Hardware variability may be greater than algorithmic improvement

I’m giving a talk at COW 39 this week and it is more user friendly to include links in this summary than link to a pdf of the slides (which actually looks horrible).

Microelectronic fabrication has now reached the point where it etches and deposits handfuls of atoms (around 20 or so). One consequence of working with such a small number of atoms is that variations in the fabrication process (e.g., plus or minus a few atoms here and there) can have a significant impact on component characteristics, e.g., a transistor consumes more/less power or can be switched faster/slower. It might be argued that things will average out over the few hundred+ million components inside a device and that all devices will be essentially the same; measurements show that in practice there is a lot of variation across the devices.

Short version: Some properties of supposedly identical microelectronic devices now vary by around 10% and this variability is likely to get larger in the future.

Nearly all published papers involving computer system power measurement are based on measuring a single system. Many of the claimed algorithmic improvements are less than 10%, i.e., less than the expected variation in power consumption across supposedly identical devices/systems. These days any empirical paper involving power consumption has to include measurements from many devices/systems if any credibility is to be given to the findings.

The following measurement data has been found while researching for a book (code and data used for talk); a beta version of the pdf will be available for download real soon now.

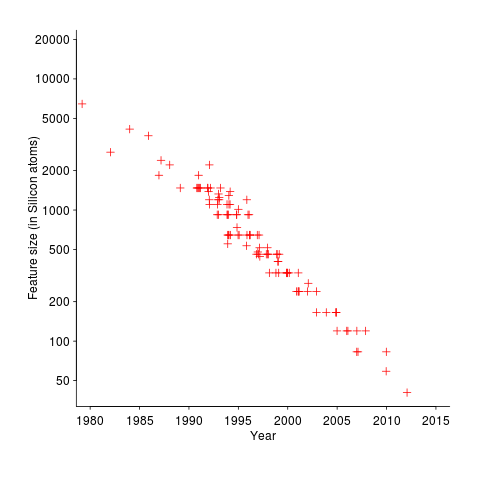

The following plot shows feature size, in Silicon atoms, of released microprocessors. Data from Danowitz et al.

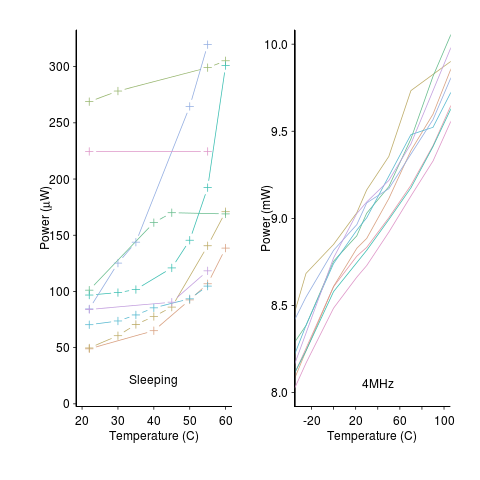

A study by Wanner, Apte, Balani, Gupta and Srivastava measured the power consumed by 10 separate Amtel SAM3U microcontrollers at various temperatures (embedded processors get used in a wide range of environments). The following plot shows how power consumption varied between processors at different temperatures when idling and executing. The relationship between the power characteristics of different processors changes with temperature; a large amount when idling and a little bit when executing.

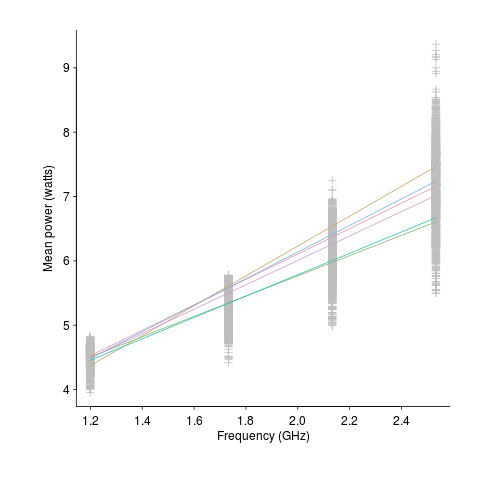

A study by Balaji, McCullough, Gupta and Agarwal measured the power consumption of six different Intel Core i5-540M processors, running at various frequencies, executing the SPEC2000 benchmark. The lines in the following plot were fitted to the data (grey crosses) using linear regression. The relationship between the power characteristics of different processors changes with clock frequency.

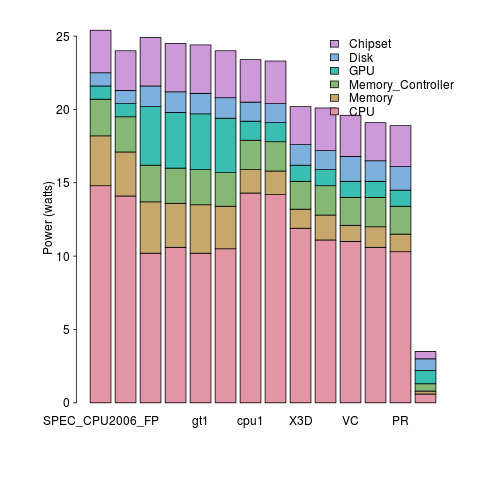

A study by Bircher measured power consumption of various system components, of an Intel server containing four Pentium 4 Xeons, when executing the SPEC CPU2006 benchmark. The power distribution for mobile devices would show the screen being the largest user of power, but I don’t have that data).

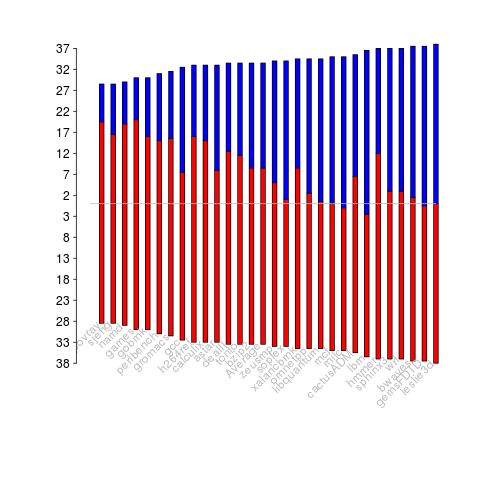

A study by Bircher measured memory (blue) and cpu (red) power consumption, in watts, executing the SPEC CPU2006 benchmarks. No point optimizig cpu power if over half the total power is consumed by memory.

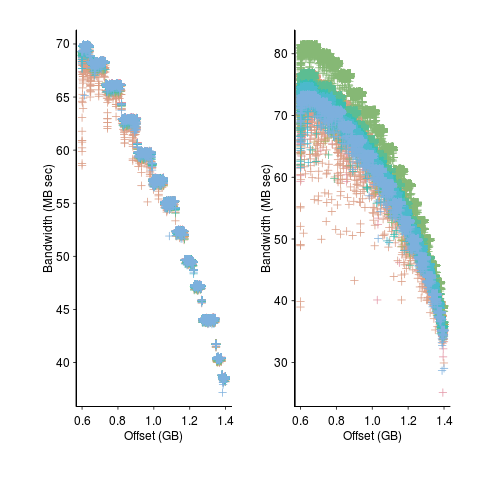

A study by Krevat, Tucek and Ganger measured the performance of then modern disk drives originally sold in 2002 (left) and 2006 (right). Different colors showing through on the right indicates that some discs have different performance characteristics than the others (faster performance -> less time -> less power, i.e., I don’t have power data for disk differences)

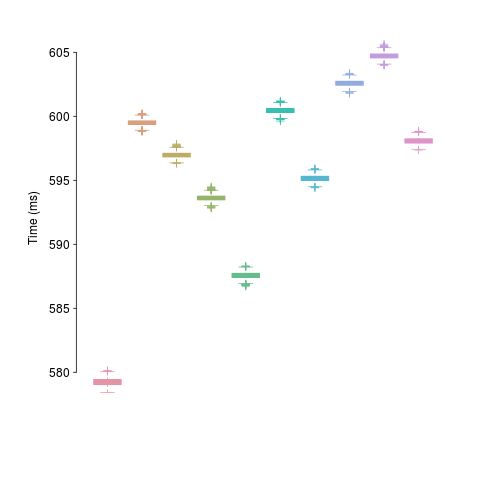

A study by Kalibera et al executed a benchmark 2,048 times followed by system reboot, repeated 10 times. Performance is consistent within a particular reboot, but not across them.

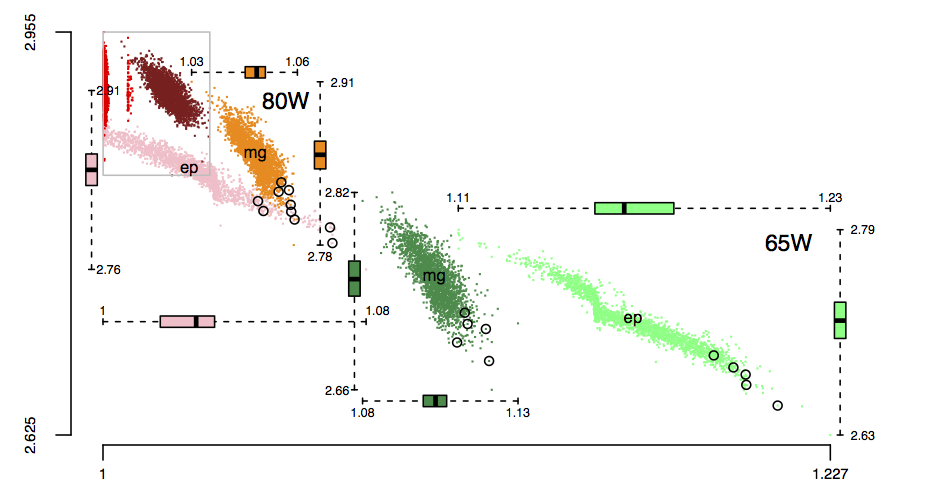

The following plot is in the slide deck and is included here as a teaser (i.e., more later). It shows data for 2,386 processors (x-axis is slowdown, y-axis clock frequency, top right legends max power), which thanks to Barry is now publicly available (or at least will be once some web details are sorted out).

Long tail licensing

Team ‘Long Tail Licensing’ (Richard, Pavel, Gary and yours truly) took part in the Fintech startupbootcamp hackathon at the weekend.

As the team name suggests the plan was to implement a system of payment and licensing for products in the long tail, i.e., a large number of low value products. Paypal is good for long tail payment but does not provide a way for third parties to verify that a transaction has occurred (in fact Paypal does its best to keep transactions secret from everybody except those directly involved).

Our example use case was licensing of individual Github repositories. Most of today’s 3.4 million developers with accounts on Github would rather add more features to their code than try to sell it; the 16.7 million repositories definitely qualifies as a long tail of low value products (i.e., under £100). Yes, Paypal could be (and is) used as a method of obtaining payment, but there is no friction-free method for handling licensing (e.g., providing proof of licensing to third parties).

Long Tail Licensing’s implementation used cryptocurrency for both payment and proof of licensing (by storing license information in the blockchain). For the hackathon we set up out own private Bitcoin blockchain to act as a test rig, supply fast mining and provide near instantaneous response.

To use Long Term Licensing a developer creates the file .cryptolicense in the top level directory of their repo; this file contain information on the amount to pay, cryptocurrency account details and text of licensing terms. A link in the README.md file points at our server, which validates the .cryptocurrency file and sets up a payment transaction from the licensee’s Bitcoin wallet; the licensee confirms the transaction and the payment is made.

The developer’s chosen license information is included in the transactions blockchain, providing the paperwork that third-parties can view to verify what has been licensed. This licensing information could be in plain text or use public key encryption to restrict who can read it (e.g., eBay could publish a public key that third parties could encrypt information so that only eBay’s compliance department could read it).

The implementation code includes links to private servers and other stuff that it should not be be; hackathon code is rarely written with security in mind. So those involved would rather it not be pushed to Github (perhaps it will get tidied up and made suitable for public consumption at a later date).

We did not win any of the prizes :-(. Well done to Manoj (a frequent hackathon collaborator) and his team for winning the $100k of Google cloud time prize.

Do languages evolve to minimise portability?

Governments promote standards because following them helps their citizens save money. The UK and US have contrasting positions, with the UK focusing on savings achieved through the repeated use of standardized items and the US focusing on the repeated use of skills people acquired through using a standardized item.

What benefit, if any, do product vendors receive from adhering to a standard? A few vendors may be in a position to use economies of scale to gain market share (by driving out of business less well funded competitors), other vendors follow a specified standard as a means of winning a contract with large customers, and the rest don’t care.

In the program language world, for 20 odd years, there were just the Cobol and Fortran standards. These started out idealistically driven because hardware vendors had to convince potential customers that it was commercially viable for them to write software for the products they were selling (i.e., the early computers). Once business started to take off, the computer industry’s compete/cooperate dynamic, mixed with large egos wanting their own way and the sales driven mandate to keep existing customers happy (i.e., don’t break existing code) took over. There was lots of infighting and progress was slow, but at least there were lots of people who thought it important enough to be involved.

In the mid-1980s there was a seismic shift in approach to language standards with Pascal and C becoming ISO standards, the first created by a group of mainly academics and the second by a group containing many small company consultants/vendors. The age of ‘activist’ language ISO standard creation had begun; which is not to say that anything changed in the Cobol and Fortran standards’ world. For a look back at this decade see: Computer Standards & Interfaces, volume 16, numbers 5 & 6, Sep 1994.

If you were to put somebody who knew nothing about computer languages in a room with the standard’s committees for Modula-2 and C++, I don’t think they would be able to tell them apart. Inside the bubble, it’s not possible to distinguish the language that died before its standard was published and the language that continues to grow like Topsy.

Activists want to get things done and will select the route of minimal bureaucratic resistance. These days this means that new language standards are often created locally and fed into the ISO process higher once they are done.

Open source compilers have solved many of the source portability problems caused by language dialects, that standards were intended to solve, by dramatically shrinking the market of the compilers that supported those dialects.

Where has the user been in all this? Well, where-ever they are, they are rarely seen at language standard meetings.

These days, portability problems are caused by the multitude of languages, not by the multitude of dialects of a language.

Top secret free information

I may or may not have been at a top secret hackathon at the weekend.

If you read the above text please leave your contact details in the comments so I can arrange to have somebody come round and shoot you.

In other news, I saw last week that the European Delegated Act requires that the European Space Agency to provide “Free and open access to Sentinel satellite data…” A requirement that is not incompatible with the wording above.

Live coding, where should I send my invoice for performance royalties?

Live coding (i.e., performance art + coding) is the shiny new thing in trendy circles (which is why it was a while before I heard about it). I’m sure readers have had the experience of having to code around issues on customer sites while everyone looked on, this is certainly a performance and there is an art to making it look like minor issues, rather than major problems, are being sorted out.

Isn’t musical improvisation live coding? Something that people like J. S. Bach were doing hundreds of years ago.

I don’t think that the TOPLAP (Transdimensional Organisation for the Permanence of Live Algorithm Programming) website is aimed at people like me, but I did enjoy the absurdity of its manifesto.

Who originated the term live coding? Perhaps it was a salesman trying to turn the poor user interface on the product he was peddling into desirable feature, i.e., having to write code to get the instrument to play a tune is a benefit.

Live performers are always looking for a new angle to attract the public. Perhaps they have noticed the various efforts to get kids coding and have adapted the message to their own ends. No, that cannot be true, academics are making arduous journeys to German country houses to discuss this emerging new technology Don’t worry if you missed out, you can attend the First Live Coding International Conference in July!

I’m sure live coding will get a few students programming who would otherwise have gone off and done something else. But then so would a few rainy weekends.

I suspect that most developers would prefer to do fewer live coding sessions.

My 2cents on the design of the contract language in Ethereum

My previous post on Ethereum contracts got me thinking about how Ethereum should be going about creating a language and virtual machine for the contracts aspect of their cryptocurrency.

I would base the contract development gui on Scratch. Contract development will involve business people and having been extensively field tested on children Scratch stands some chance of being usable for business types.

For the language itself I would find a language already being used for contract related programming and simply adopt it.

At the moment the internal specification of contracts is visible for all to see. I expect a lot of people will be unwilling to share contract information with anybody outside of those they are dealing with. The Ethereum Virtual Machine needs to include opcodes that perform Homomorphic encryption, i.e., operations on encrypted values producing a result that is the encrypted version of the result from performing the same operation on the unencrypted values. Homomorphic encryption operations would allow writers of contracts that keep sensitive numeric values secret, they get to decide who gets a copy of thee dencryption keys needed to see the plain-text result.

The only way I see of overcoming the denial-of-service attack outlined in my previous post is to require that the miner who receives payment for executing a contract prove that they did the work of executing the contract by including program values existing at various randomly chosen points of contract execution.

Ethereum contracts, is the design viable?

I went to a workshop run by Ethereum today, to learn about cryptocurrency/virtual currency from a developer’s point of view. Ethereum can be thought of as Bitcoin+contracts; they are also doing various things to address some of the design problems experienced by Bitcoin. This article is about the contract component of Ethereum, which is being promoted as its unique selling point.

The Ethereum people talk so much about contacts that I thought once currency (known as ether, a finney is a thousandth of an ether, with other names going down to  ) had been mined it was not considered legal tender until it was associated with the execution of a contract. In fact people will be free to mine as many ethers as they like without having any involvement with the contract side of things.

) had been mined it was not considered legal tender until it was associated with the execution of a contract. In fact people will be free to mine as many ethers as they like without having any involvement with the contract side of things.

Ethereum expect the computational cost of mining to be significantly greater than the cost of executing contracts.

A contract is a self-contained piece of code created by a client and executed by a miner (the client pays the miner for this service). The result of executing the contract is added to the data associated with a block of mined currency (only one contract per block).

How confident can the client, and interested third parties, be that the miner paid to execute the contract is telling the truth and didn’t make up the data included in the mined currency block?

The solution adopted by Ethereum is to require all miners involved in the execution of contracts to execute all contracts that have been associated with mined currency, so that the result posted by the miner who got paid to execute each contract can be validated (51% agreement is required).

For this design to work, the cost of executing contracts to verify the data produced by other miners has to be small relative to paid income received from executing contracts.

If somebody is in the ether mining business, executing contracts has the potential to provide additional income for a small increase in effort, i.e., the currency has been mined why not get paid to execute contracts, adding the resulting data to blocks that have been mined?

Ethereum has specified the relative cost of operations executed by the Ethereum Virtual Machine. The Client specifies a value used to multiply these costs to produce an actual cost per operation that are willing to pay.

Requiring the community of contract executors to execute all contracts creates a possible vulnerability that can be exploited.

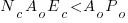

To profit from executing contracts the following condition must hold:

where:  is the ratio of unpaid to paid contracts,

is the ratio of unpaid to paid contracts,  is the average number of operations performed per contract,

is the average number of operations performed per contract,  is the average execution cost per operation and

is the average execution cost per operation and  is the average amount clients pay per operation.

is the average amount clients pay per operation.

This simplifies to:

What would be a reasonable estimate for  , the ratio of unpaid to paid contracts? Would 1,000 miners offering contract execution services be a reasonable number? If we assume that contracts are evenly distributed among everybody involved in contract execution, then there are disincentives of scale; every new market entrant reduces income and increases costs for existing members.

, the ratio of unpaid to paid contracts? Would 1,000 miners offering contract execution services be a reasonable number? If we assume that contracts are evenly distributed among everybody involved in contract execution, then there are disincentives of scale; every new market entrant reduces income and increases costs for existing members.

What if businessman Bob wants to corner the contract market and decides to drive up the cost of executing contracts for all miners except himself? To do this he enlists the help of accomplice Alice as a client offering contracts at extremely poorly paid rates, which Bob is happy to accept and be paid for appearing to execute them (Alice has told him the result of executing the contracts); these contracts are expensive to execute, but Bob and Alice know number theory and don’t need a computer to figure out the results.

So Bob, Alice and all their university chums flood the Ethereum currency world with expensive to compute contracts. What conditions need to hold for them to continue profiting from executing contracts?

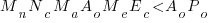

Lets assume that expensive contracts dominate, then the profitability condition becomes:

where:  is the increase in the number of contracts,

is the increase in the number of contracts,  the increase in the average number of operations performed per contract and

the increase in the average number of operations performed per contract and  the increase in average execution cost per operation.

the increase in average execution cost per operation.

This simplifies to:

What values do we assign to the three multipliers:  ? Lets say

? Lets say  , which tells us that the price paid has to increase by a factor of 150 for those involved in the market to maintain the same profit level.

, which tells us that the price paid has to increase by a factor of 150 for those involved in the market to maintain the same profit level.

Given that Ethereum are making such a big fuss about contracts I had expected the language being used to express contracts to be tailored to that task. No such luck. Serpent is superficially Python-like, with the latest release moving in a Perl-ish direction, not in themselves a problem. The problem is that the languages is not business oriented, let alone contract oriented, and is really just a collection of features bolted together (the self absorbed use case for the new float type: “… elliptic curve signature pubkey recovery code…”, says it all). Another Ethereum language Mutan is claimed to be C-like; well, it does use curly brackets rather than indentation to denote scope.

If Ethereum does fly, then there is an opportunity for somebody to add-on a domain specific language for contracts, one that has the kind of built in checks that anybody involved with contracting will want to use t prevent expensive mistakes being made.

Users of Open source software are either the product or are irrelevant

Users of software often believe that the people who produced it are interested in the views and opinions of their users.

In a commercial environment there are producers who are interested in what users have to say, because of the financial incentive, and some Open source software exists within this framework, e.g., companies selling support services for the code they have Open sourced.

Without a commercial framework why would any producer of Open source be interested in the views and opinions of users? Answers include:

- users are the product: I have met developers who are strongly motivated by the pleasure they get from being at the center of a community, i.e., the community of people using the software that they are actively involved in creating,

- users are irrelevant: other developers are more strongly motivated by the pleasure of building things and in particular building using what are considered to be the right tools and techniques, i.e., the good-enough approach is not considered to be good-enough.

How do these Open source dynamics play out in the evolution of software systems?

It is the business types who are user oriented or rather source of money oriented. They are the people who stop developers from upsetting customers by introducing incompatibilities with previous releases, in fact a lot of the time its the business types pushing developers to concentrate on fixing problems and not wasting time doing more interesting stuff.

Keeping existing customers happy often means that products change slowly and gradually ossify (unless the company involved has a dominant market position that forces users to take what they are given).

A project primarily fueled its developers’ desire for pleasure cannot stand still, it has to change. Users who complain that change has an impact on their immediate need for compatibility get told that today’s pain is necessary for a brighter future tomorrow.

An example of users as the product is gcc. Companies pay people to work on gcc because they want access to the huge amount of software written by ‘the product’ using gcc.

As example of users as irrelevant is llvm. Apple is paying for llvm to happen and what does this have to do with anybody else using it?

The users of Angular.js now know what camp they are in.

As Bob Dylan pointed out: “Just because you like my stuff doesn’t mean I owe you anything.”

Z and Zermelo–Fraenkel

Z is for Z and Zermelo–Fraenkel.

Z, pronounced zed, or Z notation to give it its full name, replaced VDM as the fashionable formal specification language before itself falling out of fashion. Gallina is in fashion today, but you are more likely to have heard of the application software built around it, Coq.

Zermelo–Fraenkel set theory with the axiom of choice is the brand name assembly language of mathematics (there are a number of less well known alternatives). Your author is not aware of any large program written in this assembly language (Principia Mathematica used symbolic logic and over 300 pages to prove that 1+1=2).

While many mathematical theorems can be derived from the axioms contained in Zermelo–Fraenkel, mathematicians consider some to be a lot more interesting than others (just like developers consider some programs to be more interesting than others). There have been various attempts to automate the process of discovering ‘interesting’ theorems, with Eurisko being the most famous and controversial example.

Things to read

Automated Reasoning: Introduction and Applications by Larry Wos, Ross Overbeek, Rusty Lusk, and Jim Boyle. A gentle introduction to automated reasoning based on Otter.

… and it is done.

Readers may have noticed the sparse coverage of languages created between the mid-1990s and 2010. This was the programming language Dark ages, when everybody and his laptop was busy reinventing existing languages at Internet speed; your author willfully tried to ignore new languages during this time. The focus for reinvention has now shifted to web frameworks and interesting new ideas are easier to spot amongst the noise.

Merry Christmas and a happy New Year to you all.

XSLT, yacc and Yorick

X and Y are for XSLT, yacc and Yorick.

XSLT is the tree climbing Kangaroo of the programming language world. Eating your own dog food is good practice for implementors, but users should not be forced to endure it. Anyway, people only use XML, rather than JSON, to increase the size of their files so they can claim to be working with big data.

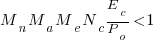

yacc grammars don’t qualify as programming languages because they are not Turing complete (because yacc requires its input to be a deterministic context-free grammar, a subset of context-free grammars, that can be implemented using a deterministic pushdown automaton; restructering a context-free grammar into a deterministic context-free grammar is the part of using yacc that mangles the mind the most). While Bison supports GLR parsing, this only extends its input to all context-free grammars; the same notation is used to specify grammars and this does not support the specification of languages such as:  , where

, where  and

and  denotes

denotes  repeated

repeated  times, which requires a context-free grammar. So the yacc grammar notation is not capable of expressing all computations.

times, which requires a context-free grammar. So the yacc grammar notation is not capable of expressing all computations.

Yorick is designed for processing large amounts of scientific data and is a lot like R, with slightly different syntax. Use of Yorick seems to have died out in the last few years. What happened, did its users discover R? I would certainly recommend a switch to R, but I would also suggest Yorick as a subject of study for the maintainers of R; there are language ideas to be mulled over, e.g., global("blah") to declare blah as being a global variable within the function containing the call.

Things to read

The Theory of Parsing, Translation, and Compiling, Vol. 1, Parsing by Alfred V. Aho and Jeffrey D. Ullman. Warning, reading this book will make your head hurt.

Introduction to Automata Theory, Languages, and Computation by John Hopcroft and Jeffrey D. Ullman. Has a great chapter on Turing machines. If you really want your head to hurt, then get the book above rather than the first edition of this book.

Recent Comments