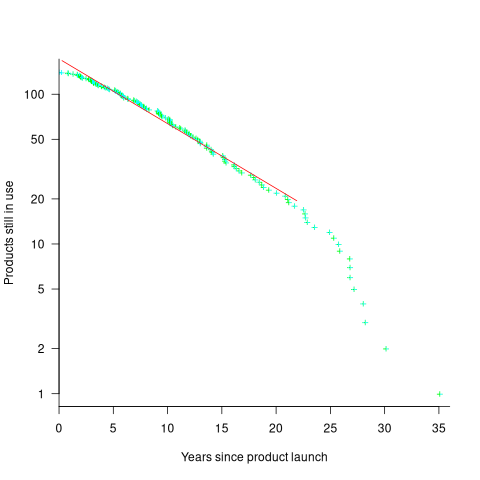

The plot below shows the number of Microsoft (eventually killed) products still supported a given number of years after launch, the red line is a regression fit for products aged between 4 months and 22 years (code+data):

The half-life of the Microsoft products in this dataset, aged between 4 months and 22 years, is 7 years. Is the sharp decline in half-life after 22 years a real thing, or a consequence of the small amount of data before 2005? As always, more data is needed.

Recent Comments