Archive

Christmas books for 2024

My rate of book reading has picked up significantly this year. The following are the really interesting books I read, as is usually the case, most were not published in this year.

I have enjoyed Grayson Perry’s TV programs on the art world, so I bought his book “Playing to the Gallery: Helping Contemporary Art in its Struggle to Be Understood“. It’s a fun, mischievous look at the art world by somebody working as a traditional artist, in the sense of creating work that they believe means/says something, rather than works that are only considered art because they are displayed in an art gallery.

“The Computer from Pascal to von Neumann” by H. H. Goldstine. This history of computing from the mid-1600s (the time of Blaise Pascal) to the mid-1900s (von Neumann died in 1957) told by a mathematician who was first involved in calculating artillery firing tables during World War II, and then worked with early computers and von Neumann. This book is full of insights that only a technical person could provide and is a joy to read.

I saw a poster advertising a guided tour of the trees in my local park, organized by Trees for Cities. It was a very interesting lunchtime; I had not appreciated how many different trees were growing there, including three different kinds of Oak tree. Trees for Cities run events all over the UK, and abroad. Of course, I had to buy some books to improve my tree recognition skills. I found “Collins tree guide” by O. Johnson and D. More to be the most useful and full of information. Various organizations have created maps of trees in cities around the world. The London Tree Map shows the location and species information for over 880,000 of trees growing on streets (not parks), New York also has a map. For a general analysis of patterns of tree growth, see “How to Read a Tree” by T. Gooley.

“Medieval Horizons: Why the Middle Ages Matter” by I. Mortimer. This book takes the reader through the social, cultural and economic changes that happened in England during the Middle Ages, which the author specifies as the period 1000 to 1600. I knew that many people were surfs, but did not know that slaves accounted for around 10% of the population, dropping to zero percent during this period. Changes, at least for the well-off, included moving from living in longhouses to living in what we would call a house, art works moved from two-dimensional representations to life-like images (e.g., renaissance quality), printing enables an explosion of books, non-poor people travelled more, ate better, and individualism started to take-off.

Statistical Consequences of Fat Tails: Real World Preasymptotics, Epistemology, and Applications by N. N. Taleb is a mathematically dense book (while the pdf is in color, I was disappointed that the printed version is black/white; this is the one I read while travelling). This book tells you a lot more than you need to know about the consequences of fat tail distributions. Why might you be interested in the problems of fat tails? Taleb starts by showing how little noise it takes for the comforting assumptions implied by the Normal/Gaussian distribution to fly out the window. The primary comforting assumptions are that the mean and variance of a small sample are representative of the larger population. A world of fat tail distributions is one where the unexpected is to be expected, where a single event can wipe out an organization or industry (banks are said to have lost more in the 2008 financial crisis than they had made in the previous many decades). This book is hard going, and I kept at it to get a feel for the answers to some of the objections to the bad news conveyed. There are a couple of places where I should have been more circumspect in my Evidence-based software engineering book.

I have previously reviewed General Relativity: The Theoretical Minimum by Susskind and Cabannes.

“Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II” by John W. Dower describes in harrowing detail the dire circumstances of the population of Japan immediately after World War II and what they had to endure to survive.

For more detailed book reviews, see: Mr. and Mrs. Psmith’s Bookshelf with some excellent and insightful long book reviews, and the annual Astral Codex Ten book review contest usually has a few excellent reviews/books.

For those of you who think that civilization is about to collapse, or at least like talking about the possibility, a reading list. At the practical level, I think sword fighting and archery skills are more likely to be useful in the longer term.

Creating and evolving a programming language: funding

The funding for artists and designers/implementors of programming languages shares some similarities.

Rich patrons used to sponsor a few talented painters/sculptors/etc, although many artists had no sponsors and worked for little or no money. Designers of programming languages sometimes have a rich patron, in the form of a company looking to gain some commercial advantage, with most language designers have a day job and work on their side project that might have a connection to their job (e.g., researchers).

Why would a rich patron sponsor the creation of an art work/language?

Possible reasons include: Enhancing the patron’s reputation within the culture in which they move (attracting followers, social or commercial), and influencing people’s thinking (to have views that are more in line with those of the patron).

The during 2009-2012 it suddenly became fashionable for major tech companies to have their own home-grown corporate language: Go, Rust, Dart and Typescript are some of the languages that achieved a notable level of brand recognition. Microsoft, with its long-standing focus on developers, was ahead of the game, with the introduction of F# in 2005 (and other languages in earlier and later years). The introduction of Swift and Hack in 2014 were driven by solid commercial motives (i.e., control of developers and reduced maintenance costs respectively); Google’s adoption of Kotlin, introduced by a minor patron in 2011, was driven by their losing of the Oracle Java lawsuit.

Less rich patrons also sponsor languages, with the idiosyncratic Ivor Tiefenbrun even sponsoring the creation of a bespoke cpu to speed up the execution of programs written in the company language.

The benefits of having a rich sponsor is the opportunity it provides to continue working on what has been created, evolving it into something new.

Self sponsored individuals and groups also create new languages, with recent more well known examples including Clojure and Julia.

What opportunities are available for initially self sponsored individuals to support themselves, while they continue to work on what has been created?

The growth of the middle class, and its interest in art, provided a means for artists to fund their work by attracting smaller sums from a wider audience.

In the last 10-15 years, some language creators have fostered a community driven approach to evolving and promoting their work. As well as being directly involved in working on the language and its infrastructure, members of a community may also contribute or help raise funds. There has been a tiny trickle of developers leaving their day job to work full time on ‘their’ language.

The term Hedonism driven development is a good description of this kind of community development.

People have been creating new languages since computers were invented, and I don’t expect this desire to create new languages to stop anytime soon. How long might a language community be expected to last?

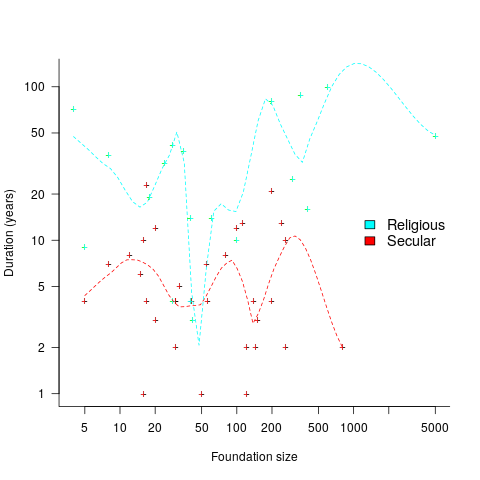

Having lots of commercially important code implemented in a language creates an incentive for that language’s continual existence, e.g., companies paying for support. When little or co commercial important code is available to create an external incentive, a language community will continue to be active for as long as its members invest in it. The plot below shows the lifetime of 32 secular and 19 religious 19th century American utopian communities, based on their size at foundation; lines are fitted loess regression (code+data):

How many self-sustaining language communities are there, and how many might the world’s population support?

My tracking of new language communities is a side effect of the blogs I follow and the few community sites a visit regularly; so a tiny subset of the possibilities. I know of a handful of ‘new’ language communities; with ‘new’ as in not having a Wikipedia page (yet).

One list contains, up until 2005, 7,446 languages. I would not be surprised if this was off by almost an order of magnitude. Wikipedia has a very idiosyncratic and brief timeline of programming languages, and a very incomplete list of programming languages.

I await a future social science PhD thesis for a more thorough analysis of current numbers.

Learning R as a language

Books written to teach a general purpose programming language are usually organized according to the features of the language and examples often show how a particular language feature is interpreted by a compiler. Books about domain specific languages are usually organized in a way that makes sense in the corresponding application domain and examples usually illustrate how a particular domain problem can be solved using the language.

I have spent a lot of time using R over the last year and by dint of reading lots of R code and various introductions to the language I have managed to piece together a model of the language. I rarely have any trouble learning a general purpose language from its reference manual, but users of domain specific languages are rarely interested in language details and so these reference manuals are usually only intended to be read by people who know the language well (another learning problem is that domain specific languages often contain quirky features rarely seen in other languages; in the case of R I was not lucky enough to know enough other languages to cover all its quirky features).

I managed to one introduction to R written from the perspective of the programming language (and not the application domain): the original The Art of R Programming by Norman Matloff has been expanded and is now available as a book.

Summary. If you know another language and want to quickly learn about the languages features of R I recommend this book. I have not taught raw beginners for over 30 years and have no idea if this book would be of any use to them.

This book does not attempt to teach you to think ‘R’, it is not about the art of R programming. The value of this book is as a single source for a broad coverage of lots of language features explained using lots of examples. Yes, more time could have been spent on the organization and fixing inconsistencies in the layout; these are not show stoppers.

Some people might tell you to buy “Software for Data Analysis” by John Chambers. Don’t; if you are a fan of Finnegans Wake and are nostalgic for the mainframe world of the 1970s you might like to give it a go. (I think Bertrand Meyer’s “Object-oriented Software Construction” is still the best book about the design of a language).

Meanderings. What books are good examples of “The Art of …” writing for domain specific languages? Two that spring to mind are: “Algorithms in Snobol 4” by James Gimpel (still spotted from time to time on second hand book sites) and more recently “SQL For Smarties: Advanced SQL Programming” by Joe Celko.

Yes, I know that R is not really a domain specific language but a language that is primarily used in one domain. Frink is an example of a language containing a major behavior feature that is specific to its intended application domain. I cannot think of any major language feature of R that is specific to statistics.

Recent Comments