Archive

Modular vs. monolithic programs: a big performance difference

For a long time now I have been telling people that no experiment has found a situation where the treatment (e.g., use of a technique or tool) produces a performance difference that is larger than the performance difference between the subjects.

The usual results are that differences between people is the source of the largest performance difference, successive runs are the next largest (i.e., people get better with practice), and the smallest performance difference occurs between using/not using the technique or tool.

This is rather disheartening news.

While rummaging through a pile of books I had not looked at in many years, I (re)discovered the paper “An empirical study of the effects of modularity on program modifiability” by Korson and Vaishnavi, in “Empirical Studies of Programmers” (the first one in the series). It’s based on Korson’s 1988 PhD thesis, with the same title.

There were four experiments, involving seven people from industry and nine students, each involving modifying a 900(ish)-line program in some way. There were two versions of each program, they differed in that one was written in a modular form, while the other was monolithic. Subjects were permuted between various combinations of program version/problem, but all problems were solved in the same order.

The performance data (time to complete the task) was published in the paper, so I fitted various regressions models to it (code+data). There is enough information in the data to separate out the effects of modular/monolithic, kind of problem and subject differences. Because all subjects solved problems in the same order, it is not possible to extract the impact of learning on performance.

The modular/monolithic performance difference was around twice as large as the difference between subjects (removing two very poorly performing subjects reduces the difference to 1.5). I’m going to have to change my slides.

Would the performance difference have been so large if all the subjects had been experienced developers? There is not a lot of well written modular code out there, and so experienced developers get lots of practice with spaghetti code. But, even if the performance difference is of the same order as the difference between developers, that is still a very worthwhile difference.

Now there are lots of ways to write a program in modular form, and we don’t know what kind of job Korson did in creating, or locating, his modular programs.

There are also lots of ways of writing a monolithic program, some of them might be easy to modify, others a tangled mess. Were these programs intentionally written as spaghetti code, or was some effort put into making them easy to modify?

The good news from the Korson study is that there appears to be a technique that delivers larger performance improvements than the difference between people (replication needed). We can quibble over how modular a modular program needs to be, and how spaghetti-like a monolithic program has to be.

Impact of group size and practice on manual performance

How performance varies with group size is an interesting question that is still an unresearched area of software engineering. The impact of learning is also an interesting question and there has been some software engineering research in this area.

I recently read a very interesting study involving both group size and learning, and Jaakko Peltokorpi kindly sent me a copy of the data.

That is the good news; the not so good news is that the experiment was not about software engineering, but the manual assembly of a contraption of the experimenters devising. Still, this experiment is an example of the impact of group size and learning (through repeating the task) on time to complete a task.

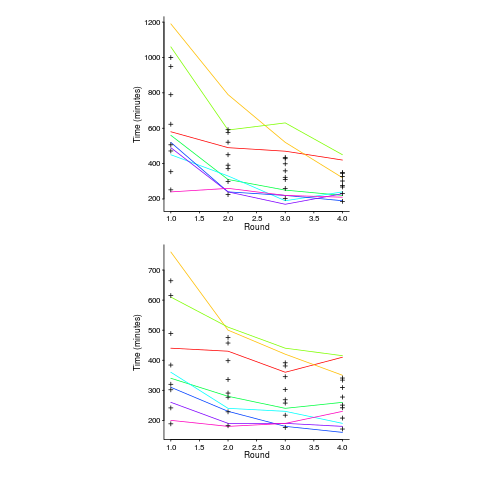

Subjects worked in groups of one to four people and repeated the task four times. Time taken to assemble a bespoke, floor standing rack with some odd-looking connections between components was measured (the image in the paper shows something that might function as a floor standing book-case, if shelves were added, apart from some component connections getting in the way).

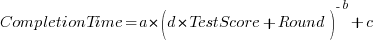

The following equation is a very good fit to the data (code+data). There is theory explaining why  applies, but the division by group-size was found by suck-it-and-see (in another post I found that time spent planning increased with teams size).

applies, but the division by group-size was found by suck-it-and-see (in another post I found that time spent planning increased with teams size).

There is a strong repetition/group-size interaction. As the group size increases, repetition has less of an impact on improving performance.

![time = 0.16+ 0.53/{group size} - log(repetitions)*[0.1 + {0.22}/{group size}] time = 0.16+ 0.53/{group size} - log(repetitions)*[0.1 + {0.22}/{group size}]](https://shape-of-code.com/wp-content/plugins/wpmathpub/phpmathpublisher/img/math_981_b0d171bba046801a68ce5dc8ae1d6115.png)

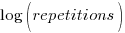

The following plot shows one way of looking at the data (larger groups take less time, but the difference declines with practice), lines are from the fitted regression model:

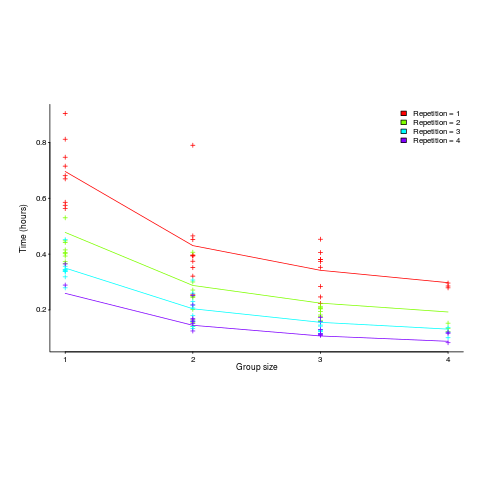

and here is another (a group of two is not twice as fast as a group of one; with practice smaller groups are converging on the performance of larger groups):

Would the same kind of equation fit the results from solving a software engineering task? Hopefully somebody will run an experiment to find out 🙂

Students vs. professionals in software engineering experiments

Experiments are an essential component of any engineering discipline. When the experiments involve people, as subjects in the experiment, it is crucial that the subjects are representative of the population of interest.

Academic researchers have easy access to students, but find it difficult to recruit professional developers, as subjects.

If the intent is to generalize the results of an experiment to the population of students, then using student as subjects sounds reasonable.

If the intent is to generalize the results of an experiment to the population of professional software developers, then using student as subjects is questionable.

What it is about students that makes them likely to be very poor subjects, to use in experiments designed to learn about the behavior and performance of professional software developers?

The difference between students and professionals is practice and experience. Professionals have spent many thousands of hours writing code, attending meetings discussing the development of software; they have many more experiences of the activities that occur during software development.

The hours of practice reading and writing code gives professional developers a fluency that enables them to concentrate on the problem being solved, not on technical coding details. Yes, there are students who have this level of fluency, but most have not spent the many hours of practice needed to achieve it.

Experience gives professional developers insight into what is unlikely to work and what may work. Without experience students have no way of evaluating the first idea that pops into their head, or a situation presented to them in an experiment.

People working in industry are well aware of the difference between students and professional developers. Every year a fresh batch of graduates start work in industry. The difference between a new graduate and one with a few years experience is apparent for all to see. And no, Masters and PhD students are often not much better and in some cases worse (their prolonged sojourn in academia means that have had more opportunity to pick up impractical habits).

It’s no wonder that people in industry laugh when they hear about the results from experiments based on student subjects.

Just because somebody has “software development” in their job title does not automatically make they an appropriate subject for an experiment targeting professional developers. There are plenty of managers with people skills and minimal technical skills (sub-student level in some cases)

In the software related experiments I have run, subjects were asked how many lines of code they had read/written. The low values started at 25,000 lines. The intent was for the results of the experiments to be generalized to the population of people who regularly wrote code.

Psychology journals are filled with experimental papers that used students as subjects. The intent is to generalize the results to the general population. It has been argued that students are not representative of the general population in that they have spent more time reading, writing and reasoning than most people. These subjects have been labeled as WEIRD.

I spend a lot of time reading software engineering papers. If a paper involves human subjects, the first thing I do is find out whether the subjects were students (usual) or professional developers (not common). Authors sometimes put effort into dressing up their student subjects as having professional experience (perhaps some of them have spent a year or two in industry, but talking to the authors often reveals that the professional experience was tutoring other students), others say almost nothing about the identity of the subjects. Papers describing experiments using professional developers, trumpet this fact in the abstract and throughout the paper.

I usually delete any paper using student subjects, some of the better ones are kept in a subdirectory called students.

Software engineering researchers are currently going through another bout of hand wringing over the use of student subjects. One paper makes the point that a student based experiment is a good way of validating an experiment that will later involve professional developers. This is a good point, but ignored the problem that researchers rarely move on to using professional subjects; many researchers only ever intend to run student-based experiments. Also, they publish the results from the student based experiment, which are at best misleading (but academics get credit for publishing papers, not for the content of the papers).

Researchers are complaining that reviews are rejecting their papers on student based experiments. I’m pleased to hear that reviewers are rejecting these papers.

Experimental Psychology by Robert S. Woodworth

I have just discovered “Experimental Psychology” by Robert S. Woodworth; first published in 1938, I have a reprinted in Great Britain copy from 1951. The Internet Archive has a copy of the 1954 revised edition; it’s a very useful pdf, but it does not have the atmospheric musty smell of an old book.

The Archives of Psychology was edited by Woodworth and contain reports of what look like ground breaking studies done in the 1930s.

The book is surprisingly modern, in that the topics covered are all of active interest today, in fields related to cognitive psychology. There are lots of experimental results (which always biases me towards really liking a book) and the coverage is extensive.

The history of cognitive psychology, as I understood it until this week, was early researchers asking questions, doing introspection and sometimes running experiments in the late 1800s and early 1900s (e.g., Wundt and Ebbinghaus), behaviorism dominants the field, behaviorism is eviscerated by Chomsky in the 1960s and cognitive psychology as we know it today takes off.

Now I know that lots of interesting and relevant experiments were being done in the 1920s and 1930s.

What is missing from this book? The most obvious omission is equations; lots of data points plotted on graph paper, but no attempt to fit an equation to anything, e.g., an exponential curve to the rate of learning.

A more subtle omission is the world view; digital computers had not been invented yet and Shannon’s information theory was almost 20 years in the future. Researchers tend to be heavily influenced by the tools they use and the zeitgeist. Computers as calculators and information processors could not be used as the basis for models of the human mind; they had not been invented yet.

Replication: not always worth the effort

Replication is the means by which mistakes get corrected in science. A researcher does an experiment and gets a particular result, but unknown to them one or more unmeasured factors (or just chance) had a significant impact. Another researcher does the same experiment and fails to get the same results, and eventually many experiments later people have figured out what is going on and what the actual answer is.

In practice replication has become a low status activity, journals want to publish papers containing new results, not papers backing up or refuting the results of previously published papers. The dearth of replication has led to questions being raised about large swathes of published results. Most journals only published papers that contain positive results, i.e., something was shown to some level of statistical significance; only publishing positive results produces publication bias (there have been calls for journals that publishes negative results).

Sometimes, repeating an experiment does not seem worth the effort. One such example is: An Explicit Strategy to Scaffold Novice Program Tracing. It looks like the authors ran a proper experiment and did everything they are supposed to do; but, I think the reason that got a positive result was luck.

The experiment involved 24 subjects and these were randomly assigned to one of two groups. Looking at the results (figures 4 and 5), it appears that two of the subjects had much lower ability that the other subjects (the authors did discuss the performance of these two subjects). Both of these subjects were assigned to the control group (there is a 25% chance of this happening, but nobody knew what the situation was until the experiment was run), pulling down the average of the control, making the other (strategy) group appear to show an improvement (i.e., the teaching strategy improved student performance).

Had one, or both, low performers been assigned to the other (strategy) group, no experimental effect would have shown up in the results, significantly reducing the probability that the paper would have been accepted for publication.

Why did the authors submit the paper for publication? Well, academic performance is based on papers published (quality of journal they appear in, number of citations, etc), a positive result is reason enough to submit for publication. The researchers did what they have been incentivized to do.

I hope the authors of the paper continue with their experiments. Life is full of chance effects and the only way to get a solid result is to keep on trying.

Experimental method for measuring benefits of identifier naming

I was recently came across a very interesting experiment in Eran Avidan’s Master’s thesis. Regular readers will know of my interest in identifiers; while everybody agrees that identifier names have a significant impact on the effort needed to understand code, reliably measuring this impact has proven to be very difficult.

The experimental method looked like it would have some impact on subject performance, but I was not expecting a huge impact. Avidan’s advisor was Dror Feitelson, who kindly provided the experimental data, answered my questions and provided useful background information (Dror is also very interested in empirical work and provides a pdf of his book+data on workload modeling).

Avidan’s asked subjects to figure out what a particular method did, timing how long it took for them to work this out. In the control condition a subject saw the original method and in the experimental condition the method name was replaced by local and parameter names were replaced by single letter identifiers; in all cases the method name was replaced by xxx andxxx. The hypothesis was that subjects would take longer for methods modified to use ‘random’ identifier names.

A wonderfully simple idea that does not involve a lot of experimental overhead and ought to be runnable under a wide variety of conditions, plus the difference in performance is very noticeable.

The think aloud protocol was used, i.e., subjects were asked to speak their thoughts as they processed the code. Having to do this will slow people down, but has the advantage of helping to ensure that a subject really does understand the code. An overall slower response time is not important because we are interested in differences in performance.

Each of the nine subjects sequentially processed six methods, with the methods randomly assigned as controls or experimental treatments (of which there were two, locals first and parameters first).

The procedure, when a subject saw a modified method was as follows: the subject was asked to explain the method’s purpose, once an answer was given (or 10 mins had elapsed) either the local or parameter names were revealed and the subject had to again explain the method’s purpose, and when an answer was given the names of both locals and parameters was revealed and a final answer recorded. The time taken for the subject to give a correct answer was recorded.

The summary output of a model fitted using a mixed-effects model is at the end of this post (code+data; original experimental materials). There are only enough measurements to have subject as a random effect on the treatment; no order of presentation data is available to look for learning effects.

Subjects took longer for modified methods. When parameters were revealed first, subjects were 268 seconds slower (on average), and when locals were revealed first 342 seconds slower (the standard deviation of the between subject differences was 187 and 253 seconds, respectively; less than the treatment effect, surprising, perhaps a consequence of information being progressively revealed helping the slower performers).

Why is subject performance less slow when parameter names are revealed first? My thoughts: parameter names (if well-chosen) provide clues about what incoming values represent, useful information for figuring out what a method does. Locals are somewhat self-referential in that they hold local information, often derived from parameters as initial values.

What other factors could impact subject performance?

The number of occurrences of each name in the body of the method provides an opportunity to deduce information; so I think time to figure out what the method does should less when there are many uses of locals/parameters, compared to when there are few.

The ability of subjects to recognize what the code does is also important, i.e., subject code reading experience.

There are lots of interesting possibilities that can be investigated using this low cost technique.

Linear mixed model fit by REML ['lmerMod']

Formula: response ~ func + treatment + (treatment | subject)

Data: idxx

REML criterion at convergence: 537.8

Scaled residuals:

Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

-1.34985 -0.56113 -0.05058 0.60747 2.15960

Random effects:

Groups Name Variance Std.Dev. Corr

subject (Intercept) 38748 196.8

treatmentlocals first 64163 253.3 -0.96

treatmentparameters first 34810 186.6 -1.00 0.95

Residual 43187 207.8

Number of obs: 46, groups: subject, 9

Fixed effects:

Estimate Std. Error t value

(Intercept) 799.0 110.2 7.248

funcindexOfAny -254.9 126.7 -2.011

funcrepeat -560.1 135.6 -4.132

funcreplaceChars -397.6 126.6 -3.140

funcreverse -466.7 123.5 -3.779

funcsubstringBetween -145.8 125.8 -1.159

treatmentlocals first 342.5 124.8 2.745

treatmentparameters first 267.8 106.0 2.525

Correlation of Fixed Effects:

(Intr) fncnOA fncrpt fncrpC fncrvr fncsbB trtmntlf

fncndxOfAny -0.524

funcrepeat -0.490 0.613

fncrplcChrs -0.526 0.657 0.620

funcreverse -0.510 0.651 0.638 0.656

fncsbstrngB -0.523 0.655 0.607 0.655 0.648

trtmntlclsf -0.505 -0.167 -0.182 -0.160 -0.212 -0.128

trtmntprmtf -0.495 -0.184 -0.162 -0.184 -0.228 -0.213 0.673 |

Experiment, replicate, replicate, replicate,…

Popular science writing often talks about how one experiment proved this-or-that theory or disproved ‘existing theories’. In practice, it takes a lot more than one experiment before people are willing to accept a new theory or drop an existing theory. Many, many experiments are involved, but things need to be simplified for a popular audience and so one experiment emerges to represent the pivotal moment.

The idea of one experiment being enough to validate a theory has seeped into the world view of software engineering (and perhaps other domains as well). This thinking is evident in articles where one experiment is cited as proof for this-or-that and I am regularly asked what recommendations can be extracted from the results discussed in my empirical software book (which contains very few replications, because they rarely exist). This is a very wrong.

A statistically significant experimental result is a positive signal that the measured behavior might be real. The space of possible experiments is vast and any signal that narrows the search space is very welcome. Multiple replication, by others and with variations on the experimental conditions (to gain an understanding of limits/boundaries), are needed first to provide confidence the behavior is repeatable and then to provide data for building practical models.

Psychology is currently going through a replication crisis. The incentive structure for researchers is not to replicate and for journals not to publish replications. The Reproducibility Project is doing some amazing work.

Software engineering has had an experiment problem for decades (the problem is lack of experiments), but this is slowly starting to change. A replication problem is in the future.

Single experiments do have uses other than helping to build a case for a theory. They can be useful in ruling out proposed theories; results that are very different from those predicted can require ideas to be substantially modified or thrown away.

In the short term (i.e., at least the next five years) the benefit of experiments is in ruling out possibilities, as well as providing general pointers to the possible shape of things. Theories backed by substantial replications are many years away.

Ability to remember code improves with experience

What mental abilities separate an expert from a beginner?

In the 1940s de Groot studied expertise in Chess. Players were shown a chess board containing various pieces and then asked to recall the locations of the pieces. When the location of the chess pieces was consistent with a likely game, experts significantly outperformed beginners in correct recall of piece location, but when the pieces were placed at random there was little difference in recall performance between experts and beginners. Also players having the rank of Master were able to reconstruct the positions almost perfectly after viewing the board for just 5 seconds; a recall performance that dropped off sharply with chess ranking.

The interpretation of these results (which have been duplicated in other areas) is that experts have learned how to process and organize information (in their field) as chunks, allowing them to meaningfully structure and interpret board positions; beginners don’t have this ability to organize information and are forced to remember individual pieces.

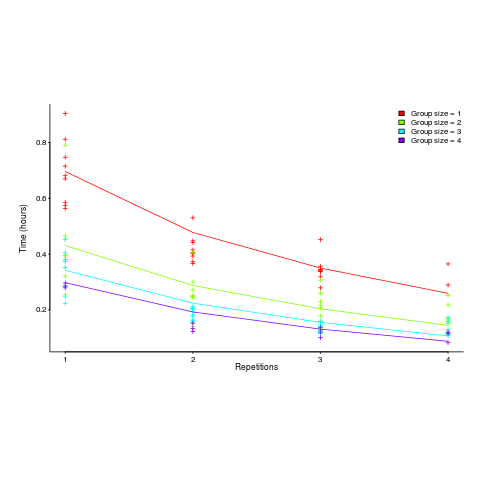

In 1981 McKeithen, Reitman, Rueter and Hirtle repeated this experiment, but this time using 31 lines of code and programmers of various skill levels. Subjects were given two minutes to study 31 lines of code, followed by three minutes to write (on a blank sheet of paper) all the code they could recall; this process was repeated five times (for the same code). The plot below shows the number of lines correctly recalled by experts (2,000+ hours programming experience), intermediates (just finished programming course) and beginners (just started programming course), left performance using ‘normal’ code and right is performance viewing code created by randomizing lines from ‘normal’ code; only the mean values in each category are available (code+data):

Experts start off remembering more than beginners and their performance improves faster with practice.

Compared to the Power law of practice (where experts should not get a lot better, but beginners should improve a lot), this technique is a much less time consuming way of telling if somebody is an expert or beginner; it also has the advantage of not requiring any application domain knowledge.

If you have 30 minutes to spare, why not test your ‘expertise’ on this code (the .c file, not the .R file that plotted the figure above). It’s 40 odd lines of C from the Linux kernel. I picked C because people who know C++, Java, PHP, etc should have no trouble using existing skills to remember it. What to do:

- You need five blank sheets of paper, a pen, a timer and a way of viewing/not viewing the code,

- view the code for 2 minutes,

- spend 3 minutes writing down what you remember on a clean sheet of paper,

- repeat until done 5 times.

Count how many lines you correctly wrote down for each iteration (let’s not get too fussed about exact indentation when comparing) and send these counts to me (derek at the primary domain used for this blog), plus some basic information on your experience (say years coding in language X, years in Y). It’s anonymous, so don’t include any identifying information.

I will wait a few weeks and then write up the data o this blog, as well as sharing the data.

Update: The first bug in the experiment has been reported. It takes longer than 3 minutes to write out all the code. Options are to stick with the 3 minutes or to spend more time writing. I will leave the choice up to you. In a test situation, maximum time is likely to be fixed, but if you have the time and want to find out how much you remember, go for it.

Power law of practice in software implementation

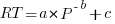

People get better with practice. The power law of practice specifies  , where:

, where:  is the response time,

is the response time,  the amount of practice and

the amount of practice and  ,

,  and

and  are constants. However, sometimes an exponential equation is a better fit for to the data:

are constants. However, sometimes an exponential equation is a better fit for to the data:  . There are theoretical reasons for liking a power law (e.g., it can be derived from the chunking of information), but it is difficult to argue with the exponential fitting so much data better than a power law.

. There are theoretical reasons for liking a power law (e.g., it can be derived from the chunking of information), but it is difficult to argue with the exponential fitting so much data better than a power law.

The plot below, from a study by Alteneder, shows the time taken to solve the same jig-saw puzzle, for 35 trials (red); followed by a two week pause and another 35 trials (in blue; if anybody else wants to try this, a dedicated weekend should be long enough to complete over 20 trials). The lines are fitted power law and exponential equations (code+data). Can you tell which is which?

To find out if the same behavior occurs with software we need data on developers implementing the identical applications multiple times. I know of two experiments where the same application has been implemented multiple times by the same people, and where the data is available. Please let me know if you know of any others.

Zislis timed himself implementing 12 algorithms from the CACM collection in each of three languages, iterating four times (my copy came from the Purdue library, which as I write this is not listing the report). The large number of different programs implemented, coupled with the use of multiple languages, makes it difficult to separate out learning effects.

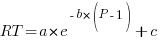

Lui and Chan ran an experiment where 24 developers (8 pairs {pair programming} and 8 singles) implemented the same application four times. The plot below shows the time taken to complete each implementation (singles top, pairs bottom, with black cross showing predictions made by a power law fit).

Different subjects start the experiment with different amounts of ability and past experience. Before starting, subjects took a multiple choice test of their knowledge. If we take the results of this test as a proxy for the ability/knowledge at the start of the experiment, then the power law equation becomes (a similar modification can be made to the exponential equation):

That is, the test score is treated as equivalent to performing some number of rounds of implementation). A power law is a better fit than exponential to this data (code+data); the fit captures the general shape, but misses lots of what look like important details.

The experiment was run over successive weekends. So there was opportunity for some forgetting to occur during the week days, and the amount forgotten will vary between people. It is easy to think of other issues that could have influenced subject performance.

This experiment must rank as one of the most interesting software engineering experiments performed to date.

Least Recently Used: The experiment that made its reputation

Today we all know that least recently used is the best page replacement algorithm for virtual memory systems (actually paging is complicated in today’s intertwined computing world).

Virtual memory was invented in 1959 and researchers spent the 1960s trying to figure out the best page replacement algorithm.

Programs were believed to spend most of their time in loops and this formed the basis for the rationale for why FIFO, First In First Out, was the best page replacement algorithm (widely used at the time).

Least recently used, LRU, was on people’s radar as a possible technique and was mathematically analysed, along with various other techniques. The optimal technique was known and given the name OPT; a beautifully simple technique with one implementation drawback, it required knowledge of future memory usage behavior (needless to say some researchers set to work trying to predict future memory usage, so this algorithm could be used).

An experiment by Tsao, Comeau and Margolin, published in 1972, showed that LRU outperformed FIFO and random replacement. The rest, as they say, is history; in this case almost completely forgotten history.

The paper “A multifactor paging experiment: I. The experiment and conclusions” was published as one of a collection of papers in “Statistical Computer Performance Evaluation” edited by Freiberger. A second paper by two of the authors in the same book outlines the statistical methodology. Appearing in a book means this paper can be very hard to track down. I recently bought a copy of the book on Amazon for one penny (the postage was £2.80).

The paper contains a copy of the experimental results and below are the page swap numbers:

loadseq group group group freq freq freq alpha alpha alpha Pages 24 20 16 24 20 16 24 20 16 LRU S 32 48 538 52 244 998 59 536 1348 LRU M 53 81 1901 112 776 3621 121 1879 4639 LRU L 142 197 5689 262 2625 10012 980 5698 12880 FIFO S 49 67 789 79 390 1373 85 814 1693 FIFO M 100 134 3152 164 1255 4912 206 3394 5838 FIFO L 233 350 9100 458 3688 13531 1633 10022 17117 RAND S 62 100 1103 111 480 1782 111 839 2190 RAND M 96 245 3807 237 1502 6007 286 3092 7654 RAND L 265 2012 12429 517 4870 18602 1728 8834 23134 |

Three Fortran programs were used, Small (55 statements), Medium (215 statements) and Large (595 statements). These programs were loaded by group (sequences of frequently called subroutines grouped together), freq (subrotines causing the most page swaps were grouped together), alpha (subroutines were grouped alphabetically).

The system was configured with either 24, 20 or 16 pages of 4,096 bytes; it had a total of 256K of memory (a lot of memory back then). The experiment consumed 60 cpu hours.

Looking at the table, it is easy to see that LRU has the best performance. In places random replacement beats FIFO. A regression model (code and data) puts numbers on the performance advantage.

The paper says that the only interaction was between memory size (i.e., number of pages) and how the programs were loaded. I found pairwise interaction between all variables, but then I am using a technique that was being invented as this paper was being published (see code for details).

Number of page swaps was one of three techniques used for measuring performed. The other two were activity count (average number of pages in main memory referenced at least once between page swaps) and inactivity count (average time, measured in page swaps, of a page in secondary storage after it had been swapped out). See data for details.

I vividly remember dropping in on a randomly chosen lecture in computer science in the mid-70s (I studied physics and electronics), the subject was page selection algorithms and there were probably only a dozen people in the room (physics and electronics sometimes had close to 100). The lecturer regaled those present with how surprising it was that LRU was the best and somebody had actually done an experiment showing this. Having a physics/electronics background, the experimental approach to settling questions was second nature to me.

Recent Comments