Archive

Christmas books for 2025

My rate of book reading has remained steady this year, however, my ability to buy really interesting books has declined. Consequently, the list of honourable mentions is longer than the main list. Hopefully my luck/skill will improve next year. As is usually the case, most book were not published in this year.

Liberal Fascism: The secret history of the Left from Mussolini to the Politics of Meaning by Jonah Goldberg is reviewed in a separate post.

Oxygen: The molecule that made the world by Nick Lane, a professor of evolutionary biochemistry, published in 2016. The book discusses changes in the percentage of oxygen in the Earth’s atmosphere over billions of years and the factors that are thought to have driven these changes. The content is at the technical end of popular science writing. The author is a strong proponent that life (which over a billion or so years produced most of the oxygen in the atmosphere) originated in hydrothermal vents, not via lightening storms in the Earth’s primordial atmosphere (as suggested by the Miller–Urey experiment). The Wikipedia article on the origins of life contains a lot more words on the Miller–Urey experiment.

“By the Numbers: Numeracy, Religion and the Quantitative Transformation of Early Modern England” by Jessica Marie Otis, a professor of history, published in 2024. Here, early modern England starts around 1543 with the publication of an arithmetic textbook, The Ground of Artes, that was republished 45 times up until 1700. As the title suggests, the book discusses the factors driving the spread of numeracy into the general population, e.g., the need for traders and organizations to keep accounts, and the people to keep track of time. For the general reader, the book is rather short at 160 readable pages. Historians get to enjoy the 51 pages of notes and 37 pages of bibliography.

For insightful long, discursive book reviews that are often more interesting than the books themselves (based on those I have purchased), see: Mr. and Mrs. Psmith’s Bookshelf. This year, Astral Codex ran a Non-Book Review Contest.

The blog Worshipping the Future by Helen Dale and Lorenzo Warby continues to be an excellent read. It is “… a series of essays dissecting the social mechanisms that have led to the strange and disorienting times in which we live.” The series is a well written analysis that attempts to “… understand mechanisms of how and the why, …” of Woke.

As an aside, one of the few pop cds I bought this year turned out to be excellent: “PARANOÏA, ANGELS, TRUE LOVE” by Christine and the Queens.

Honourable mentions

The Knowledge: How to Rebuild Our World from Scratch by Lewis Dartnell, an astrobiologist. Assuming you are among the approximately 5% of people still alive after civilizations collapses (the book does not talk about this, but without industrial scale production of food, most people will starve to death), how can useful modern day items (i.e., available in the last hundred years or so) be created? Items include ammonia-based fertilizer, electricity, radio receiver and simple drugs. The processes sound a lot easier to do than they are likely to be in practice (manufacturing processes invariably make use of a lot of tacit knowledge), but then it is a popular book covering a lot of ground. It’s really a list of items to consider, along with some starting ideas.

“Goodbye, Eastern Europe: An Intimate History of a Divided Land” by Jacob Mikanowski, a historian and science writer, published in 2023. A history of Eastern Europe from the first century to today, covering the countries encircled by Germany, the Baltic Sea, Russia, and the Black Sea/Mediterranean. The story is essentially one of migrations, and mass slaughters, with the accompanying creation and destruction of cultures. Harrowing in places. It’s no wonder that the people from that part of the world cling to whatever roots they have.

“Reframe Your Brain: The User Interface for Happiness and Success” by Scott Adams of Dilbert fame, published in 2023. To quote Wikipedia: “Cognitive reframing is a psychological technique that consists of identifying and then changing the way situations, experiences, events, ideas and emotions are viewed.” This book contains around 200 reframes of every day situations/events/emotions, with accompanying discussion. Some struck me as a bit outlandish, but sometimes outlandish has the desired effect.

Details on your best books of the year very welcome in the comments.

Christmas books for 2024

My rate of book reading has picked up significantly this year. The following are the really interesting books I read, as is usually the case, most were not published in this year.

I have enjoyed Grayson Perry’s TV programs on the art world, so I bought his book “Playing to the Gallery: Helping Contemporary Art in its Struggle to Be Understood“. It’s a fun, mischievous look at the art world by somebody working as a traditional artist, in the sense of creating work that they believe means/says something, rather than works that are only considered art because they are displayed in an art gallery.

“The Computer from Pascal to von Neumann” by H. H. Goldstine. This history of computing from the mid-1600s (the time of Blaise Pascal) to the mid-1900s (von Neumann died in 1957) told by a mathematician who was first involved in calculating artillery firing tables during World War II, and then worked with early computers and von Neumann. This book is full of insights that only a technical person could provide and is a joy to read.

I saw a poster advertising a guided tour of the trees in my local park, organized by Trees for Cities. It was a very interesting lunchtime; I had not appreciated how many different trees were growing there, including three different kinds of Oak tree. Trees for Cities run events all over the UK, and abroad. Of course, I had to buy some books to improve my tree recognition skills. I found “Collins tree guide” by O. Johnson and D. More to be the most useful and full of information. Various organizations have created maps of trees in cities around the world. The London Tree Map shows the location and species information for over 880,000 of trees growing on streets (not parks), New York also has a map. For a general analysis of patterns of tree growth, see “How to Read a Tree” by T. Gooley.

“Medieval Horizons: Why the Middle Ages Matter” by I. Mortimer. This book takes the reader through the social, cultural and economic changes that happened in England during the Middle Ages, which the author specifies as the period 1000 to 1600. I knew that many people were surfs, but did not know that slaves accounted for around 10% of the population, dropping to zero percent during this period. Changes, at least for the well-off, included moving from living in longhouses to living in what we would call a house, art works moved from two-dimensional representations to life-like images (e.g., renaissance quality), printing enables an explosion of books, non-poor people travelled more, ate better, and individualism started to take-off.

Statistical Consequences of Fat Tails: Real World Preasymptotics, Epistemology, and Applications by N. N. Taleb is a mathematically dense book (while the pdf is in color, I was disappointed that the printed version is black/white; this is the one I read while travelling). This book tells you a lot more than you need to know about the consequences of fat tail distributions. Why might you be interested in the problems of fat tails? Taleb starts by showing how little noise it takes for the comforting assumptions implied by the Normal/Gaussian distribution to fly out the window. The primary comforting assumptions are that the mean and variance of a small sample are representative of the larger population. A world of fat tail distributions is one where the unexpected is to be expected, where a single event can wipe out an organization or industry (banks are said to have lost more in the 2008 financial crisis than they had made in the previous many decades). This book is hard going, and I kept at it to get a feel for the answers to some of the objections to the bad news conveyed. There are a couple of places where I should have been more circumspect in my Evidence-based software engineering book.

I have previously reviewed General Relativity: The Theoretical Minimum by Susskind and Cabannes.

“Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II” by John W. Dower describes in harrowing detail the dire circumstances of the population of Japan immediately after World War II and what they had to endure to survive.

For more detailed book reviews, see: Mr. and Mrs. Psmith’s Bookshelf with some excellent and insightful long book reviews, and the annual Astral Codex Ten book review contest usually has a few excellent reviews/books.

For those of you who think that civilization is about to collapse, or at least like talking about the possibility, a reading list. At the practical level, I think sword fighting and archery skills are more likely to be useful in the longer term.

Christmas books for 2023

This year’s Christmas book list, based on what I read this year, and for the first time including a blog series that I’m sure will eventually appear in book form.

“To Explain the World: The discovery of modern science” by Steven Weinberg, 2015. Unless you know that Steven Weinberg won a physics Nobel prize, this looks like just another history of science book (the preface tells us that he also taught a history of science course for over a decade). This book is written by a scientist who appears to have read the original material (I’m assuming in translation), who puts the discoveries and the scientists involved at the center of the discussion; this is not the usual historian who sprinkles in a bit about science, while discussing the cast of period characters. For instance, I had never understood why the work of Galileo was considered to be so important (almost as a footnote, historians list a few discoveries of his). Weinberg devotes pages to discussing Galileo’s many discoveries (his mathematics was a big behind the times, continuing to use a geometric approach, rather than the newer algebraic techniques), and I now have a good appreciation of why Galileo is rated so highly by scientists down the ages.

Chapter 2 of “When Old Technologies Were New: Thinking about electric communication in the late nineteenth century” by Carolyn Marvin, 1988. The book is worth buying just for chapter 2, which contains many hilarious examples of how the newly introduced telephone threw a spanner in to the workings of the social etiquette of the class of person who could afford to install one. Suitors could talk to daughters without other family members being present, public phone booths allowed any class of person to be connected directly to the man of the house, and when phone companies started publishing publicly available directories containing subscriber name/address/number, WELL!?! In the US there were 1 million telephones installed by 1899, and subscribers were sometimes able to listen to live musical concerts and sports events (commercial radio broadcasting did not start until the 1920s).

“The Grand Strategy of the Roman Empire: From the first century A.D. to the third” by Edward Luttwak, 1976; h/t Mr. and Mrs. Psmith’s review. I cannot improve or add to John Psmith’s review. The book contains more details; the review captures the essence. On a related note, for the hard core data scientists out there: Early Imperial Roman army campaigning: observations on marching metrics, energy expenditure and the building of marching camps.

“Innovation and Market Structure: Lessons from the computer and semiconductor industries” by Nancy S. Dorfman, 1987. An economic perspective on the business of making and selling computers, from the mid-1940s to the mid-1980s. Lots of insights, (some) data, and specific examples (for the most part, the historians of computing are, well, historians who can craft a good narrative, but the insights are often lacking). The references led me to: Mancke, Fisher, and McKie, who condensed the 100K+ pages of trial transcript from the 1969–1982 IBM antitrust trial down to 1,500+ pages of Historical narrative.

Worshipping the Future by Helen Dale and Lorenzo Warby. Is “… a series of essays dissecting the social mechanisms that have led to the strange and disorienting times in which we live.” The series is a well written analysis that attempts to “… understand mechanisms of how and the why, …” of Woke.

Honourable mentions

“The Big Con: The story of the confidence man and the confidence trick” by David W. Maurer (source material for the film The Sting).

“Cubed: A secret history of the workplace” by Nikil Saval.

Christmas books for 2022

This year’s list of books for Christmas, or Isaac Newton’s birthday (in the Julian calendar in use when he was born), returns to its former length, and even includes a book published this year. My book Evidence-based Software Engineering also became available in paperback form this year, and would look great on somebodies’ desk.

The Mars Project by Wernher von Braun, first published in 1953, is a 91-page high-level technical specification for an expedition to Mars (calculated by one man and his slide-rule). The subjects include the orbital mechanics of travelling between Earth and Mars, the complications of using a planet’s atmosphere to slow down the landing craft without burning up, and the design of the spaceships and rockets (the bulk of the material). The one subject not covered is cost; von Braun’s estimated 950 launches of heavy-lift launch vehicles, to send a fleet of ten spacecraft with 70 crew, will not be cheap. I’ve no idea what today’s numbers might be.

The Fabric of Civilization: How textiles made the world by Virginia Postrel is a popular book full of interesting facts about the economic and cultural significance of something we take for granted today (or at least I did). For instance, Viking sails took longer to make than the ships they powered, and spinning the wool for the sails on King Canute‘s North Sea fleet required around 10,000 work years.

Wyclif’s Dust: Western Cultures from the Printing Press to the Present by David High-Jones is covered in an earlier post.

The Second World Wars: How the First Global Conflict Was Fought and Won by Victor Davis Hanson approaches the subject from a systems perspective. How did the subsystems work together (e.g., arms manufacturers and their customers, the various arms of the military/politicians/citizens), the evolution of manufacturing and fighting equipment (the allies did a great job here, Germany not very good, and Japan/Italy terrible) to increase production/lethality, and the prioritizing of activities to achieve aims. The 2011 Christmas books listed “Europe at War” by Norman Davies, which approaches the war from a data perspective.

Through the Language Glass: Why the world looks different in other languages by Guy Deutscher is a science driven discussion (written in a popular style) of the impact of language on the way its speakers interpret their world. While I have read many accounts of the Sapir–Whorf hypothesis, this book was the first to tell me that 70 years earlier, both William Gladstone (yes, that UK prime minister and Homeric scholar) and Lazarus Geiger had proposed theories of color perception based on the color words commonly used by the speakers of a language.

Christmas books for 2021

This year, my list of Christmas books is very late because there is only one entry (first published in 1950), and I was not sure whether a 2021 Christmas book post was worthwhile.

The book is “Planning in Practice: Essays in Aircraft planning in war-time” by Ely Devons. A very readable, practical discussion, with data, on the issues involved in large scale planning; the discussion is timeless. Check out second-hand book sites for low costs editions.

Why isn’t my list longer?

Part of the reason is me. I have not been motivated to find new topics to explore, via books rather than blog posts. Things are starting to change, and perhaps the list will be longer in 2022.

Another reason is the changing nature of book publishing. There is rarely much money to be made from the sale of non-fiction books, and the desire to write down their thoughts and ideas seems to be the force that drives people to write a book. Sites like substack appear to be doing a good job of diverting those with a desire to write something (perhaps some authors will feel the need to create a book length tomb).

Why does an author need a publisher? The nitty-gritty technical details of putting together a book to self-publish are slowly being simplified by automation, e.g., document formatting and proofreading. It’s a win-win situation to make newly written books freely available, at least if they are any good. The author reaches the largest readership (which helps maximize the impact of their ideas), and readers get a free electronic book. Authors of not very good books want to limit the number of people who find this out for themselves, and so charge money for the electronic copy.

Another reason for the small number of good new, non-introductory, books, is having something new to say. Scientific revolutions, or even minor resets, are rare (i.e., measured in multi-decades). Once several good books are available, and nothing much new has happened, why write a new book on the subject?

The market for introductory books is much larger than that for books covering advanced material. While publishers obviously want to target the largest market, these are not the kind of books I tend to read.

My new kitchen clock

After several decades of keeping up with the time, since November my kitchen clock has only been showing the correct time every 12-hours. Before I got to buy a new one, I was asked what I wanted to Christmas, and there was money to spend 🙂

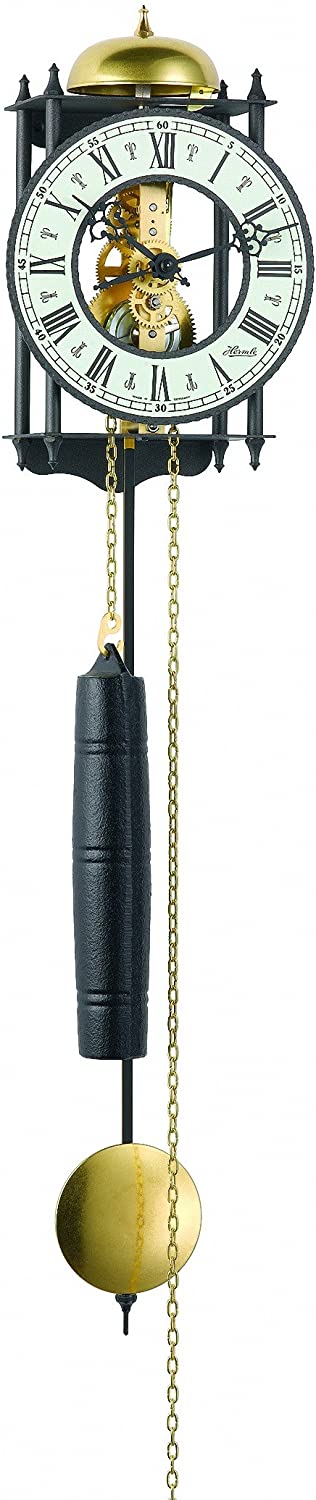

Guess what Santa left for me:

The Hermle Ravensburg is a mechanical clock, driven by the pull of gravity on a cylindrical 1kg of Iron (I assume).

Setup requires installing the energy source (i.e., hang the cylinder on one end of a chain), attach clock to a wall where there is enough distance for the cylinder to slowly ‘fall’, set the time, add energy (i.e., pull the chain so the cylinder is at maximum height), and set the pendulum swinging.

The chain is long enough for eight days of running. However, for the clock to be visible from outside my kitchen I had to place it over a shelf, and running time is limited to 2.5 days before energy has to be added.

The swinging pendulum provides the reference beat for the running of the clock. The cycle time of a pendulum swing is proportional to the square root of the distance of the center of mass from the pivot point. There is an adjustment ring for fine-tuning the swing time (just visible below the circular gold disc of the pendulum).

I used my knowledge of physics to wind the center of mass closer to the pivot to reduce the swing time slightly, overlooking the fact that the thread on the adjustment ring moved a smaller bar running through its center (which moved in the opposite direction when I screwed the ring towards the pivot). Physics+mechanical knowledge got it right on the next iteration.

I have had the clock running 1-second per hour too slow, and 1-second per hour too fast. Current thinking is that the pendulum is being slowed slightly when the cylinder passes on its slow fall (by increased air resistance). Yes dear reader, I have not been resetting the initial conditions before making a calibration run 😐

What else remains to learn, before summer heat has to be adjusted for?

While the clock face and hands may be great for attracting buyers, it has serious usability issues when it comes to telling the time. It is difficult to tell the time without paying more attention than normal; without being a few feet from the clock it is not possible to tell the time by just glancing at it. The see though nature of the face, the black-on-black of the end of the hour/minute hands, and the extension of the minute hand in the opposite direction all combine to really confuse the viewer.

A wire cutter solved the minute hand extension issue, and yellow fluorescent paint solved the black-on-black issue. Ravensburg clock with improved user interface, framed by faded paint of its predecessor below:

There is a discrete ting at the end of every hour. This could be slightly louder, and I plan to add some weight to the bell hammer. Had the bell been attached slightly off center, fine volume adjustment would have been possible.

Christmas books for 2020

A very late post on the interesting books I read this year (only one of which was actually published in 2020). As always the list is short because I did not read many books and/or there is lots of nonsense out there, but this year I have the new excuses of not being able to spend much time on trains and having my own book to finally complete.

I have already reviewed The Weirdest People in the World: How the West Became Psychologically Peculiar and Particularly Prosperous, and it is the must-read of 2020 (after my book, of course :-).

The True Believer by Eric Hoffer. This small, short book provides lots of interesting insights into the motivational factors involved in joining/following/leaving mass movements. Possible connections to software engineering might appear somewhat tenuous, but bits and pieces keep bouncing around my head. There are clearer connections to movements going mainstream this year.

The following two books came from asking what-if questions about the future of software engineering. The books I read suggesting utopian futures did not ring true.

“Money and Motivation: Analysis of Incentives in Industry” by William Whyte provides lots of first-hand experience of worker motivation on the shop floor, along with worker response to management incentives (from the pre-automation 1940s and 1950s). Developer productivity is a common theme in discussions I have around evidence-based software engineering, and this book illustrates the tangled mess that occurs when management and worker aims are not aligned. It is easy to imagine the factory-floor events described playing out in web design companies, with some web-page metric used by management as a proxy for developer productivity.

Labor and Monopoly Capital: The Degradation of Work in the Twentieth Century by Harry Braverman, to quote from Wikipedia, is an “… examination the nature of ‘skill’ and the finding that there was a decline in the use of skilled labor as a result of managerial strategies of workplace control.” It may also have discussed management assault of blue-collar labor under capitalism, but I skipped the obviously political stuff. Management do want to deskill software development, if only because it makes it easier to find staff, with the added benefit that the larger pool of less skilled staff increases management control, e.g., low skilled developers knowing they can be easily replaced.

Christmas books for 2019

The following are the really, and somewhat, interesting books I read this year. I am including the somewhat interesting books to bulk up the numbers; there are probably more books out there that I would find interesting. I just did not read many books this year, what with Amazon recommends being so user unfriendly, and having my nose to the grindstone finishing a book.

First the really interesting.

I have already written about Good Enough: The Tolerance for Mediocrity in Nature and Society by Daniel Milo.

I have also written about The European Guilds: An economic analysis by Sheilagh Ogilvie. Around half-way through I grew weary, and worried readers of my own book might feel the same. Ogilvie nails false beliefs to the floor and machine-guns them. An admirable trait in someone seeking to dispel the false beliefs in current circulation. Some variety in the nailing and machine-gunning would have improved readability.

Moving on to first half really interesting, second half only somewhat.

“In search of stupidity: Over 20 years of high-tech marketing disasters” by Merrill R. Chapman, second edition. This edition is from 2006, and a third edition is promised, like now. The first half is full of great stories about the successes and failures of computer companies in the 1980s and 1990s, by somebody who was intimately involved with them in a sales and marketing capacity. The author does not appear to be so intimately involved, starting around 2000, and the material flags. Worth buying for the first half.

Now the somewhat interesting.

“Can medicine be cured? The corruption of a profession” by Seamus O’Mahony. All those nonsense theories and practices you see going on in software engineering, it’s also happening in medicine. Medicine had a golden age, when progress was made on finding cures for the major diseases, and now it’s mostly smoke and mirrors as people try to maintain the illusion of progress.

“Who we are and how we got here” by David Reich (a genetics professor who is a big name in the field), is the story of the various migrations and interbreeding of ‘human-like’ and human peoples over the last 50,000 years (with some references going as far back as 300,000 years). The author tries to tell two stories, the story of human migrations and the story of the discoveries made by his and other people’s labs. The mixture of stories did not work for me; the story of human migrations/interbreeding was very interesting, but I was not at all interested in when and who discovered what. The last few chapters went off at a tangent, trying to have a politically correct discussion about identity and race issues. The politically correct class are going to hate this book’s findings.

“The Digital Party: Political organization and online democracy” by Paolo Gerbaudo. The internet has enabled some populist political parties to attract hundreds of thousands of members. Are these parties living up to their promises to be truly democratic and representative of members wishes? No, and Gerbaudo does a good job of explaining why (people can easily join up online, and then find more interesting things to do than read about political issues; only a few hard code members get out from behind the screen and become activists).

Suggestions for books that you think I might find interesting welcome.

Christmas books for 2018

The following are the really interesting books I read this year (only one of which was actually published in 2018, everything has to work its way through several piles). The list is short because I did not read many books and/or there is lots of nonsense out there.

The English and their history by Robert Tombs. A hefty paperback, at nearly 1,000 pages, it has been the book I read on train journeys, for most of this year. Full of insights, along with dull sections, a narrative that explains lots of goings-on in a straight-forward manner. I still have a few hundred pages left to go.

The mind is flat by Nick Chater. We experience the world through a few low bandwidth serial links and the brain stitches things together to make it appear that our cognitive hardware/software is a lot more sophisticated. Chater’s background is in cognitive psychology (these days he’s an academic more connected with the business world) and describes the experimental evidence to back up his “mind is flat” model. I found that some of the analogues dragged on too long.

In the readable social learning and evolution category there is: Darwin’s unfinished symphony by Leland and The secret of our success by Henrich. Flipping through them now, I cannot decide which is best. Read the reviews and pick one.

Group problem solving by Laughin. Eye opening. A slim volume, packed with data and analysis.

I have already written about Experimental Psychology by Woodworth.

The Digital Flood: The Diffusion of Information Technology Across the U.S., Europe, and Asia by Cortada. Something of a specialist topic, but if you are into the diffusion of technology, this is surely the definitive book on the diffusion of software systems (covers mostly hardware).

Christmas books for 2017

Some suggestions for books this Christmas. As always, the timing of books I suggest is based on when they reach the top of my books-to-read pile, not when they were published.

“Life ascending: The ten great inventions of evolution” by Nick Lane. The latest thinking (as of 2010) on the major events in the evolution of life. Full of technical detail, very readable, and full of surprises (at least for me).

“How buildings learn” by Stewart Brand. Yes, I’m very late on this one. So building are just like software, people want to change them in ways not planned by their builders, they get put to all kinds of unexpected uses, some of them cannot keep up and get thrown away and rebuilt, while others age gracefully.

“Dead Man Working” by Cederström and Fleming is short and to the point (having an impact on me earlier in the year), while “No-Collar: The humane workplace and its hidden costs” by Andrew Ross is longer (first half is general, second a specific instance involving one company). Both have a coherent view work in the knowledge economy.

If you are into technical books on the knowledge economy, have a look at “Capitalism without capital” by Haskel and Westlake (the second half meanders off, covering alleged social consequences), and “Antitrust law in the new economy” by Mark R. Patterson (existing antitrust thinking is having a very hard time grappling with knowledge-based companies).

If you are into linguistics, then “Constraints on numerical expressions” by Chris Cummins (his PhD thesis is free) provides insight into implicit assumptions contained within numerical expressions (of the human conversation kind). A must read for anybody interested in automated fact checking.

Recent Comments