Archive

The C++ committee has taken off its ball and chain

A step change in the approach to updates and additions to the C++ Standard occurred at the recent WG21 meeting, or rather a change that has been kind of going on for a few meetings has been documented and discussed. Two bullet points at the start of “C++ Stability, Velocity, and Deployment Plans [R2]”, grab reader’s attention:

● Is C++ a language of exciting new features?

● Is C++ a language known for great stability over a long period?

followed by the proposal (which was agreed at the meeting): “The Committee should be willing to consider the design / quality of proposals even if they may cause a change in behavior or failure to compile for existing code.”

We have had 30 years of C++/C compatibility (ok, there have been some nibbling around the edges over the last 15 years). A remarkable achievement, thanks to Bjarne Stroustrup over 30+ years and 64 full-week standards’ meetings (also, Tom Plum and Bill Plauger were engaged in shuttle diplomacy between WG14 and WG21).

The C/C++ superset/different issue has a long history.

In the late 1980s SC22 (the top-level ISO committee for programming languages) asked WG14 (the C committee) whether a standard should be created for C++, and if so did WG14 want to create it. WG14 considered the matter at its April 1989 meeting, and replied that in its view a standard for C++ was worth considering, but that the C committee were not the people to do it.

In 1990, SC22 started a study group to look into whether a working group for C++ should be created and in the U.S. X3 (the ANSI committee responsible for Information processing systems) set up X3J16. The showdown meeting of what would become WG21, was held in London, March 1992 (the only ISO C++ meeting I have attended).

The X3J16 people were in London for the ISO meeting, which was heated at times. The two public positions were: 1) work should start on a standard for C++, 2) C++ was not yet mature enough for work to start on a standard.

The, not so public, reason given for wanting to start work on a standard was to stop, or at least slow down, changes to the language. New releases, rumored and/or actual, of Cfront were frequent (in a pre-Internet time sense). Writing large applications in a version of C++ that was replaced with something sightly different six months later had developers in large companies pulling their hair out.

You might have thought that compiler vendors would be happy for the language to be changing on a regular basis; changes provide an incentive for users to pay for compiler upgrades. In practice the changes were so significant that major rework was needed by somebody who knew what they were doing, i.e., expensive people had to be paid; vendors were more used to putting effort into marketing minor updates. It was claimed that implementing a C++ compiler required seven times the effort of implementing a C compiler. I have no idea how true this claim might have been (it might have been one vendor’s approximate experience). In the 1980s everybody and his dog had their own C compiler and most of those who had tried, had run into a brick wall trying to implement a C++ compiler.

The stop/slow down changing C++ vs. let C++ “fulfill its destiny” (a rallying call from the AT&T rep, which the whole room cheered) finally got voted on; the study group became a WG (I cannot tell you the numbers; the meeting minutes are not online and I cannot find a paper copy {we had those until the mid/late-90s}).

The creation of WG21 did not have the intended effect (slowing down changes to the language); Stroustrup joined the committee and C++ evolution continued apace. However, from the developers’ perspective language change did slow down; Cfront changes stopped because its code was collapsing under its own evolutionary weight and usable C++ compilers became available from other vendors (in the early days, Zortech C++ was a major boost to the spread of usage).

The last WG21 meeting had 140 people on the attendance list; they were not all bored consultants looking for a creative outlet (i.e., exciting new features), but I’m sure many would be happy to drop the ball-and-chain (otherwise known as C compatibility).

I think there will be lots of proposals that will break C compatibility in one way or another and some will make it into a published standard. The claim will be that the changes will make life easier for future C++ developers (a claim made by proponents of every language, for which there is zero empirical evidence). The only way of finding out whether a change has long term benefit is to wait a long time and see what happens.

The interesting question is how C++ compiler vendors will react to breaking changes in the language standard. There are not many production compilers out there these days, i.e., not a lot of competition. What incentive does a compiler vendor have to release a version of their compiler that will likely break existing code? Compiler validation, against a standard, is now history.

If WG21 make too many breaking changes, they could find C++ vendors ignoring them and developers asking whether the ISO C++ standards’ committee is past its sell by date.

A survey of opinions on the behavior of various C constructs

The Cerberus project, researching C semantics, has written up the results of their survey of ‘expert’ C users (short version and long detailed version). I took part in the original survey and at times found myself having to second guess what the questioner was asking; the people involved were/are still learning how C works. Anyway, many of the replies provide interesting insights into current developer interpretation of the behavior of various C constructs (while many of the respondents were compiler writers, it looks like some of them were not C compiler writers).

Some of those working on the Cerberus project are proposing changes to the C standard based on issues they encountered while writing a formal specification for parts of C and are bolstering their argument, in part, using the results of their survey. In many ways the content of the C Standard was derived from a survey of those attending WG14 meetings (or rather x3j11 meetings back in the day).

I think there is zero probability that any of these proposed changes will make it into a revised C standard; none of the reasons are technical and include:

- If it isn’t broken, don’t fix it. Lots of people have successfully implemented compilers based on the text of the standard, which is the purpose of the document. Where is the cost/benefit of changing the wording to enable a formal specification using one particular mathematical notation?

- WG14 receives lots of requests for changes to the C Standard and has an implicit filtering process. If the person making the request thinks the change is important, they will:

- put the effort into wording the proposal in the stylized form used for language change proposals (i.e., not intersperse changes in a long document discussing another matter),

- be regular attendees of WG14 meetings, working with committee members on committee business and helping to navigate their proposals through the process (turning up to part of a meeting will see your proposal disappear as soon as you leave the building; the next WG14 meeting is in London during April).

It could be argued that having to attend many meetings around the world favors those working for large companies. In practice only a few large companies see any benefit in sending an employee to a standard’s meeting for a week to work on something that may be of long term benefit them (sometimes a hardware company who wants to make sure that C can be compiled efficiently to their processors).

The standard’s creation process is about stability (don’t break existing code; many years ago a company voted against a revision to the Cobol standard because they had lost the source code to one of their products and could not check whether the proposed updates would break this code) and broad appeal (not narrow interests).

Update: Herb Sutter’s C++ trip report gives an interesting overview of the process adopted by WG21.

Single-quote as a digit separator soon to be in C++

At the C++ Standard’s meeting in Chicago last week agreement was finally reached on what somebody in the language standards world referred to as one of the longest bike-shed controversies; the C++14 draft that goes out for voting real-soon-now will include support for single-quotation-mark as a digit separator. Assuming the draft makes it through ISO voting you could soon be writing (Compiler support assumed) 32'767 and 0.000'001 and even 1'2'3'4'5'6'7'8'9 if you so fancied, in your conforming C++ programs.

Why use single-quote? Wouldn’t underscore have been better? This issue has been on the go since 2007 and if you feel really strongly about it the next bike-shed C++ Standard’s meeting is in Issaquah, WA at the start of next year.

Changing the lexical grammar of a language is fraught with danger; will there be a change in the behavior of existing code? If the answer is Yes, then the next question is how many people will be affected and how badly? Let’s investigate; here are the lexical details of the proposed change:

pp-number: digit . digit pp-number digit pp-number ' digit pp-number ' nondigit pp-number identifier-nondigit pp-number e sign pp-number E sign pp-number . |

Ideally the change of behavior should cause the compiler to generate a diagnostic, when code containing it is encountered, so the developer gets to see the problem and do something about it. The following conforming C++ code will upset a C++14 compiler (when I write C++ I mean the C++ Standard as it exists in 2013, i.e., what was called C++11 before it was ratified):

#define M(x) #x // stringize the macro argument char *p=M(1'2,3'4); |

At the moment the call to the macro M contains one argument, the sequence of three tokens {1}, {'2,3'} and {4} (the usual convention is to bracket the characters making up one token with matching curly braces).

In C++14 the call to M will contain the two arguments {1'2} and {3,4}. conforming compiler is required to complain when the number of arguments to a macro invocation don’t match the definition…. Unless the macro is defined to accept a variable number of arguments:

#define M(x, ...) __VA_ARGS__ int x[2] = { M(1'2,3'4) }; // C++11: int x[2] = {}; // C++14: int x[2] = { 3'4 }; |

This is the worst kind of change in behavior, known as a silent change, the existing code compiles without complaint but has different behavior.

How much existing code contains either of these constructs? I suspect very very little human written code, maybe even none. This is the sort of stuff that is more likely to be produced by automatic code generators. But how much more likely? I have no idea.

How much benefit does the new feature provide? It certainly looks useful, but coming up with a number for the benefit is hard. I guess it has the potential to shave a fraction of a second off of the attention a developer has to pay when reading code, after they have invested in learning about the construct (which is lots of seconds). Multiplied over many developers and not that many instances (the majority of numeric literals contain a single digit), we could be talking a man year or two per year of worldwide development effort?

All of the examples I have seen require the ‘assistance’ of macros, here is another (courtesy of Jeff Snyer):

#define M(x) A ## x #define A0xb int operator "" _de(char); int x = M(0xb'c'_de); |

Are there any examples of a silent change that don’t involve the preprocessor?

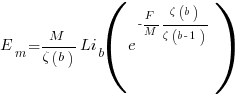

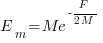

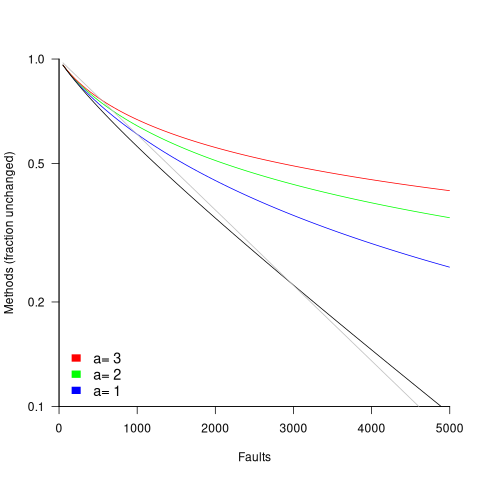

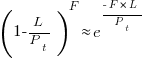

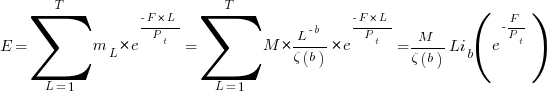

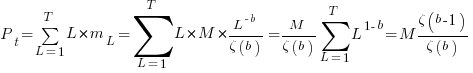

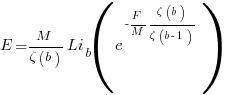

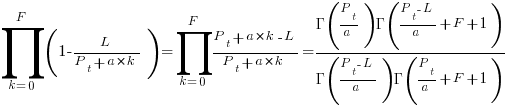

in lines of code, of the method. The evidence shows that the

in lines of code, of the method. The evidence shows that the  ).

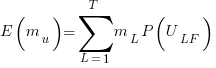

). reported faults have been fixed in a program containing

reported faults have been fixed in a program containing  methods/functions, what is the expected number of methods that have not been modified by the fixing process?

methods/functions, what is the expected number of methods that have not been modified by the fixing process?

is the

is the  is the

is the  for Java.

for Java. (

(

, where

, where  is the number of previously detected coding mistakes in the method.

is the number of previously detected coding mistakes in the method.

is the average value of

is the average value of  over all

over all  , then

, then  for a power law with exponent 2.35).

for a power law with exponent 2.35).

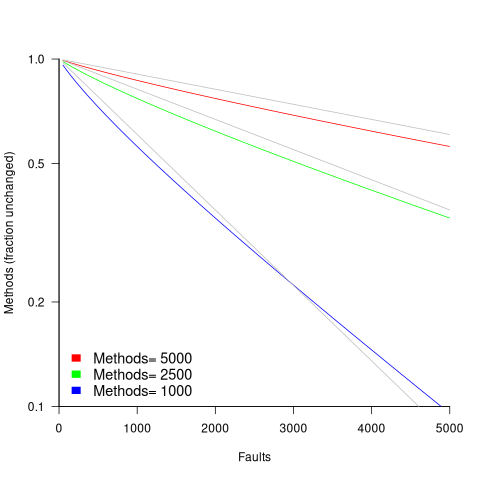

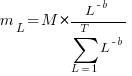

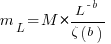

, is:

, is: , where

, where  is the length of the longest method,

is the length of the longest method,  is the number of methods of length

is the number of methods of length  is the probability that a method of length

is the probability that a method of length  , where

, where  , then the sum can be approximated by the

, then the sum can be approximated by the

, where

, where  is the total lines of code in the program, and the probability of this method not being modified after

is the total lines of code in the program, and the probability of this method not being modified after

the average value of

the average value of  is the

is the  we get:

we get:

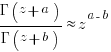

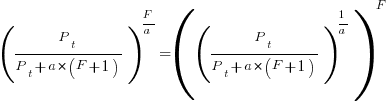

is the preferential attachment version of the expression

is the preferential attachment version of the expression  appearing in the simple model derivation. Using this preferential attachment expression in the analysis of the simple model, we get:

appearing in the simple model derivation. Using this preferential attachment expression in the analysis of the simple model, we get:

Recent Comments