Archive

The dark-age of software engineering research: some evidence

Looking back, the 1970s appear to be a golden age of software engineering research, with the following decades being the dark ages (i.e., vanity research promoted by ego and bluster), from which we are slowly emerging (a rough timeline).

Lots of evidence-based software engineering research was done in the 1970s, relative to the number of papers published, and I have previously written about the quantity of research done at Rome and the rise of ego and bluster after its fall (Air Force officers studying for a Master’s degree publish as much software engineering data as software engineering academics combined during the 1970s and the next two decades).

What is the evidence for a software engineering research dark ages, starting in the 1980s?

One indicator is the extent to which ancient books are still venerated, and the wisdom of the ancients is still regularly cited.

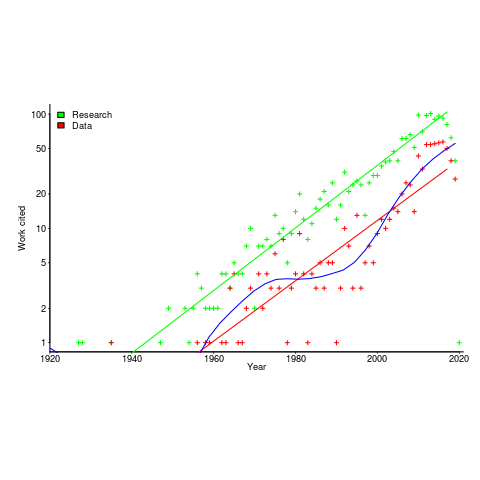

I claim that my evidence-based software engineering book contains all the useful publicly available software engineering data. The plot below shows the number of papers cited (green) and data available (red), per year; with fitted exponential regression models, and a piecewise regression fit to the data (blue) (code+data).

The citations+date include works that are not written by people involved in software engineering research, e.g., psychology, economics and ecology. For the time being I’m assuming that these non-software engineering researchers contribute a fixed percentage per year (the BibTeX file is available if anybody wants to do the break-down)

The two straight line fits are roughly parallel, and show an exponential growth over the years.

The piecewise regression (blue, loess was used) shows that the rate of growth in research data leveled-off in the late 1970s and only started to pick up again in the 1990s.

The dip in counts during the last few years is likely to be the result of me not having yet located all the recent empirical research.

Citation patterns in my two books

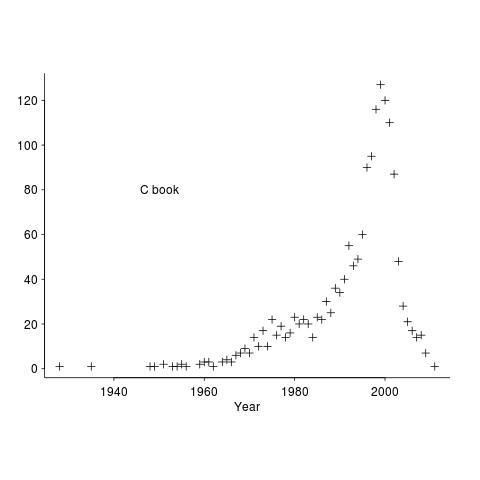

When writing my C book, I cited any paper or book whose material I made use of and/or that I thought would be useful to the reader. One of the rules for academic papers is to cite the paper that ‘invented’ the idea; this is intended to incentivize researchers to work hard to discover new things that will be cited many times (citation count is a measure of the importance of the work and these days a metric used when deciding promotions and awarding grants).

When I started writing the C book the premier search engine was AltaVista, with Google becoming number one a few years before the book was completed. Finding papers online was still a wondrous experience and Citeseer was a godsend.

The plot below shows the numbers of works cited by year of publication, for the C book.

These days all the information we could possible need is said to be online. I don’t think this is true, but it might be a good enough approximation. But being online does not mean being available for free, a lot of academic papers remain behind paywalls.

It used to be possible to visit a good University library and copy papers of interest (I have a filing cabinet full of paper from the C book). Those days are gone, with libraries moving their reference stock off-site (the better ones offer on-premise online access).

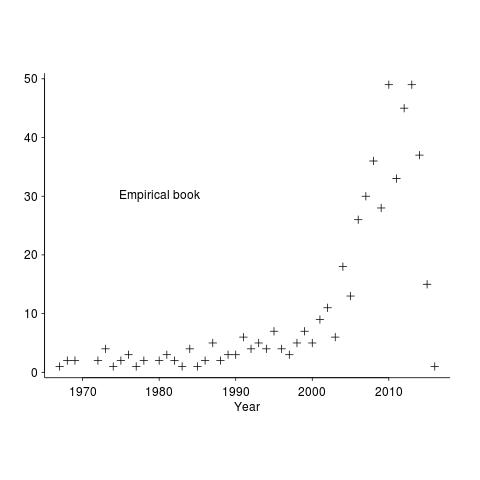

My book on empirical software engineering is driven by what data is available, which means most cited work is going to be relatively new. There is another big factor driving the work I cite this time around; I am fed up with tax payer funded research ending up behind paywalls, so I am only citing papers that can be downloaded for free (in practice they also have to be found by a search engine or linked to from somewhere or other) and when the ‘discovery’ paper is not available for download I cite a later work that is.

The plot below shows the numbers of works cited by year of publication, for the empirical software engineering draft book.

The rising slope is much sharper for the latest book. I think most of the difference is driven by the newness of the subject, software researchers tend to be very good (at least the non-business department ones) at making pdfs available for download.

Another factor might be how Citeseer and Google Scholar cross reference papers; Citeseer links to works cited by a paper (i.e., link back in time), while Google Scholar links to works that cite the paper (i.e., link forward in time).

Recent Comments