Archive

2023 in the programming language standards’ world

Two weeks ago I was on a virtual meeting of IST/5, the committee responsible for programming language standards in the UK. IST/5 has a new chairman, Guy Davidson, whose efficiency is very unstandard’s like.

It’s been 18 months since I last reported on the programming language standards’ world, what has been going on?

2023 is going to be a bumper year for the publication of revised Standards of long-established programming language: COBOL, Fortran, C, and C++ (a revised Standard for Ada was published last year).

Yes, COBOL; a new COBOL Standard was published in January. Reports of its death were premature, e.g., my 2014 post suggesting that the latest version would be the last version of the Standard, and the closing of PL22.4, the US Cobol group, in 2017. There has even been progress on the COBOL front end for gcc, which now supports COBOL 85.

The size of the COBOL Standard has leapt from 955 to 1,229 pages (around new 200 pages in the normative text, 100 in the annexes). Comparing the 2014/2023 documents, I could not see any major additions, just lots of small changes spread throughout the document.

Every Standard has a project editor, the person tasked with creating a document that reflects the wishes/votes of its committee; the project editor sends the agreed upon document to ISO to be published as the official ISO Standard. The ISO editors would invariably request that the project editor make tiresome organizational changes to the document, and then add a front page and ISO copyright notice; from time to time an ISO editor took it upon themselves to reformat a document, sometimes completely mangling its contents. The latest diktat from ISO requires that submitted documents use the Cambria font. Why Cambria? What else other than it is the font used by the Microsoft Word template promoted by ISO as the standard format for Standard’s documents.

All project editors have stories to tell about shepherding their document through the ISO editing process. With three Standards (COBOL lives in a disjoint ecosystem) up for publication this year, ISO editorial issues have become a widespread topic of discussion in the bubble that is language standards.

Traditionally, anybody wanting to be actively involved with a language standard in the UK had to find the contact details of the convenor of the corresponding language panel, and then ask to be added to the panel mailing list. My, and others, understanding was that provided the person was a UK citizen or worked for a UK domiciled company, their application could not be turned down (not that people were/are banging on the door to join). BSI have slowly been computerizing everything, and, as of a few years ago, people can apply to join a panel via a web page; panel members are emailed the CV of applicants and asked if “… applicant’s knowledge would be beneficial to the work programme and panel…”. In the US, people pay an annual fee for membership of a language committee ($1,340/$2,275). Nobody seems to have asked whether the criteria for being accepted as a panel member has changed. Given that BSI had recently rejected somebodies application to join the C++ panel, the C++ panel convenor accepted the action to find out if the rules have changed.

In December, BSI emailed language panel members asking them to confirm that they were actively participating. One outcome of this review of active panel membership was the disbanding of panels with ‘few’ active members (‘few’ might be one or two, IST/5 members were not sure). The panels that I know to have survived this cull are: Fortran, C, Ada, and C++. I did not receive any email relating to two panels that I thought I was a member of; one or more panel convenors may be appealing their panel being culled.

Some language panels have been moribund for years, being little more than bullet points on the IST/5 agenda (those involved having retired or otherwise moved on).

2021 in the programming language standards’ world

Last Tuesday I was on a Webex call (the British Standards Institute’s use of Webex for conference calls predates COVID 19) for a meeting of IST/5, the committee responsible for programming language standards in the UK.

There have been two developments whose effect, I think, will be to hasten the decline of the relevance of ISO standards in the programming language world (to the point that they are ignored by compiler vendors).

- People have been talking about switching to online meetings for years, and every now and again someone has dialed-in to the conference call phone system provided by conference organizers. COVID has made online meetings the norm (language working groups have replaced face-to-face meetings with online meetings). People are looking forward to having face-to-face meetings again, but there is talk of online attendance playing a much larger role in the future.

The cost of attending a meeting in person is the perennial reason given for people not playing an active role in language standards (and I imagine other standards). Online attendance significantly reduces the cost, and an increase in the number of people ‘attending’ meetings is to be expected if committees agree to significant online attendance.

While many people think that making it possible for more people to be involved, by reducing the cost, is a good idea, I think it is a bad idea. The rationale for the creation of standards is economic; customer costs are reduced by reducing

diversityincompatibilities across the same kind of product., e.g., all standard conforming compilers are consistent in their handling of the same construct (undefined behavior may be consistently different). When attending meetings is costly, those with a significant economic interest tend to form the bulk of those attending meetings. Every now and again somebody turns up for a drive-by-shooting, i.e., they turn up for a day to present a paper on their pet issue and are never seen again.Lowering the barrier to entry (i.e., cost) is going to increase the number of drive-by shootings. The cost of this spray of pet-issue papers falls on the regular attendees, who will have to spend time dealing with enthusiastic, single issue, newbies,

- The International Organization for Standardization (ISO is the abbreviation of the French title) has embraced the use of inclusive terminology. The ISO directives specifying the Principles and rules for the structure and drafting of ISO and IEC documents, have been updated by the addition of a new clause: 8.6 Inclusive terminology, which says:

“Whenever possible, inclusive terminology shall be used to describe technical capabilities and relationships. Insensitive, archaic and non-inclusive terms shall be avoided. For the purposes of this principle, “inclusive terminology” means terminology perceived or likely to be perceived as welcoming by everyone, regardless of their sex, gender, race, colour, religion, etc.

New documents shall be developed using inclusive terminology. As feasible, existing and legacy documents shall be updated to identify and replace non-inclusive terms with alternatives that are more descriptive and tailored to the technical capability or relationship.”

The US Standards body, has released the document INCITS inclusive terminology guidelines. Section 5 covers identifying negative terms, and Section 6 deals with “Migration from terms with negative connotations”. Annex A provides examples of terms with negative connotations, preceded by text in bright red “CONTENT WARNING: The following list contains material that may be harmful or

traumatizing to some audiences.”“Error” sounds like a very negative word to me, but it’s not in the annex. One of the words listed in the annex is “dummy”. One member pointed out that ‘dummy’ appears 794 times in the current Fortran standard, (586 times in ‘dummy argument’).

Replacing words with negative connotations leads to frustration and distorted perceptions of what is being communicated.

I think there will be zero real world impact from the use of inclusive terminology in ISO standards, for the simple reason that terminology in ISO standards usually has zero real world impact (based on my experience of the use of terminology in ISO language standards). But the use of inclusive terminology does provide a new opportunity for virtue signalling by members of standards’ committees.

While use of inclusive terminology in ISO standards is unlikely to have any real world impact, the need to deal with suggested changes of terminology, and new terminology, will consume committee time. Most committee members tend to a rather pragmatic, but it only takes one or two people to keep a discussion going and going.

Over time, compiler vendors are going to become disenchanted with the increased workload, and the endless discussions relating to pet-issues and inclusive terminology. Given that there are so few industrial strength compilers for any language, the world no longer needs formally agreed language standards; the behavior that implementations have to support is controlled by the huge volume of existing code. Eventually, compiler vendors will sever the cord to the ISO standards process, and outside the SC22 bubble nobody will notice.

2019 in the programming language standards’ world

Last Tuesday I was at the British Standards Institute for a meeting of IST/5, the committee responsible for programming language standards in the UK.

There has been progress on a few issues discussed last year, and one interesting point came up.

It is starting to look as if there might be another iteration of the Cobol Standard. A handful of people, in various countries, have started to nibble around the edges of various new (in the Cobol sense) features. No, the INCITS Cobol committee (the people who used to do all the heavy lifting) has not been reformed; the work now appears to be driven by people who cannot let go of their involvement in Cobol standards.

ISO/IEC 23360-1:2006, the ISO version of the Linux Base Standard, has been updated and we were asked for a UK position on the document being published. Abstain seemed to be the only sensible option.

Our WG20 representative reported that the ongoing debate over pile of poo emoji has crossed the chasm (he did not exactly phrase it like that). Vendors want to have the freedom to specify code-points for use with their own emoji, e.g., pineapple emoji. The heady days, of a few short years ago, when an encoding for all the world’s character symbols seemed possible, have become a distant memory (the number of unhandled logographs on ancient pots and clay tablets was declining rapidly). Who could have predicted that the dream of a complete encoding of the symbols used by all the world’s languages would be dashed by pile of poo emoji?

The interesting news is from WG9. The document intended to become the Ada20 standard was due to enter the voting process in June, i.e., the committee considered it done. At the end of April the main Ada compiler vendor asked for the schedule to be slipped by a year or two, to enable them to get some implementation experience with the new features; oops. I have been predicting that in the future language ‘standards’ will be decided by the main compiler vendors, and the future is finally starting to arrive. What is the incentive for the GNAT compiler people to pay any attention to proposals written by a bunch of non-customers (ok, some of them might work for customers)? One answer is that Ada users tend to be large bureaucratic organizations (e.g., the DOD), who like to follow standards, and might fund GNAT to implement the new document (perhaps this delay by GNAT is all about funding, or lack thereof).

Right on cue, C++ users have started to notice that C++20’s added support for a system header with the name version, which conflicts with much existing practice of using a file called version to contain versioning information; a problem if the header search path used the compiler includes a project’s top-level directory (which is where the versioning file version often sits). So the WG21 committee decides on what it thinks is a good idea, implementors implement it, and users complain; implementors now have a good reason to not follow a requirement in the standard, to keep users happy. Will WG21 be apologetic, or get all high and mighty; we will have to wait and see.

Cobol 2014, perhaps the definitive final version of the language…

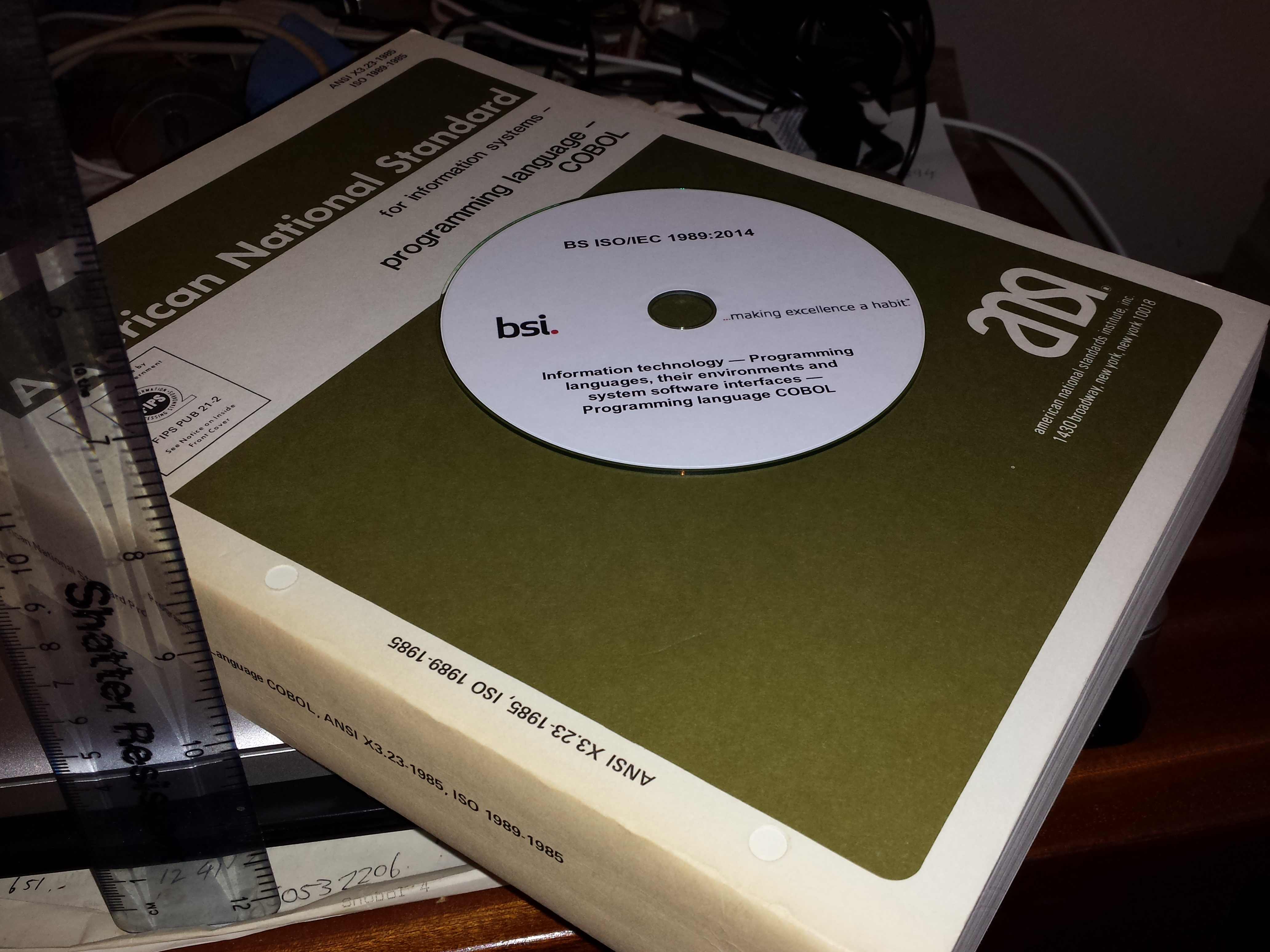

Look what arrived in the post this morning, a complementary copy of the new Cobol Standard (the CD on top of a paper copy of the 1985 standard).

In the good old days, before the Internet, members of IST/5 received a complementary copy of every new language standard in comforting dead tree form (a standard does not feel like a standard until it is weighed in the hand; pdfs are so lightweight); these days we get complementary access to pdfs. I suspect that this is not a change of policy at British Standards, but more likely an excessive print run that they need to dispose of to free up some shelf space. But it was nice of them to think of us workers rather than binning the CDs (my only contribution to Cobol 2014 was to agree with whatever the convener of the committee proposed with regard to Cobol).

So what does the new 955-page standard have to say for itself?

“COBOL began as a business programming language, but its present use has spread well beyond that to a general purpose programming language. Significant enhancements in this International Standard include:

— Dynamic-capacity tables

— Dynamic-length elementary items

— Enhanced locale support in functions

— Function pointers

— Increased size limit on alphanumeric, boolean, and national literals

— Parametric polymorphism (also known as method overloading)

— Structured constants

— Support for industry-standard arithmetic rules

— Support for industry-standard date and time formats

— Support for industry-standard floating-point formats

— Support for multiple rounding options”

I guess those working with Cobol will find these useful, but I don’t see them being enough to attract new users from other languages.

I have heard tentative suggestions of the next revision appearing in the 2020s, but with membership of the Cobol committee dying out (literally in some cases and through retirement in others) perhaps this 2014 publication is the definitive final version of Cobol.

An ISO Standard for R (just kidding)

IST/5, the British Standards’ committee responsible for programming languages in the UK, has a new(ish) committee secretary and like all people in a new role wants to see a vision of the future; IST/5 members have been emailed asking us what we see happening in the programming language standards’ world over the next 12 months.

The answer is, off course, that the next 12 months in programming language standards is very likely to be the same as the previous 12 months and the previous 12 before that. Programming language standards move slowly, you don’t want existing code broken by new features and it would be a huge waste of resources creating a standard for every popular today/forgotten tomorrow language.

While true the above is probably not a good answer to give within an organization that knows its business intrinsically works this way, but pines for others to see it as doing dynamic, relevant, even trendy things. What could I say that sounded plausible and new? Big data was the obvious bandwagon waiting to be jumped on and there is no standard for R, so I suggested that work on this exciting new language might start in the next 12 months.

I am not proposing that anybody start work on an ISO standard for R, in fact at the moment I think it would be a bad idea; the purpose of suggesting the possibility is to create some believable buzz to suggest to those sitting on the committees above IST/5 that we have our finger on the pulse of world events.

The purpose of a standard is to create agreement around one way of doing things and thus save lots of time/money that would otherwise be wasted on training/tools to handle multiple language dialects. One language for which this worked very well is C, for which there were 100+ incompatible compilers in the early 1980s (it was a nightmare); with the publication of the C Standard users finally had a benchmark that they could require their suppliers to meet (it took 4-5 years for the major suppliers to get there).

R is not suffering from a proliferation of implementations (incompatible or otherwise), there is no problem for an R standard to solve.

Programming language standards do get created for reasons other than being generally useful. The ongoing work on C++ is a good example of consultant driven standards development; consultants who make their living writing and giving seminars about the latest new feature of C++ require a steady stream of new feature to talk about and have an obvious need to keep new versions of the standard rolling down the production line. Feeling that a language is unappreciated is another reason for creating an ISO Standard; the Modula-2 folk told me that once it became an ISO Standard the use of Modula-2 would take off. R folk seem to have a reasonable grip on reality, or have I missed a lurking distorted view of reality that will eventually give people the drive to spend years working their fingers to the bone to create a standard that nobody is really that interested in?

2013 in the programming language standards’ world

Yesterday I was at the British Standards Institute for a meeting of IST/5, the committee responsible for programming languages. Things have been rather quiet since I last wrote about IST/5, 18 months ago. Of course lots of work has been going on (WG21 meetings, C++ Standard, are attracting 100+ people, twice a year, to spend a week trying to reach agreement on new neat features to add; I’m not sure how the ability to send email is faring these days ;-).

Taken as a whole programming languages standards work, at the ISO level, has been in decline over the last 10 years and will probably decline further. IST/5 used to meet for a day four times a year and now meets for half a day twice a year. Chairman of particular language committees, at international and national levels, are retiring and replacements are thin on the ground.

Why is work on programming language standards in decline when there are languages in widespread use that have not been standardised (e.g., Perl and PHP do not have a non-source code specification)?

The answer is low hardware/OS diversity and Open source. These two factors have significantly reduced the size of the programming language market (i.e., there are far fewer people making a living selling compilers and language related tools). In the good old-days any computer company worth its salt had its own cpu and OS, which of course needed its own compiler and the bigger vendors had third parties offering competing compilers; writing a compiler was such a big undertaking that designers of new languages rarely gave the source away under non-commercial terms, even when this happened the effort involved in a port was heroic. These days we have a couple of cpus in widespread use (and unlikely to be replaced anytime soon), a couple of OSs and people are queuing up to hand over the source of the compiler for their latest language. How can a compiler writer earn enough to buy a crust of bread let alone attend an ISO meeting?

Creating an ISO language standard, through the ISO process, requires a huge amount of work (an estimated 62-person years for C99; pdf page 20). In a small market, few companies have an incentive to pay for an employee to be involved in the development process. Those few languages that continue to be worked on at the ISO level have niche markets (Fortran has supercomputing and C had embedded systems) or broad support (C and now C++) or lots of consultants wanting to be involved (C++, not so much C these days).

The new ISO language standards are coming from national groups (e.g., Ruby from Japan and ECMAscript from the US) who band together to get the work done for local reasons. Unless there is a falling out between groups in different nations, and lots of money is involved, I don’t see any new language standards being developed within ISO.

Does the UK need the PL/1 Standard?

Like everything else language standards are born and eventually die. IST/5, the UK programming language committee, is considering whether the British Standard for PL/1 should be withdrawn (there are two standards, ISO 6160:1979 which has been reconfirmed multiple times since 1979, most recently in 2008, and a standardized subset ISO 6522:1992, also last confirmed in 2008).

A language standard is born through the efforts of a group of enthusiastic people. A language standard dies because there is no enthusiast (a group of one is often sufficient) to sing its praises (or at least be willing to be a name on a list that is willing to say, every five years, that the existing document should be reconfirmed).

It is 20 years since IST/5 last had a member responsible for PL/1, but who is to say that nobody in the UK is interested in maintaining the PL/1 standard? Unlike many other programming language ISO Standards there was never an ISO SC22 committee responsible for PL/1. All of the work was done by members of the US committee responsible for programming language PL 22 (up until a few years ago this was ANSI committee X3). A UK person could have paid his dues and been involved in the US based work; I don’t have access to a list of committee meeting attendees and so cannot say for sure that there was no UK involvement.

A member of IST/5, David Muxworthy, has been trying to find somebody in the UK with an interest in maintaining the PL/1 standard. A post to the newsgroup comp.lang.pl1 eventually drew a response from a PL/1 developer who said he would not be affected if the British Standard was withdrawn.

GNU compiler development is often a useful source of information. In this case the PL/1 web page is dated 2007.

In 2008 John Klensin, the ISO PL/1 project editor, wrote: “No activities or requests for additions or clarifications during the last year or, indeed, the last decade. Both ISO 6160 and the underlying US national document, ANS X3.53-1976 (now ANSI/INCITS-53/1976), have been reaffirmed multiple times. The US Standard has been stabilized and the corresponding technical activity was eliminated earlier this year”.

It looks like the British Standard for PL/1 is not going to live past the date of its next formal review in 2013. Thirty four years would then be the time span, from publication of last standard containing new material to formal withdrawal of all standards, to outlive. I wonder if any current member of either of the C or C++ committees will live to see this happen to their work?

Ruby becoming an ISO Standard

The Ruby language is going through the process of becoming an ISO Standard (it has been assigned the document number ISO/IEC 30170).

There are two ways of creating an ISO Standard, a document that has been accepted by another standards’ body can be fast tracked to be accepted as-is by ISO or a committee can be set up to write the document. In the case of Ruby a standard was created under the auspices of JISC (Japanese Industrial Standards Committee) and this has now been submitted to ISO for fast tracking.

The fast track process involves balloting the 18 P-members of SC22 (the ISO committee responsible for programming languages), asking for a YES/NO/ABSTAIN vote on the submitted document becoming an ISO Standard. NO votes have to be accompanied by a list of things that need to be addressed for the vote to change to YES.

In most cases the fast tracking of a document goes through unnoticed (Microsoft’s Office Open XML being a recent high profile exception). The more conscientious P-members attempt to locate national experts who can provide worthwhile advice on the country’s response, while the others usually vote YES out of politeness.

Once an ISO Standard is published future revisions are supposed to be created using the ISO process (i.e., a committee attended by interested parties from P-member countries proposes changes, discusses and when necessary votes on them). When the C# ECMA Standard was fast tracked through ISO in 2005 Microsoft did not start working with an ISO committee but fast tracked a revised C# ECMA Standard through ISO; the UK spotted this behavior and flagged it. We will have to wait and see where work on any future revisions takes place.

Why would any group want to make the effort to create an ISO Standard? The Ruby language designers reasons appear to be “improve the compatibility between different Ruby implementations” (experience shows that compatibility is driven by customer demand not ISO Standards) and government procurement in Japan (skip to last comment).

Prior to the formal standards work the Rubyspec project aimed to create an executable specification. As far as I can see this is akin to some of the tools I wrote about a few months ago.

IST/5, the committee at British Standards responsible for language standards is looking for UK people (people in other countries have to contact their national standards’ body) interested in getting involved with the Ruby ISO Standard’s work. I am a member of IST/5 and if you email me I will pass your contact details along to the chairman.

Recent Comments