Archive

Claiming that software is AI based is about to become expensive

The European Commission is updating the EU Machinery Directive, which covers the sale of machinery products within the EU. The updates include wording to deal with intelligent robots, and what the commission calls AI software (contained in machinery products).

The purpose of the initiative is to: “… (i) ensuring a high level of safety and protection for users of machinery and other people exposed to it; and (ii) establishing a high level of trust in digital innovative technologies for consumers and users, …”

What is AI software, and how is it different from non-AI software?

Answering these questions requires knowing what is, and is not, AI. The EU defines Artificial Intelligence as:

- ‘AI system’ means a system that is either software-based or embedded in hardware devices, and that displays behaviour simulating intelligence by, inter alia, collecting and processing data, analysing and interpreting its environment, and by taking action, with some degree of autonomy, to achieve specific goals;

- ‘autonomous’ means an AI system that operates by interpreting certain input, and by using a set of predetermined instructions, without being limited to such instructions, despite the system’s behaviour being constrained by and targeted at fulfilling the goal it was given and other relevant design choices made by its developer;

‘Simulating intelligence’ sounds reasonable, but actually just moves the problem on, to defining what is, or is not, intelligence. If intelligence is judged on an activity by activity bases, will self-driving cars be required to have the avoidance skills of a fly, while other activities might have to be on par with those of birds? There is a commission working document that defines: “Autonomous AI, or artificial super intelligence (ASI), is where AI surpasses human intelligence across all fields.”

The ‘autonomous’ component of the definition is so broad that it covers a wide range of programs that are not currently considered to be AI based.

The impact of the proposed update is that machinery products containing AI software are going to incur expensive conformance costs, which products containing non-AI software won’t have to pay.

Today it does not cost companies to claim that their systems are AI based. This will obviously change when a significant cost is involved. There is a parallel here with companies that used to claim that their beauty products provided medical benefits; the Federal Food and Drug Administration started requiring companies making such claims to submit their products to the new drug approval process (which is hideously expensive), companies switched to claiming their products provided “… the appearance of …”.

How are vendors likely to respond to the much higher costs involved in selling products that are considered to contain ‘AI software’?

Those involved in the development of products labelled as ‘safety critical’ try to prevent costs escalating by minimizing the amount of software treated as ‘safety critical’. Some of the arguments made for why some software is/is not considered safety critical can appear contrived (at least to me). It will be entertaining watching vendors, who once shouted “our products are AI based”, switching to arguing that only a tiny proportion of the code is actually AI based.

A mega-corp interested in having their ‘AI software’ adopted as an industry standard could fund the work necessary for the library/tool to be compliant with the EU directives. The cost of initial compliance might be within reach of smaller companies, but the cost of maintaining compliance as the product evolves is something that only a large company is likely to be able to afford.

The EU’s updating of its machinery directive is the first step towards formalising a legal definition of intelligence. Many years from now there will be a legal case that creates what later generation will consider to be the first legally accepted definition.

More men than women are incompetent/very competent

Womens’ rights campaigners are always making a big fuss about the huge impact equal rights/sex discrimination laws have had on increasing the career opportunities for very capable women to break the ‘glass ceiling’. The very capable end of the ability scale has always been sparsely populated and any significant impact is more likely to be noticeable in the less capable bands of the scale.

When I started out working in software development, if there was a women working on a team the chances were that she would be towards the very competent end of the scale (male/female ratio back then was what, 10/1?). These days, based on my limited experience, women are less likely to be competent but still a lot less likely, than men, to be completely incompetent.

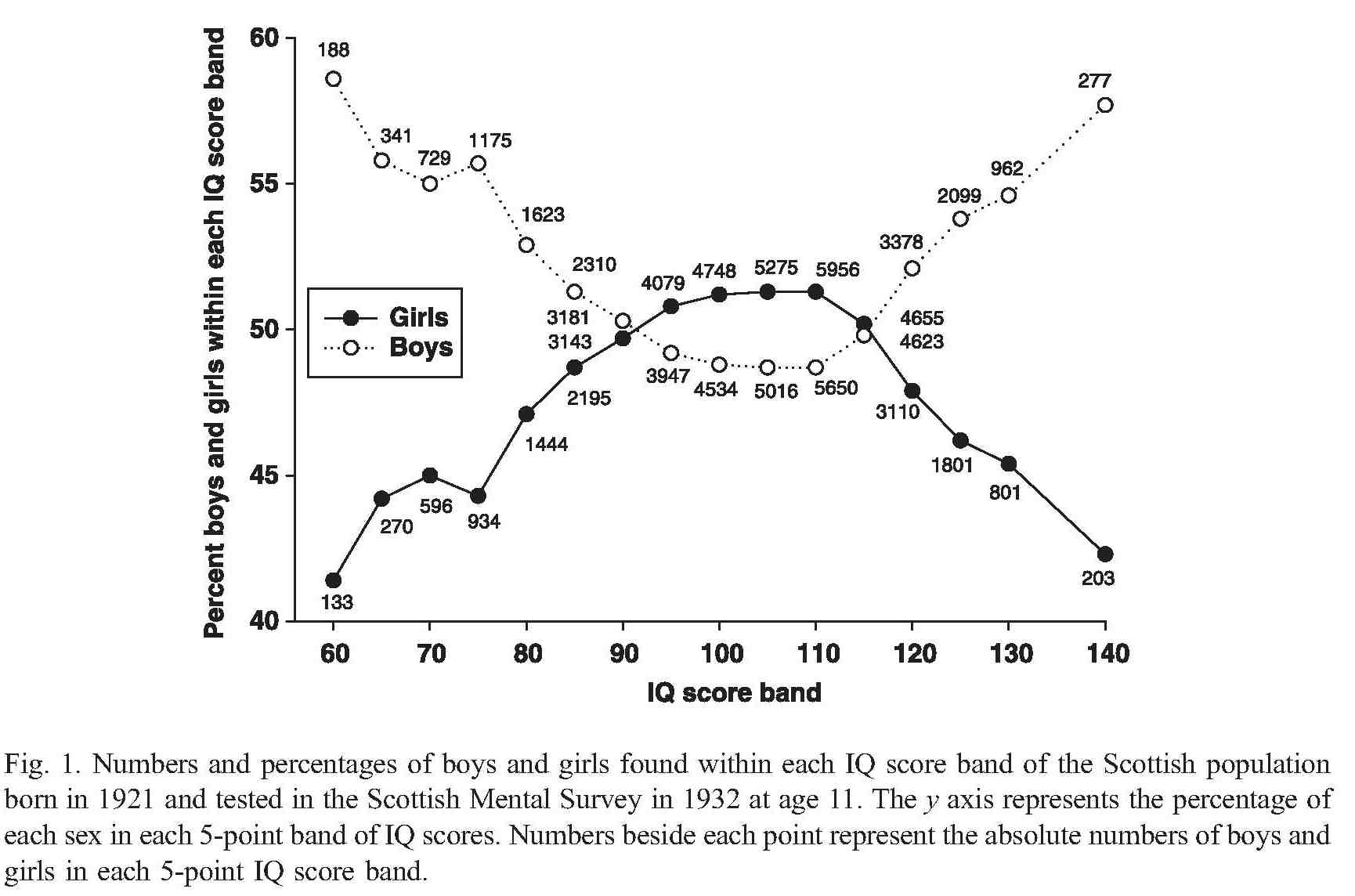

Based on my experience+talking to others it would appear that women are still underrepresented at the very competent/incompetent ends of the scale in software development. Why might this be (apart from being a sample size issue)? While the average value of male/female intelligence are the same (IQ tests are constructed to make them equal), the variance in IQ between the sexes is very different. The following is taken from Population sex differences in IQ at age 11: the Scottish mental survey 1932

The above plot provides a possible explanation for the prevalence of men at the very competent/incompetent ends of the scale and suggests that women should outnumber men in the middle, competent, band.

In practice there are still far fewer women than men working in software engineering, so a comparison using absolute counts is not possible; good luck running a survey covering software developer competence.

If the above IQ distribution carries over to competencies then it seems to me that those seeking to attract more women into software engineering, and engineering in general, should be targeting the more populous middle competence band and not the high fliers. Companies make a big fuss about wanting high fliers but in practice are often willing to take on people who are likely to be competent if they are the safer choice (that guy who appeared rather unusual during the interview may turn out to be flop rather than a rock star).

Recent Comments