Archive

Functions reduce the need to remember lots of variables

What, if any, are the benefits of adding bureaucracy to a program by organizing a file’s source code into multiple function/method definitions (rather than a single function)?

Having a single copy of a sequence of statements that need to be executed at multiple points in a program reduces implementation effort, and any updates only need to be made once (reducing coding mistakes by removing the need to correctly make duplicate changes). A function/method is the container for this sequence of statements.

Why break code up into separate functions when each is only called once and only likely to ever be called once?

The benefits claimed from splitting code into functions include: making it easier to understand, test, debug, maintain, reuse, and scale development (i.e., multiple developers working on the same program). Our LLM overlords also make these claims, and hallucinate references to published evidence (after three iterations of pointing out the hallucinated references, I gave up asking for evidence; my experience with asking people is that they usually remember once reading something but cannot remember the source).

Regular readers will not be surprised to learn that there is little or no evidence for any of the claimed benefits. I’m not saying that the benefits don’t exist (I think there are some), simply that there have not been any reliable studies attempting to measure the benefits (pointers to such studies welcome).

Having decided to cluster source code into functions, for whatever reason, are there any organizational rules of thumb worth following?

Rules of thumb commonly involve function length (it’s easy to measure) and desirable semantic characteristics of distinct functions (it’s very hard to measure semantic characteristics).

Claims for there being an optimal function length (i.e., lines of code that minimises coding mistakes) turned out to be driven by a mathematical artifact of the axis used when plotting (miniscule) datasets.

Semantic rules of thumb such as: group by purpose, do one thing, and Single-responsibility principle are open to multiple interpretations that often boil down to personal preferences and experience.

One benefit of using functions that is rarely studied is the restricted visibility of local variables defined within them, i.e., only visible within the function body.

When trying to figure out what code does, readers have to keep track of the information contained in all the variables accessed. Having to track more variables not only increases demands on reader memory, it also increases the opportunities for making mistakes.

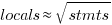

A study of C source found that within a function, the number of local variables is proportional to the square root of the number of statements (code+data). Assuming the proportionality constant is one, a function containing 100 statements might be expected to define 10 local variables. Splitting this function up into, say, four functions containing 25 statements, each is expected to define 5 local variables. The number of local variables that need to be remembered at the same time, when reading a function definition, has halved, although the total number of local variables that need to be remembered when processing those 100 statements has doubled. Some number of global variables and function parameters need to be added to create an overall total for the number of variables.

The plot below shows the number of locals defined in 36,617 C functions containing a given number of statements, the red line is a fitted regression model having the form:  (code+data):

(code+data):

My experience with working with recently self-taught developers, especially very intelligent ones, is that they tend to write monolithic programs, i.e., everything in one function in one file. This minimal bureaucracy approach minimises the friction of a stream of thought development process for adding new code, and changing existing code as the program evolves. Most of these programs are small (i.e., at most a few hundred lines). Assuming that these people continue to code, one of two events teaches them the benefits of function bureaucracy:

- changes to older programs becomes error-prone. This happens because the developer has forgotten details they once knew, e.g., they forget which variables are in use at particular points in the code,

- the size of a program eventually exceeds their ability to remember all of it (very intelligent people can usually remember much larger programs than the rest of us). Coding mistakes occur because they forget which variables are in use at particular points in the code.

Correlation between risk attitude and willingness to refer back

What is the connection between a software developer’s risk attitude and the faults they insert in code they write or fail to detect in code they review? This is a very complicated question and in an experiment performed at the 2011 ACCU conference I investigated one particular instance; the connection between risk attitude and recall of previously seen information.

The experiment consisted of a series of problems having the same format (the identifiers used varied between problems). Each problem involved remembering information on four assignment statements of the form:

p = 6 ; b = 4 ; r = 9 ; k = 8 ; |

performing some other unrelated task for a short time (hopefully long enough for them to forget some of the information they had previously seen) and then having to recognize the variables they had previously seen within a list containing five identifiers and recall the numeric value assigned to each variable.

When reading code developers have the option of referring back to previously read code and this option was provided to subject. Next to each identifier listed in the recall part of the problem was space to write the numeric value previously seen and a “would refer back” box. Subjects were told to tick the “would refer back” box if, in real life” they would refer back to the previously seen assignment statements rather than rely on their memory.

As originally conceived this experimental format is investigating the impact of human short term memory on recall of previously seen code. Every time I ran this kind of experiment there was a small number of subjects who gave a much higher percentage of “would refer back” answers than the other subjects. One explanation was that these subjects had a smaller short term memory capacity than other subjects (STM capacity does vary between people), another explanation is that these subjects are much more risk averse than the other subjects.

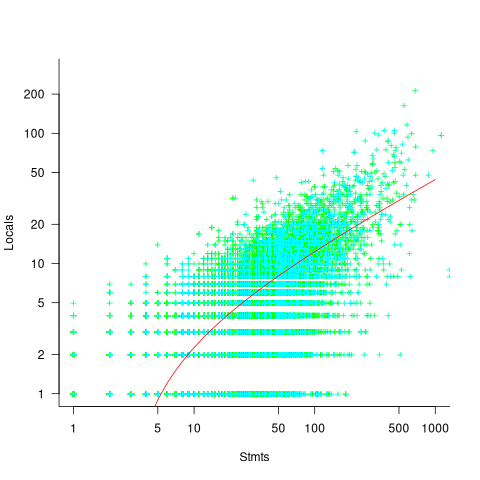

The 2011 ACCU experiment was designed to test the hypothesis that there was a correlation between a subject’s risk attitude and the percentage of “would refer back” answers they gave. The Domain-Specific Risk-Taking (DOSPERT) questionnaire was used to measure subject’s risk attitude. This questionnaire and the experimental findings behind it have been published and are freely available for others to use. DOSPERT measures risk attitude in six domains: social, recreation, gambling, investing health and ethical.

The following scatter plot shows each (of 30) subject’s risk attitude in the six domains (x-axis) plotted against percentage of “would refer back” answers (y-axis).

A Spearman rank correlation test confirms what is visibly apparent, there is no correlation between the two quantities. Scatter plots using percentage of correct answers and total number of questions answers show a similar lack of correlation.

The results suggest that risk attitude (at least as measured by DOSPERT) is not a measurable factor in subject recall performance. Perhaps the subjects that originally caught my attention (there were three in 2011) really do have a smaller STM capacity compared to other subjects. The organization of the experiment (one hour during a one lunchtime of the conference) does not allow for a more extensive testing of subject cognitive characteristics.

Unexpected experimental effects

The only way to find out the factors that effect developers’ source code performance is to carry out experiments where they are the subjects. Developer performance on even simple programming tasks can be effected by a large number of different factors. People are always surprised at the very small number of basic operations I ask developers to perform in the experiments I run. My reply is that only by minimizing the number of factors that might effect performance can I have any degree of certainty that the results for the factors I am interested in are reliable.

Even with what appear to be trivial tasks I am constantly surprised by the factors that need to be controlled. A good example is one of the first experiments I ever ran. I thought it would be a good idea to replicate, using a software development context, a widely studied and reliably replicated human psychological effect; when asked to learn and later recall/recognize a list of words people make mistakes. Psychologists study this problem because it provides a window into the operation structure of the human memory subsystem over short periods of time (of the order of at most tens of seconds). I wanted to find out what sort of mistakes developers would make when asked to remember information about a sequence of simple assignment statements (e.g.,

qbt = 6;).I carefully read the appropriate experimental papers and had created lists of variables that controlled for every significant factor (e.g., number of syllables, frequency of occurrence of the words in current English usage {performance is better for very common words}) and the list of assignment statements was sufficiently long that it would just overload the capacity of short term memory (about 2 seconds worth of sound).

The results contained none of the expected performance effects, so I ran the experiment again looking for different effects; nothing. A chance comment by one of the subjects after taking part in the experiment offered one reason why the expected performance effects had not been seen. By their nature developers are problem solvers and I had set them a problem that asked them to remember information involving a list of assignment statements that appeared to be beyond their short term memory capacity. Problem solvers naturally look for patterns and common cases and the variables in each of my carefully created list of assignment statements could all be distinguished by their first letter. Subjects did not need to remember the complete variable name, they just needed to remember the first letter (something I had not controlled for). Asking around I found that several other subjects had spotted and used the same strategy. My simple experiment was not simple enough!

I was recently reading about an experiment that investigated the factors that motivate developers to comment code. Subjects were given some code and asked to add additional functionality to it. Some subjects were given code containing lots of comments while others were given code containing few comments. The hypothesis was that developers were more likely to create comments in code that already contained lots of comments, and the results seemed to bear this out. However, closer examination of the answers showed that most subjects had cut and pasted chunks (i.e., code and comments) from the code they were given. So code the percentage of code in the problem answered mimicked that in the original code (in some cases subjects had complicated the situation by refactoring the code).