ALGEC: ALGorithmic language for EConomic problems

I have been reading about ALGEC, the computer language invented in the Soviet Union during the early 1960s, courtesy of a translation of the article Report on the Working Sessions of the Group on Algorithmic Languages for Processing Economic Information (GAIAPEI) by Rand.

The Soviet Union ran a command economy and the job of computers was obviously to process economic information.

The language is based on Algol 60, the default base language for the design of most establishment driven programming languages.

Since the Soviets were the only country to build a computer that used ternary logic, I was hoping that the language would include support for this ‘feature’. No such luck.

Two features caught by attention:

- Keywords can be written in a form that denotes their gender and number. For instance,

Booleancan be written:логическое(neuter),логический(masculine),логическая(feminine) andлогические(plural). - The keyword for the go to token is

to. There is obviously something about the use of Russian that makes it obvious that the word go should not be part of this keyword.

Do readers know of any other computer language which have been influence by features of the designers native human language (apart, obviously from all the English derived computer languages)?

Happy 10th birthday to CREST

Most university departments run regularly seminars and in July 2001 I attended a half day workshop run by Mark Harman at Brunel University. Over the years the workshop has changed names, locations and grown into a two day event with a worldwide reputation.

When Mark became professor of software engineering at University College London, the workshops became known as the CREST Open Workshops and next month the 47th workshop will celebrate 10 years of the CREST centre. Workshops vary from being mostly theory oriented to mostly practice oriented; the contents is always leading edge stuff. For many years the talks have been filmed and the back catalog contains plenty of interesting material.

If you are interested in the latest software engineering related issues, at a rather technical level, then keep an eye out for upcoming CREST workshops. The theory/practice orientation of a workshop is usually easy to guess from the style of papers written by the speakers. There are other software engineering groups dotted around the world; I have no experience of their seminars/workshops, but I’m sure they will make you feel welcome.

So, here’s to another 10 years of interesting workshops.

Some CREST related blog posts:

Human vs automatically generated source code: an arms race?

Machine learning in SE research is a bigger train wreck than I imagined

Hardware variability may be greater than algorithmic improvement

Workshop on App Store Analysis

Fortran & Cobol in the USAF over the years 1955-1986

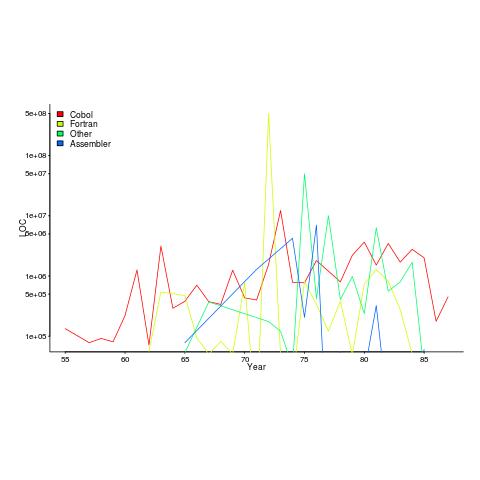

I recently discovered a new dataset from Rome’s golden age, going back to 1955. Who knew that in 1955 the US Air Force took delivery of 133,075 lines of Cobol? The plot below shows lines of code against year, broken down by major languages used.

I got the data from the Master’s thesis of Captain NeSmith II (there is probably more software engineering data to be found in US Air Force officers’ Master’s thesis than all published academic papers before 2005). Captain NeSmith got his data from the Information Systems Designator (ISD) database maintained by the Standard Information Systems Center (SISC); the data does not include classified project and embedded systems. This database contained more data than appeared in the thesis, but I cannot find it anywhere.

Given the spiky nature of the data I’m guessing that LOC and development costs are counted in the year a project is delivered. Maintenance costs are through to financial year 1984.

The big question that jumps out of the data is “What project delivered 0.5 billion lines of Fortran in 1972?”

The LOC for Assemble suspiciously does not occur before 1965.

In the 1980s people were always talking about the billion+ lines of Cobol in use by the US Government. Over the 31 year span of this USAF data, 46 million lines of Cobol were delivered at a cost of $0.5 billion. Did another 50 arms of the government produce similar amounts of Cobol? Is the USAF under/over representative of Cobol?

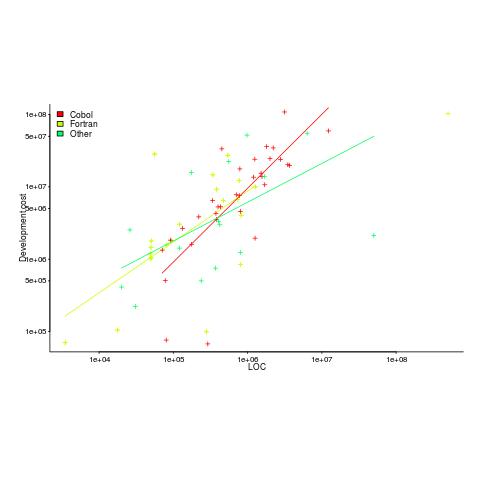

The plot below shows yearly LOC against development cost, plus fitted regression lines.

Using development cost as a proxy for effort, the coefficients of the fitted lines were close to those I fitted to Boehm’s embedded data (i.e., the exponents were lower than those listed by Boehm); Fortran 0.7, Cobol 1 and Other 0.5 (the huge Fortran outlier was excluded).

Adding Year to the regression model shows than Fortran development cost decreased by around 8% per year. Cobol may have been around 1% per year, depending on which model is chosen.

The maintenance costs can be plotted, but there is just too much uncertainty about them to say anything sensible (was inflation taken into account, how heavily used were the programs {more usage find more faults and demand for more features}, etc.).

NeSmith’s thesis contains a lot more data. The reproduction quality is not great, so the numbers have to be typed in. If you find any bugs in my data+code, please let me know and if you type in any of the other tables I would love a copy.

Is the ISO C++ standard’s committee past its sell by date?

The purpose of having a standard is economic. The classic (British) example is screw threads, having a standard set of screw threads means that products from different manufacturers are interchangeable and competition drives down prices; the US puts more emphasis on standards being an enabler of people interchangeability, i.e., train people once and they can use the acquired skills in multiple companies.

In the early days of computing we had umpteen compilers for Cobol, Fortran and then Pascal and then C and then C++. There were a lot of benefit to be had getting the vendors signed up to support a single standard for their language (of course they still added bells and whistles to ‘enhance’ their offerings). Language standard’s meeting were full of vendors, with a few end users (mostly from large corporations and government).

Fast forward to today and the ranks of compiler vendors has thinned significantly. Microfocus dominates Cobol, Fortran is dominated by a few number cruncher oriented companies, Pascal die hards cling on in surprising places, C vendors are till in double figures (down by an order of magnitude from its heyday) and C++ vendors will soon be accurately countable by Trolls (1, 2, 3, many).

What purpose does an ISO language standard serve in a world with only a few compilers? These days the standard is actually set by the huge volume of existing code that has to be handled by any vendor hoping to be adopted by developers.

The ISO C++ committee has become the playground of bored consultants looking for a creative outlet that work is not providing. Is there any red blooded developer who would not love spending a week, two or three times a year, holed up in a hotel with 100+ similarly minded people pouring over newly invented language features?

Does the world need all these new features in C++? Fortunately for the committee there are training companies who like nothing better than being able to offer ‘latest features of C++’ courses to all those developers who have been on previous ‘latest features of C++’ courses. Then there is the media, who just love writing about new stuff, there is even an ‘official’ C++ Standard news outlet.

In the good old days compiler vendors loved updates to the language standard because it gave them an opportunity to sell upgrades to customers; things are a bit different in the open source compiler market. What is the incentive of an open source compiler vendor to support features added by an ISO committee? In the past there has been a community expectation that it will happen, but is the ground swell of opinion enough to warrant spending resources on supporting new languages? Perhaps the GCC and LLVM folk will get together and mutually agree not to waste resources being the first mover.

Would developers at large notice if the C++ committee didn’t do anything for the next 10 years?

The Javascript ECMAscript standard also has a membership that includes many end users. In this case I suspect companies are sending people to make sure that new languages features don’t impact large code bases and existing investment in ways of doing things.

Update: I’m not saying that C++ language and libraries should stop evolving, but questioning the need to have an ISO Standard’s committee in a world of Open Source and a small number of compilers (that is likely to only become fewer).

AEC hackathon: what do the coloured squiggles mean?

I was at the AEC hackathon last weekend. There were a whole host of sponsors, but there was talk of project sponsorship for teams trying to solve a problem involving London’s Crossrail project. So most of those present were tightly huddled around tables, intently whispering to each other about their crossrail hack (plenty of slide-ware during the presentations).

I arrived at hacker time (a bit later than all the keen folk who had been waiting outside for the doors to open from eight’ish) and missed out on forming a team. Talking to Nik and Geoff, from the Future Cities Catapult (one of the sponsors), I learned about the 15 sensor packages that had been distributed around the building we were in (Intel Photon+Smartcitizen sensor kits, connected via the local wifi).

These sensors had been registered with the Smart Citizen platform and various environmental measurements, around each sensor, was being recorded at 1 minute resolution. The sensors had been set up a few days earlier, so only recent data was available.

The Smart Citizen dashboard provided last recorded values and a historical plot for each sensor on its own (example here). The Future Cities guys wanted something a bit more powerful, and team Coloured Squiggles set to work (one full-time member, plus anyone who dawdled within conversation range).

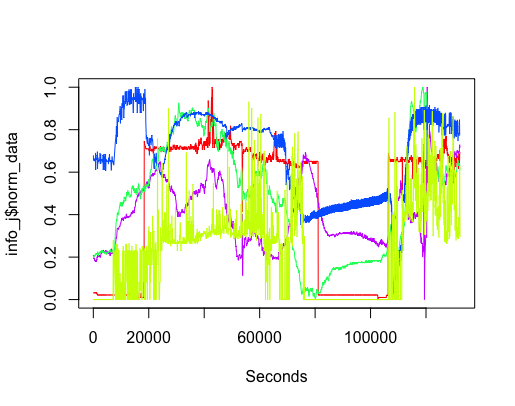

It did not take long, using R, to extract and plot the data from various sensors (code). The plot below shows just over a day’s worth of data from the sensor installed in the basement (where the hackathon took place). The red line is ambient light (which is all internal because we are underground), yellowish is sound level (the low level activity before the lights come on is air-conditioning switching on ready for Friday morning, there is no such activity for Saturday morning), blue is carbon monoxide (more about that later), green is nitrogen dioxide and purple is humidity. Values have been normalised.

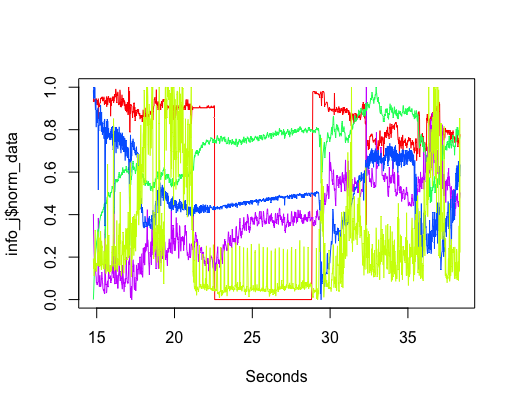

The interesting part of the project was interpreting the squiggly lines; what was making them go up and down. Nik was a great source of ideas and being involved with setting the sensors up knew about the kind of environment they were in, e.g., basement, by the window (a source of light) and on top of the coffee machine (which was on a fridge, whose cooling motor on/off cycling we eventually decided was causing the periodic nighttime spikes in the sound level seen in yellow below {ignore the x-axis values}).

The variation in the level of Carbon-Monoxide was discussed a lot. IoT sensors are very low cost, and so it is easy to question the quality of their output. However, all sensors showed this same pattern of behavior, although some contained more noise than others (compare the thickness of the blue lines in the above plots). One idea was that CO is heavier than air and sinks to the floor at night and gets stirred up in the morning, but Wikipedia says it is not heavier than air. Another idea was that the air-conditioning allows fresh outside into the building in the morning, which gets gradually gets filtered.

The lessons learned was that a sensor’s immediate environment can cause all sorts of unexpected variation in its output. The only way to figure out what is going on is by walking around talking to the people who occupy the same space as the sensor.

The final version provided a browser based interface, allowing individual devices and multiple sensor output to be selected (everything is on github).

When will Microsoft stop bothering to sell compilers?

The amount of money Microsoft make from selling compilers is peanuts compared to the profits from their Office and OS products (they may even lose money), and this will never change.

In the 80s, when the IBM PC was first introduced and began to take over the computing world, the Microsoft C compiler was not the market leader and not the favorite among developers who had a choice (large companies preferred to buy from large companies and so Microsoft C did well in the corporate market).

The developer market back then was not large and companies selling compilers soon found themselves selling into a saturated market, and many disappeared.

C++ came along and compiler companies jumped on this bandwagon, giving them a new product to sell for a few years.

As an OS vendor, Microsoft needed its own compiler to appear credible to developers. The libraries (the one part of the compiler suite that everybody liked) came along for free, courtesy of being an OS vendor. The IDE, Visual Studio, has grown on developers over time and has gotten a lot better. Visual C++ became the dominant Windows compiler because it was the last man standing.

Like all compilers, Visual C++ supports its own way of doing things in various parts of the language. Use of compiler language foibles are the mechanism by which application developers build porting cost barriers, to other compilers, into their code. Any large application built using Visual C++ will need a lot of effort to port to another compiler, a benefit for Microsoft.

The porting cost generated by compiler differences is a two-way street. Porting applications from another compiler to Visual C++ could be just as expensive as porting from Visual C++.

Microsoft can remove the cost of porting to Windows by supporting llvm within Visual Studio (I don’t ever see them supporting gcc for licensing reasons), plus command line support so that existing make files work and at the end of last year they sort of did just that (they bolted the llvm C/C++ front end onto the code generators for Visual C++; they obviously did not want to cause embarrassment by making it easy for developers to compare the performance of generated code ;-).

There is a large potential downside for Microsoft supporting llvm, it provides an in-your-face opportunity for current Visual C++ users to try another compiler (I suspect a goodly number have never touched any other C+ compiler). The problem with existing Visual C++ user accessing other compilers is not about code quality (Microsoft compilers have never been known for generating the fastest code), it is about making it easy for developers to learn how to make their code portable to other compilers.

Why would a company want to support a version of its product that compiles with Visual C++ abd a version that compiles with llvm? In the short term expediency, but in the long term it makes sense to use a single compiler.

Microsoft has ported it’s Office products to non-Windows platforms. Was Visual C++ involved? Using Visual C++ would have meant extending it to support the language extensions that occur in the headers files present on other platforms. There are advantages to using the compiler used to build the OS and I suspect this is what the Office team did (I don’t have any inside knowledge).

Is the only long term customer of Visual C++ the Windows development group? I wonder how hard it would be to tweak Windows+llvm so that one could build the other?

The writing is on the wall for Visual C++; how long does it have? Five years, 10?

I would not be surprised if there are a few very large customers, with many millions of lines of code they do not want to touch, who would put up the money to keep the development group on life support. Visual studio could be around 50 years from now, kept alive by the need to compile huge dinosaurs that are not quite important enough or cause enough grief to warrant rewriting. Perhaps it will end up being the oldest commercial compiler still in production use.

Least Recently Used: The experiment that made its reputation

Today we all know that least recently used is the best page replacement algorithm for virtual memory systems (actually paging is complicated in today’s intertwined computing world).

Virtual memory was invented in 1959 and researchers spent the 1960s trying to figure out the best page replacement algorithm.

Programs were believed to spend most of their time in loops and this formed the basis for the rationale for why FIFO, First In First Out, was the best page replacement algorithm (widely used at the time).

Least recently used, LRU, was on people’s radar as a possible technique and was mathematically analysed, along with various other techniques. The optimal technique was known and given the name OPT; a beautifully simple technique with one implementation drawback, it required knowledge of future memory usage behavior (needless to say some researchers set to work trying to predict future memory usage, so this algorithm could be used).

An experiment by Tsao, Comeau and Margolin, published in 1972, showed that LRU outperformed FIFO and random replacement. The rest, as they say, is history; in this case almost completely forgotten history.

The paper “A multifactor paging experiment: I. The experiment and conclusions” was published as one of a collection of papers in “Statistical Computer Performance Evaluation” edited by Freiberger. A second paper by two of the authors in the same book outlines the statistical methodology. Appearing in a book means this paper can be very hard to track down. I recently bought a copy of the book on Amazon for one penny (the postage was £2.80).

The paper contains a copy of the experimental results and below are the page swap numbers:

loadseq group group group freq freq freq alpha alpha alpha Pages 24 20 16 24 20 16 24 20 16 LRU S 32 48 538 52 244 998 59 536 1348 LRU M 53 81 1901 112 776 3621 121 1879 4639 LRU L 142 197 5689 262 2625 10012 980 5698 12880 FIFO S 49 67 789 79 390 1373 85 814 1693 FIFO M 100 134 3152 164 1255 4912 206 3394 5838 FIFO L 233 350 9100 458 3688 13531 1633 10022 17117 RAND S 62 100 1103 111 480 1782 111 839 2190 RAND M 96 245 3807 237 1502 6007 286 3092 7654 RAND L 265 2012 12429 517 4870 18602 1728 8834 23134 |

Three Fortran programs were used, Small (55 statements), Medium (215 statements) and Large (595 statements). These programs were loaded by group (sequences of frequently called subroutines grouped together), freq (subrotines causing the most page swaps were grouped together), alpha (subroutines were grouped alphabetically).

The system was configured with either 24, 20 or 16 pages of 4,096 bytes; it had a total of 256K of memory (a lot of memory back then). The experiment consumed 60 cpu hours.

Looking at the table, it is easy to see that LRU has the best performance. In places random replacement beats FIFO. A regression model (code and data) puts numbers on the performance advantage.

The paper says that the only interaction was between memory size (i.e., number of pages) and how the programs were loaded. I found pairwise interaction between all variables, but then I am using a technique that was being invented as this paper was being published (see code for details).

Number of page swaps was one of three techniques used for measuring performed. The other two were activity count (average number of pages in main memory referenced at least once between page swaps) and inactivity count (average time, measured in page swaps, of a page in secondary storage after it had been swapped out). See data for details.

I vividly remember dropping in on a randomly chosen lecture in computer science in the mid-70s (I studied physics and electronics), the subject was page selection algorithms and there were probably only a dozen people in the room (physics and electronics sometimes had close to 100). The lecturer regaled those present with how surprising it was that LRU was the best and somebody had actually done an experiment showing this. Having a physics/electronics background, the experimental approach to settling questions was second nature to me.

GitHub, the logical next purchase for Microsoft after LinkedIn

Active directory sits at the center of the Microsoft corporate product line, providing identity related services. All the Microsoft services use it to figure out what users can and cannot do. Ensuring it was possible for third parties to implement Active Directory was on the must-do task list during the compliance phase of the EU/Microsoft competition case.

With the LinkedIn purchase Microsoft has acquired the base from which to implement Active Directory for companies operating in the cloud; the identity service used by companies to monitor employees looks like it will continue to be owned and operated by Microsoft.

People have been known to be inventive when writing their cvs and LinkedIn profiles are unlikely to be any different. How do Microsoft introduce some quality control to the claims appearing in profiles?

One way of verifying the claims made by software developers, about what projects they have worked on and how much they contributed, is to look at the code they have written. If Microsoft owned GitHub they would be in a position to do just that, starting with its 14 million users.

What you know a developers employment history and the code they wrote, all sorts of services can be offered. Companies are rightly concerned about the intellectual property of the software they produce and use. Microsoft would be in a position to provide a code IP checking service, the code produced by company employees could be compared against the code they wrote at previous companies to produce a similarity value. This checking option can be sold to all companies in a developer’s work history; companies want to know that when an employee leaves they don’t take anything with them.

Technical details. You would be correct to point out that quantity of code written is not a sensible predictor of developer productivity. Not a problem when selling to management, there are enough academic studies associating quantity with productivity to make management believe otherwise.

Microsoft don’t actually need to see the source code to perform a lot of similarity checks. Many clone detection tools work by comparing hashes of small sequences of particular code features; comparing constructs.

Finding the gold nugget papers in software engineering research

Academic research projects are like startups in that most fail to make any return on their investment (e.g., the tax payer does not get any money back) and a few pay for themselves and all the failures. Irrespective of whether a project succeeds or fails, those involved will publish papers on the work, give talks at conferences and workshops and general try to convince anyone who will listen that the project was a great success.

Number or papers published plays an important role in evaluating the quality of a university department and the performance on an individual researcher. As you can imagine, this publish or perish culture leads to huge amounts of clueless nonsense ending up in print. Don’t be fooled by the ‘peer reviewed’ label, most of this gets done by the least experienced people (e.g., postgrad students) as a means of gaining social recognition in their specific research community, i.e., those doing the reviewing don’t always know much.

The huge number of papers describing failed projects and/or containing clueless nonsense is a major obstacle for anyone wanting to locate useful new knowledge.

While writing my C book I refined the following approach to finding high quality papers and created filtering rules for the subjects it covered. The rules below are being applied to papers relating to my Empirical Software Engineering book. I don’t claim any usefulness for these rules outside of academic software engineering research.

I use a scatter gun approach to obtain a basic collection of papers followed by ruthless filtering.

The scatter gun approach might start with one or two papers; following links on Google Scholar or even just Google search results filtered on “filetype:pdf”, in the past I have used CiteSeer which Google now does a better job of indexing, and Semantic Scholar is now starting to be quite good.

After 30 minutes or so I have 50 pdfs (I download maybe 4,000 a year). Now I need to quickly filter the nonsense to end up with maybe 10 that I will spend 5 minutes each reading, leaving maybe 2 or 3 for detailed reading (often not the original ones I started with).

When dealing with this kind of volume you have to be ruthless.

Spend just 10 seconds on the first pass. If a paper has some merits, let it remain for the next pass. Scan the paper looking for major indicators of clueless nonsense; these are not hard to spot, don’t linger, hit the delete (if data is involved, it is worth quickly checking the footnotes for a url to a dataset, which may be new and worth collecting):

- it relies on machine learning,

- it relies on information theory,

- it relies on Halstead’s metric,

- it investigates software quality. This is a marketing term used to give a patina of relevance to the worthless metric that is likely used in the research. Be on the lookout for other high relevance terms being used to provide a positive association with a worthless metric, e.g., developer productivity defined as volume of code written

- it involves fault prediction. Academic folk psychology includes a belief that some project files contain more faults than other files, because more faults are reported in some files than others (or even that entire projects are more reliable because fewer faults have been reported). This is a case of the drunk searching under a streetlight for lost keys because that is where the ground can be seen. Faults are found by executing code, more execution means more faults. I only know of two papers that are exceptions to this rule (one of them is discussed here),

- the primary claim in the conclusion is to have done something novel. Research requires doing new stuff, novel is a key attribute that is rather pointless for its own sake. Typing code using your nose would be novel, but would you want to spend more than 10 seconds reading a paper on the subject (and this example is at the more sensible end of the spectrum of novel research I have read about).

The first pass removes around 70-80% of the papers, at least for me.

For the second pass I will spend a minute or so doing a slightly slower scan. This often cuts the papers remaining in half.

By now, I have been collecting and filtering for over 90 minutes; time to do something else, perhaps not returning for many hours.

The third pass involves trying to read the paper. The question is: Am I having trouble reading this paper because the author has managed to compress a lot of useful information into a publication page limit, or is the paper so bad I cannot see the wood for the dead trees?

Answering this question takes practice and some knowledge of the subject area. You will speed up with practice and learning about the subject.

Some things that might be thought worth paying attention to, but should be ignored:

- don’t bother looking at the names of the authors or which university they work at (who wrote the paper almost always provides no clues to its quality; there are very few exceptions to this and you will learn who they are over time),

- ignore the journal or conference that published the paper (gold nuggets appear everywhere and high impact venues only restrict the clueless nonsense to the current trendy topics and papers citing the ‘right’ people),

- ignore year of publication, quality is ageless (and sometimes fades from view because research fashions change).

If you have your own tips for finding the gold nuggets in software engineering, please let me know.

Predicting the next value in an integer sequence

There was a Kaggle meetup group hackathon on Saturday. Integer sequence learning is a recently posted Kaggle challenge; build a model to predict the next value in an integer sequence, with example data coming from the On-Line Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences. How could I not want to try my hand at this challenge, and I signed up for the hackathon hoping to find like-minded folk.

My only previous encounter with mining the OEIS was a paper that attempted to combine two or more existing sequences to match one existing sequence and to contribute a few sequences I had found.

The event was well attended, and I found a fellow enthusiast in Lampros.

We kicked around a few ideas and while I jumped in and started investigating the characteristics of the data, Lampros started searching for solutions that others had found to the next value in an integer sequence problem (a much more sensible approach, but probably not as much fun as jumping in feet first; this was his first hackathon, so he has not picked up any bad habits yet ;-).

This is one of those few problems when over-fitting is required for things to work.

I concentrated on characterizing the 113,845 sequences in the training set and the following is a summary (code and data):

- 74,465 sequences contained a maximum value less than

and 98,916 less than

and 98,916 less than  . So symbolic maths is going to be needed (a shame since I had found tscount, an R package for analyzing count time series),

. So symbolic maths is going to be needed (a shame since I had found tscount, an R package for analyzing count time series), - a goodly 72,202 sequences are in sorted order, leaving 41,643 to go up and down,

- The least significant digit of the values in many sequences are a subset of the ten possible values. The following is a list of the number of unique least significant digits in the training sequences:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 1289 4692 6800 11589 15773 13701 7635 8644 10837 32885

After removing sequences containing fewer than 20 values (the -1 count)

-1 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 33398 764 3006 3171 6068 8930 7898 3690 5604 9073 32243

Lampros found Martin Rubey’s work on guessing formulas for sequences, which had an Open Source implementation using FriCAS (source code, which needs Steel Bank Common Lisp to build, which itself needs your OS to support 512 open files {OS X default is 256}).

Other software and papers include: the gfun package plus paper, sequence prediction in Mathematica and a Masters thesis on Inductive Inference of Integer Sequences.

These systems are all based on fitting, a potentially very complicated, polynomial to each sequence and achieve a success rate of around 20% on the complete OEIS.

What are the characteristics of the 80% for which a polynomial fit does not predict the next value? Perhaps there are not enough values specified in these sequence to fit the necessary polynomial. Perhaps the values grow at a faster rate than can be fitted by any polynomial expression, e.g., the Busy beaver function.

A 11:00-17:00 hackathon is not really enough time to get anything sensible up and running. People doing Masters projects had more hours and were managing to get around 20% correct.

The competition leaderboard currently has somebody with a score of 0.74. This is a big lead over everybody else. Am I being cynical by thinking the model might be reading the OEIS text to find the formula describing the sequence and then evaluating this?

Update

Comparing Computer Models Solving Number Series Problems provides an interesting review of systems using an AI based approach, i.e., trying to mimic what people do.

Recent Comments