Pricing by quantity of source code

Software tool vendors have traditionally licensed their software on a per-seat basis, e.g., the cost increases with the number of concurrent users. Per-seat licensing works well when there is substantial user interaction, because the usage time is long enough for concurrent usage to build up. When a tool can be run non-interactively in the cloud, its use is effectively instantaneous. For instance, a tool that checks source code for suspicious constructs. Charging by lines of code processed is a pricing model used by some tool vendors.

Charging by lines of code processed creates an incentive to reduce the number of lines. This incentive was once very common, when screens supporting 24 lines of 80 characters were considered a luxury, or the BASIC interpreter limited programs to 1023 lines, or a hobby computer used a TV for its screen (a ‘tiny’ CRT screen, not a big flat one).

It’s easy enough to splice adjacent lines together, and halve the cost. Well, ease of splicing depends on programming language; various edge cases have to be handled (somebody is bound to write a tool that does a good job).

How does the tool vendor respond to a (potential) halving of their revenue?

Blindly splicing pairs of lines creates some easily detectable patterns in the generated source. In fact, some of these patterns are likely to be flagged as suspicious, e.g., if (x) a=1;b=2; (did the developer forget to bracket the two statements with { }).

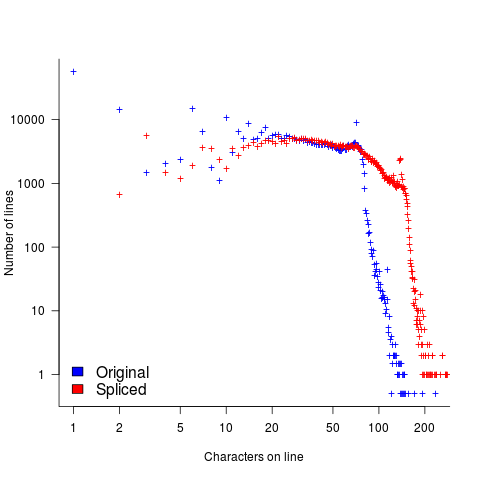

The plot below shows the number of lines in gcc 2.95 containing a given number of characters (left, including indentation), and the same count after even-numbered lines (with leading whitespace removed) have been appended to odd-numbered lines (code+data, this version of gcc was using in my C book):

The obvious change is the introduction of a third straight’ish line segment (the increase in the offset of the sharp decline might be explained away as a consequence of developers using wider windows). By only slicing the ‘right’ pairs of lines together, the obvious patterns won’t be present.

Using lines of codes for pricing has the advantage of being easy to explain to management, the people who sign off the expense, who might not know much about source code. There are other metrics that are much harder for developers to game. Counting tokens is the obvious one, but has developer perception issues: Brackets, both round and curly. In the grand scheme of things, the use/non-use of brackets where they are optional has a minor impact on the token count, but brackets have an oversized presence in developer’s psyche.

Counting identifiers avoids the brackets issue, along with other developer perceptions associated with punctuation tokens, e.g., a null statement in an else arm.

If the amount charged is low enough, social pressure comes into play. Would you want to work for a company that penny pinches to save such a small amount of money?

As a former tool vendor, I’m strongly in favour of tool vendors making a healthy profit.

Creating an effective static analysis requires paying lots of attention to lots of details, which is very time-consuming. There are lots of not particularly good Open source tools out there; the implementers did all the interesting stuff, and then moved on. I know of several groups who got together to build tools for Java when it started to take-off in the mid-90s. When they went to market, they quickly found out that Java developers expected their tools to be free, and would not pay for claimed better versions. By making good enough Java tools freely available, Sun killed the commercial market for sales of Java tools (some companies used their own tools as a unique component of their consulting or service offerings).

Could vendors charge by the number of problems found in the code? This would create an incentive for them to report trivial issues, or be overly pessimistic about flagging issues that could occur (rather than will occur).

Why try selling a tool, why not offer a service selling issues found in code?

Back in the day a living could be made by offering a go-faster service, i.e., turn up at a company and reduce the usage cost of a company’s applications, or reducing the turn-around time (e.g., getting the daily management numbers to appear in less than 24-hours). This was back when mainframes ruled the computing world, and usage costs could be eye-watering.

Some companies offer bug-bounties to the first person reporting a serious vulnerability. These public offers are only viable when the source is publicly available.

There are companies who offer a code review service. Having people review code is very expensive; tools are good at finding certain kinds of problem, and investing in tools makes sense for companies looking to reduce review turn-around time, along with checking for more issues.

Recent Comments