Archive

Hardware/Software cost ratio folklore

What percentage of data processing budgets is spent on software, compared to hardware?

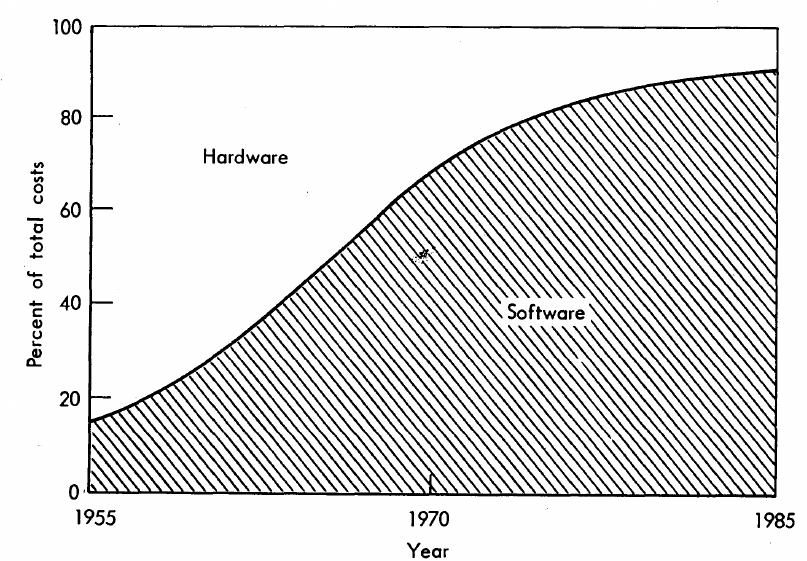

The information in the plot below quickly became, and remains, the accepted wisdom, after it was published in May 1973 (page 49).

Is this another tale from software folklore? What does the evidence have to say?

What data did Barry Boehm use as the basis for this 1973 article?

Volume IV of the report Information processing/data automation implications of Air-Force command and control requirements in the 1980s (CCIP-85)(U), Technology trends: Software, contains this exact same plot, and Boehm is a co-author of volume XI of this CCIP-85 report (May 1972).

Neither the article or report explicitly calls out specific instances of hardware/software costs. However, Boehm’s RAND report Software and Its Impact A Quantitative Assessment (Dec 1972) gives three examples: the US Air Force estimated they will spend three times as much on software compared to hardware (in early 1970s), a military C&C system ($50-100 million hardware, $722 million software), and recent NASA expenditure ($100 million hardware, $200 million software; page 41).

The 10% hardware/90% software division by 1985 is a prediction made by Boehm (probably with others involved in the CCIP-85 work).

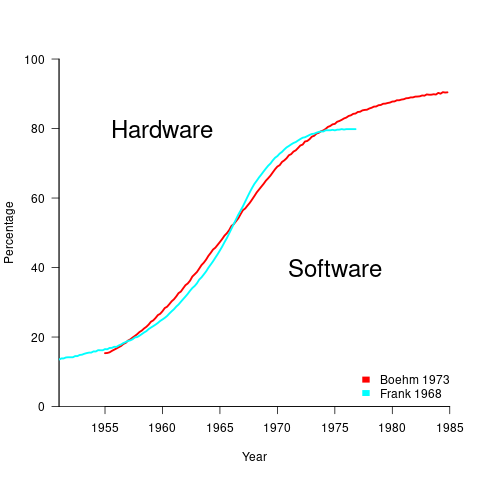

What is the source for the 1955 percentage breakdown? The 1968 article Software for Terminal-oriented systems (page 30) by Werner L. Frank may provide the answer (it also makes a prediction about future hardware/software cost ratios). The plot below shows both the Frank and Boehm data based on values extracted using WebPlotDigitizer (code+data):

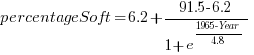

What about the shape of Boehm’s curve? A logistic equation is a possible choice, given just the start/end points, and fitting a regression model finds that  is an almost perfect fit (code+data).

is an almost perfect fit (code+data).

How well does the 1972 prediction agree with 1985 reality?

At the start of the 1980s, two people wrote articles addressing this question: The myth of the hardware/software cost ratio by Harvey Cragon in 1982, and The history of Myth No.1 (page 252) by Werner L. Frank in 1983.

Cragon’s article cites several major ecosystems where recent hardware/software percentage ratios are comparable to Boehm’s ratios from the early 1970s, i.e., no change. Cragon suggests that Boehm’s data applies to a particular kind of project, where a non-recurring cost was invested to develop a new software system either for a single deployment or with more hardware to be purchased at a later date.

When the cost of software is spread over multiple installations, the percentage cost of software can dramatically shrink. It’s the one-of-a-kind developments where software can consume most of the budget.

Boehm’s published a response to Cragon’s article, which answered some misinterpretations of the points raised by Cragdon, and finished by claiming that the two of them agreed on the major points.

The development of software systems was still very new in the 1960s, and ambitious projects were started without knowing much about the realities of software development. It’s no surprise that software costs were so great a percentage of the total budget. Most of Boehm’s articles/reports are taken up with proposed cost reduction ideas, with the hardware/software ratio used to illustrate how ‘unbalanced’ the costs have become, an example of the still widely held belief that hardware costs should consume most of a budget.

Frank’s article references Cragon’s article, and then goes on to spend most of its words citing other articles that are quoting Boehm’s prediction as if it were reality; the second page is devoted 15 plots taken from these articles. Frank feels that he and Boehm share the responsibility for creating what he calls “Myth No. 1” (in a 1978 article, he lists The Ten Great Software Myths).

What happened at the start of 1980, when it was obvious that the software/hardware ratio predicted was not going to happen by 1985? Yes, obviously, move the date of the apocalypse forward; in this case to 1990.

Cragon’s article plots software/hardware budget data from an uncited Air Force report from 1980(?). I managed to find a 1984 report listing more data. Fitting a regression model finds that both hardware and software growth is deemed to be quadratic, with software predicted to consume 84% of DoD budget by 1990 (code+data).

Did software consume 84% of the DoD computer/hardware budget in 1990? Pointers to any subsequent predictions welcome.

Three books discuss three small data sets

During the early years of a new field, experimental data relating to important topics can be very thin on the ground. Ever since the first computer was built, there has been a lot of data on the characteristics of the hardware. Data on the characteristics of software, and the people who write it, has been (and often continues to be) very thin on the ground.

Books are sometimes written by the researchers who produce the first data associated with an important topic, even if the data set is tiny; being first often generates enough interest for a book length treatment to be considered worthwhile.

As a field progresses lots more data becomes available, and the discussion in subsequent books can be based on findings from more experiments and lots more data

Software engineering is a field where a few ‘first’ data books have been published, followed by silence, or rather lots of arm waving and little new data. The fall of Rome has been followed by a 40-year dark-age, from which we are slowly emerging.

Three of these ‘first’ data books are:

- “Man-Computer Problem Solving” by Harold Sackman, published in 1970, relating to experimental data from 1966. The experiments investigated the impact of two different approaches to developing software, on programmer performance (i.e., batch processing vs. on-line development; code+data). The first paper on this work appeared in an obscure journal in 1967, and was followed in the same issue by a critique pointing out the wide margin of uncertainty in the measurements (the critique agreed that running such experiments was a laudable goal).

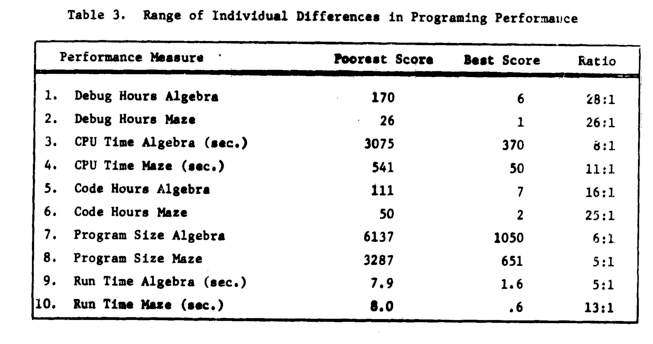

Failing to deal with experimental uncertainty is nothing compared to what happened next. A 1968 paper in a widely read journal, the Communications of the ACM, contained the following table (extracted from a higher quality scan of a 1966 report by the same authors, and available online).

The tale of 1:28 ratio of programmer performance, found in an experiment by Grant/Sackman, took off (the technical detail that a lot of the difference was down to the techniques subjects’ used, and not the people themselves, got lost). The Grant/Sackman ‘finding’ used to be frequently quoted in some circles (or at least it did when I moved in them, I don’t know often it is cited today). In 1999, Lutz Prechelt wrote an expose on the sorry tale.

Sackman’s book is very readable, and contains lots of details and data not present in the papers, including survey data and a discussion of the intrinsic uncertainties associated with the experiment; it also contains the table above.

- “Software Engineering Economics” by Barry W. Boehm, published in 1981. I wrote about the poor analysis of the data contained in this book a few years ago.

The rest of this book contains plenty of interesting material, and even sounds modern (because books moving the topic forward have not been written).

- “Program Evolution: Process of Software Change” edited by M. M. Lehman and L. A. Belady, published in 1985, relating to experimental data from 1977 and before. Lehman and Belady managed to obtain data relating to 19 releases of an IBM software product (yes, 19, not nineteen-thousand); the data was primarily the date and number of modules contained in each release, plus less specific information about number of statements. This data was sliced and diced every which way, and the book contains many papers with the same data appearing in the same plot with different captions (had the book not been a collection of papers it would have been considerably shorter).

With a lot less data than Isaac Newton had available to formulate his three laws, Lehman and Belady came up with five, six, seven… “laws of software evolution” (which themselves evolved with the publication of successive papers).

The availability of Open source repositories means there is now a lot more software system evolution data available. Lehman’s laws have not stood the test of more data, although people still cite them every now and again.

Recent Comments