Archive

The complexity of three assignment statements

Once I got into researching my book on C I was surprised at how few experiments had been run using professional software developers. I knew a number of people on the Association of C and C++ Users committee, in particular the then chair Francis Glassborow, and suggested that they ought to let me run an experiment at the 2003 ACCU conference. They agreed and I have been running an experiment every year since.

Before the 2003 conference I had never run an experiment that had people as subjects. I knew that if I wanted to obtain a meaningful result the number of factors that could vary had to be limited to as few as possible. I picked a topic which has probably been the subject of more experiments that any other topics, short term memory. The experimental design asked subjects to remember a list of three assignment statements (e.g., X = 5;), perform an unrelated task that was likely to occupy them for 10 seconds or so, and then recognize the variables they had previously seen within a list and recall the numeric value assigned to each variable.

I knew all about the factors that influenced memory performance for lists of words: word frequency, word-length, phonological similarity, how chunking was often used to help store/recall information and more. My variable names were carefully chosen to balance all of these effects and the information content of the three assignments required slightly more short term memory storage than subjects were likely to have.

The results showed none of the effects that I was expecting. Had I found evidence that a professional software developer’s brain really did operate differently than other peoples’ or was something wrong with my experiment? I tried again two years later (I ran a non-memory experiment the following year while I mulled over my failure) and this time a chance conversation with one of the subjects after the experiment uncovered one factor I had not controlled for.

Software developers are problem solvers (well at least the good ones are) and I had presented them with a problem; how to remember information that appeared to require more storage than available in their short term memories and accurately recall it shortly afterwards. The obvious solution was to reduce the amount of information that needed to be stored by simply remembering the first letter of every variable (which one of the effects I was controlling for had insured was unique) not the complete variable name.

I ran another experiment the following year and still did not obtain the expected results. What was I missing now? I don’t know and in 2008 I ran a non-memory based experiment. I still have no idea what techniques my subjects are using to remember information about three assignment statements that are preventing me getting the results I expect.

Perhaps those researchers out there that claim to understand the processes involved in comprehending a complete function definition can help me out by explaining the mental processes involved in remembering information about three assignment statements.

Measuring developer coding expertise

A common measure of developer experience is the number of years worked. The only good that can be said about this measure is that it is easy to calculate. Studies of experts in various fields have found that acquiring expertise requires a great deal of deliberate practice (10,000 hours is often quoted at the amount of practice put in by world class experts).

I think that coding expertise is acquired by reading and writing code, but I have little idea of the relative contributions made by reading and writing and whether reading the same code twice count twice or is there a law of diminishing returns on rereading code?

So how much code have developers read and written during their professional lives? Some projects have collected information on the number of ‘delivered’ lines of code written by developers over some time period. How many lines does a developer actually write for every line delivered (some functions may be rewritten several times while others may be deleted without every being making it into a final delivery)? Nobody knows. As for lines of code read, nobody has previously expressed an interest in collecting this kind of information.

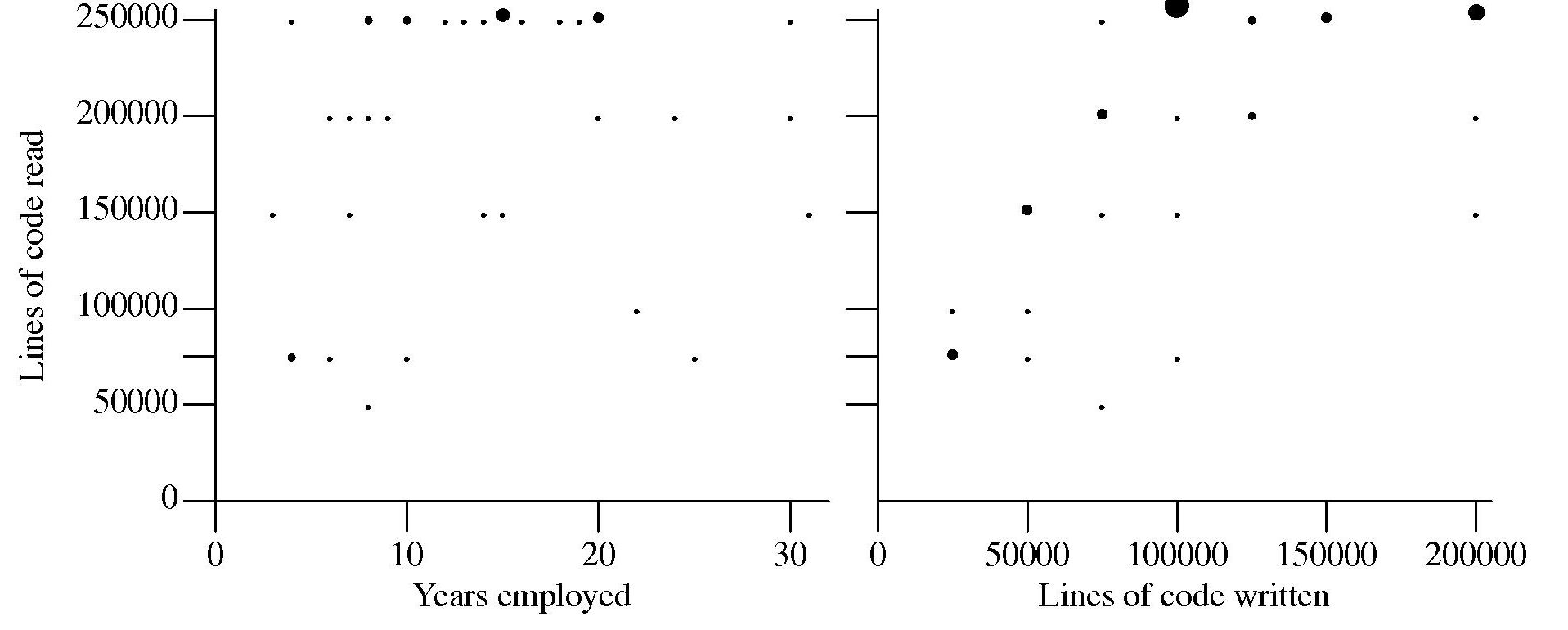

Some experiments, involving professional developers, I have run take as their starting point that developer performance improves with practice. Needing some idea of the amount of practice my subjects have had reading and writing code I asked them to tell me how much code they think they have read and written, as well as the number of years they have worked professionally in software development.

The answers given by my subjects were not very convincing:

Estimates of the ratio code read/written varied by more than five to one (the above graph suffers from a saturation problem for lines of code read, I had not provided a tick box that was greater than 250,000). I cannot complain, my subjects volunteered part of their lunch time to take part in an experiment and were asked to answer these questions while being given instructions on what they were being asked to do during the experiment.

I have asked this read/written question a number of times and received answers that exhibit similar amounts of uncertainty and unlikeliness. Thinking about it I’m not sure that giving subjects more time to answer this question would improve the accuracy of the answers. Very few developers monitor their own performance. The only reliable way of answering this question is by monitoring developer’s eye movements as they interact with code for some significant duration of time (preferably weeks).

Unobtrusive eye trackers may not be sufficiently accurate to provide a line-of-code level of resolution and the more accurate head mounted trackers are a bit intrusive. But given their price more discussion on this topic is currently of little value 🙁

Criteria for knowing a language

What does it mean for somebody to claim to know a computer language? In the commercial world it means the person is claiming to be capable of fluently (i.e., only using knowledge contained in their head and without having to unduly ponder) reading, and writing code in some generally accepted style applicable to that language. The academic world generally sets a much lower standard of competence (perhaps because most of its inhabitants leave before any significant expertise is acquired). If I had a penny for every recent graduate who claimed to know a language and was incapable of writing a program that read in a list of integers and printed their sum (I know companies that set tougher problems, but they do not seem to have higher failure rates), I would be a rich man.

One experiment asked 21 postgraduate and academic staff which of the following individuals they would regard as knowing Java:

The results were:

_ NO YES

A 21 0

B 18 3

C 16 5

D 8 13

E 0 21

These answers reflect the environment from which the subjects were drawn. When I wrote compilers for a living, I did not consider that anybody knew a language unless they had written a compiler for it, a point of view echoed by other compiler writers I knew.

I’m not sure that commercial developers would be happy with answer (E), in fact they could probably expand (E) into five separate questions that tested the degree to which a person was able to combine various elements of the language to create a meaningful whole. In the commercial world, stage (E) is where people are expected to start.

The criteria used to decide whether somebody knows a language depends on which group of people you talk to; academics, professional developers and compiler writers each have their own in-group standards. In a sense the question is irrelevant, a small amount of language knowledge applied well can be used to do a reasonable job of creating a program for most applications.

Unexpected experimental effects

The only way to find out the factors that effect developers’ source code performance is to carry out experiments where they are the subjects. Developer performance on even simple programming tasks can be effected by a large number of different factors. People are always surprised at the very small number of basic operations I ask developers to perform in the experiments I run. My reply is that only by minimizing the number of factors that might effect performance can I have any degree of certainty that the results for the factors I am interested in are reliable.

Even with what appear to be trivial tasks I am constantly surprised by the factors that need to be controlled. A good example is one of the first experiments I ever ran. I thought it would be a good idea to replicate, using a software development context, a widely studied and reliably replicated human psychological effect; when asked to learn and later recall/recognize a list of words people make mistakes. Psychologists study this problem because it provides a window into the operation structure of the human memory subsystem over short periods of time (of the order of at most tens of seconds). I wanted to find out what sort of mistakes developers would make when asked to remember information about a sequence of simple assignment statements (e.g.,

qbt = 6;).I carefully read the appropriate experimental papers and had created lists of variables that controlled for every significant factor (e.g., number of syllables, frequency of occurrence of the words in current English usage {performance is better for very common words}) and the list of assignment statements was sufficiently long that it would just overload the capacity of short term memory (about 2 seconds worth of sound).

The results contained none of the expected performance effects, so I ran the experiment again looking for different effects; nothing. A chance comment by one of the subjects after taking part in the experiment offered one reason why the expected performance effects had not been seen. By their nature developers are problem solvers and I had set them a problem that asked them to remember information involving a list of assignment statements that appeared to be beyond their short term memory capacity. Problem solvers naturally look for patterns and common cases and the variables in each of my carefully created list of assignment statements could all be distinguished by their first letter. Subjects did not need to remember the complete variable name, they just needed to remember the first letter (something I had not controlled for). Asking around I found that several other subjects had spotted and used the same strategy. My simple experiment was not simple enough!

I was recently reading about an experiment that investigated the factors that motivate developers to comment code. Subjects were given some code and asked to add additional functionality to it. Some subjects were given code containing lots of comments while others were given code containing few comments. The hypothesis was that developers were more likely to create comments in code that already contained lots of comments, and the results seemed to bear this out. However, closer examination of the answers showed that most subjects had cut and pasted chunks (i.e., code and comments) from the code they were given. So code the percentage of code in the problem answered mimicked that in the original code (in some cases subjects had complicated the situation by refactoring the code).