Archive

Adding house numbers to Open Street Map

Team OSM-house-numbers (Pavel and yours truly) was at the Open Street Map London hack weekend a few days ago.

When Phyllis Pearsall was out walking the streets of London in the 1930s gathering information for her Geographer’s A-Z London street map she recorded house numbers and included this information on her maps. House number information is included in OSM data when people have added it. Is there a way of automatically adding this information in bulk?

The UK Land Registry maintains a database of house sales; the information includes postcode, street and house number. The database is available under the Open Government License, which is compatible with the OSM license.

It is straight-forward to match all house sales having the same postcode/street to obtain a min/max house number for a postcode/street.

The first half of a UK postcode specifies a large area or district (e.g., GU14 is my district code), while the second half has a granularity of around a quarter of a mile or less (depending on housing density).

It was decided that house numbers on a map become useful when streets are long enough, where long enough is defined as containing houses having different postcodes. Assuming that street names are unique within a given postcode district, filtering out not-long enough streets was trivial.

The Land registry started recording sales in 1995 and it is possible that some streets are not considered to be long enough because they contain houses that have not been sold within the last 20 years; this problem will also affect the min/max value of some house number ranges.

To tie this postcode/street information to Open Street Map data we need latitude/longitude information.

Information on house number locations is very useful to governments and in the UK is collected by our national mapping body, the Ordinance Survey, who like all UK government bodies have a long history of being loath to make information available for general public use. The current situation, according to Wikipedia, is that the Ordinance Survey mapping from postcode to latitude/longitude is available as open data.

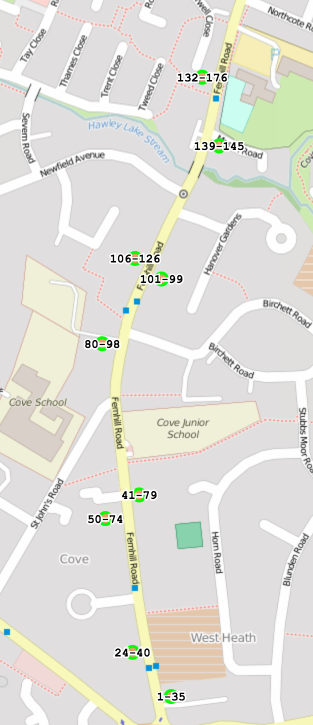

Adding information for postcode lat/long and feeding everything into a webpage produces a map such as the one below (opposite sides of the street having different postcodes is plainly visible):

We cannot guarantee that the house number data we have created is 100% accurate; there may be mistakes in our code or the Land registry/Ordinance Survey data we processed. Experienced OSM hackers at the event told us about minor mistakes in automatically generated data, that had occurred in the past and had a disproportionate impact on user confidence in OSM accuracy. So we did not upload our data to OSM; you can find it on github (saved in compressed form to reduce download time), along with the code used to create it.

The hackathon finished at five, with people decamping to a local pub. We were more or less done by three. What next (perhaps for another hackathon or a dedicated OSM hacker)?

What is needed is a simple way to overlay house number range information on an OSM image which can be easily used by people with local knowledge to confirm whether it is correct or not, with the data being added to OSM if it is correct.

Other possible OSM uses for the Land registry data include estimating density of houses along a street, e.g., number-of-unique-house-numbers divided by distance-between-adjacent-postcodes and perhaps even a house price heatmap (ok, that’s a bit specialized).

What about trees? This is my tree hugging side showing itself. If you plan to go out mapping house numbers, don’t forget to map the trees!

Apps in Space Hackathon

I went along to the Satellite Applications hackathon last weekend. As a teenager I was very much into space flight and with this event being only 30 miles away how could I not attend. Around 25 or so hackers turned up, supported by seven or so knowledgeable and motivated people from the organizers/sponsors. Excellent food+drink, including sending out for Indian/Chinese for dinner. The one important item in short supply was example data to experiment with; the organizers are aware of this and plan to have a lot more data available at the next event.

The rationale for the event is to encourage the creation of business activities in the UK around the increasing amount of data beamed to Earth from satellites. At the moment a satellite image costs something like £100 if its in the back catalog and £10,000 if you want them to take one just for you; the price of images in the back catalog is about to plummet (new satellites coming on stream) and a company is being set up to act as a one stop shop+good user interface for pics (at the moment customers have to talk to a variety of suppliers to find see what’s available). I was excited to hear that I could have my own satellite launched for £100,000, the catch being that they are a bit more expensive to build.

Making use of satellite data requires other data plus support software. Many of the projects people decided to work on needed access to mapping data, e.g., which road is closest to this latitude/longitude. Open Streetmap is the obvious source of mapping data, the UK’s Ordinance Survey have also made some data freely available for public/commercial use. The current problem with this data is the lack of support libraries designed to handle satellite related queries (e.g., return nearest road, town, etc), the existing APIs are good for creating mapping images and dealing with routing.

Support for very large images is one area where existing tools are going to need an upgrade; by very large I mean single image files measured in gigabytes. I did not manage to view any gigabyte image files on my laptop (with 4G of ram), even after going for a coffee and sitting talking to somebody waiting for it to cool before drinking it, still a black rectangle. If the price of satellite images plummets and are easy to buy online, then I can imagine them becoming a discretionary item that people buy for a bit of fun and will then want to view using the devices they already own; telling them that this is not sensible is the wrong answer, the customer is always right and it has to be made to work.

One area where there is good software tool support is working out where satellites will appear in the sky; this is really an astronomical application and there are lots of astronomical tools out there. The Python crowd will be happy to know that scientific-grade astronomy routines are available in Pyephem.

For the most part the hacks created are bullet points of ideas and things to do. The team working on calculating the satellite beam likely to have the strongest signal at a given point on the Earth’s surface made a lot more progress than anybody else. This is because they had an existing Python library to use and ‘only’ needed to apply the trigonometry that we all learn in school.

Some suggestions for the organizers:

- put lightening talks on existing technologies and some of their uses on the agenda (the brief presentation given on SAR was eye opening),

- make some good example data public, i.e., downloadable for all to use. This is the only way to get lots of library support written,

- create cut-down datasets that are usable on laptops. At a Hackathon people can only productively use what they know well and requiring them to use something unfamiliar, such as a virtual machine, is a major road block,

- allow external users to take part, why limit your potential customer base to what can be fitted into a medium size room?

Recent Comments