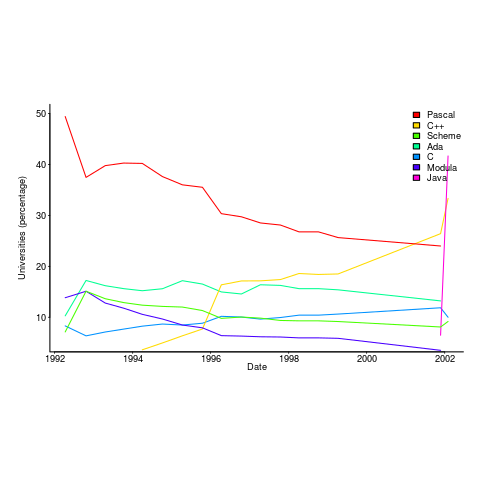

First language taught to undergraduates in the 1990s

The average new graduate is likely to do more programming during the first month of a software engineering job, than they did during a year as an undergraduate. Programming courses for undergraduates is really about filtering out those who cannot code.

Long, long ago, when I had some connection to undergraduate hiring, around 70-80% of those interviewed for a programming job could not write a simple 10-20 line program; I’m told that this is still true today. Fluency in any language (computer or human) takes practice, and the typical undergraduate gets very little practice (there is no reason why they should, there are lots of activities on offer to students and programming fluency is not needed to get a degree).

There is lots of academic discussion around which language students should learn first, and what languages they should be exposed to. I have always been baffled by the idea that there was much to be gained by spending time teaching students multiple languages, when most of them barely grasp the primary course language. When I was at school the idea behind the trendy new maths curriculum was to teach concepts, rather than rote learning (such as algebra; yes, rote learning of the rules of algebra); the concept of number-base was considered to be a worthwhile concept and us kids were taught this concept by having the class convert values back and forth, such as base-10 numbers to base-5 (base-2 was rarely used in examples). Those of us who were good at maths instantly figured it out, while everybody else was completely confused (including some teachers).

My view is that there is no major teaching/learning impact on the choice of first language; it is all about academic fashion and marketing to students. Those who have the ability to program will just pick it up, and everybody else will flounder and do their best to stay away from it.

Richard Reid was interested in knowing which languages were being used to teach introductory programming to computer science and information systems majors. Starting in 1992, he contacted universities roughly twice a year, asking about the language(s) used to teach introductory programming. The Reid list (as it became known), was regularly updated until Reid retired in 1999 (the average number of universities included in the list was over 400); one of Reid’s ex-students, Frances VanScoy, took over until 2006.

The plot below is from 1992 to 2002, and shows languages in the top with more than 3% usage in any year (code+data):

Looking at the list again reminded me how widespread Pascal was as a teaching language. Modula-2 was the language that Niklaus Wirth designed as the successor of Pascal, and Ada was intended to be the grown up Pascal.

While there is plenty of discussion about which language to teach first, doing this teaching is a low status activity (there is more fun to be had with the material taught to the final year students). One consequence is lack of any real incentive for spending time changing the course (e.g., using a new language). The Open University continued teaching Pascal for years, because material had been printed and had to be used up.

C++ took a while to take-off because of its association with C (which was very out of fashion in academia), and Java was still too new to risk exposing to impressionable first-years.

A count of the total number of languages listed, between 1992 and 2002, contains a few that might not be familiar to readers.

Ada Ada/Pascal Beta Blue C

1087 1 10 3 667

C/Java C/Scheme C++ C++/Pascal Eiffel

1 1 910 1 29

Fortran Haskell HyperTalk ISETL ISETL/C

133 12 2 30 1

Java Java/Haskell Miranda ML ML/Java

107 1 48 16 1

Modula-2 Modula-3 Oberon Oberon-2 ObjPascal

727 24 26 7 22

Orwell Pascal Pascal/C Prolog Scheme

12 2269 1 12 752

Scheme/ML Scheme/Turing Simula Smalltalk SML

1 1 14 33 88

Turing Visual-Basic

71 3 |

I had never heard of Orwell, a vanity language foisted on Oxford Mathematics and Computation students. It used to be common for someone in computing departments to foist their vanity language on students; it enabled them to claim the language was being used and stoked their ego. Is there some law that enables students to sue for damages?

The 1990s was still in the shadow of the 1980s fashion for functional programming (which came back into fashion a few years ago). Miranda was an attempt to commercialize a functional language compiler, with Haskell being an open source reaction.

I was surprised that Turing was so widely taught. More to do with the stature of where it came from (university of Toronto), than anything else.

Fortran was my first language, and is still widely used where high performance floating-point is required.

ISETL is a very interesting language from the 1960s that never really attracted much attention outside of New York. I suspect that Blue is BlueJ, a Java IDE targeting novices.

Want to be the coauthor of a prestigious book? Send me your bid

The corruption that pervades the academic publishing system has become more public.

There is now a website that makes use of an ingenious technique for helping people increase their paper count (as might be expected, the competitive China thought of it first). Want to be listed as the first author of a paper? Fees start at $500. The beauty of the scheme is that the papers have already been accepted by a journal for publication, so the buyer knows exactly what they are getting. Paying to be included as an author before the paper is accepted incurs the risk that the paper might not be accepted.

Measurement of academic performance is based on number of papers published, weighted by the impact factor of the journal in which they are published. Individuals seeking promotion and research funding need an appropriately high publication score; the ranking of university departments is based on the publications of its members. The phrase publish or perish aptly describes the process. As expected, with individual careers and departmental funding on the line, the system has become corrupt in all kinds of ways.

There are organizations who will publish your paper for a fee, 100% guaranteed, and you can even attend a scam conference (that’s not how the organizers describe them). Problem is, word gets around and the weighting given to publishing in such journals is very low (or it should be, not all of them get caught).

The horror being expressed at this practice is driven by the fact that money is changing hands. Adding a colleague as an author (on the basis that they will return the favor later) is accepted practice; tacking your supervisors name on to the end of the list of authors is standard practice, irrespective of any contribution that might have made (how else would a professor accumulate 100+ published papers).

I regularly receive emails from academics telling me they would like to work on this or that with me. If they look like proper researchers, I am respectful; if they look like an academic paper mill, my reply points out (subtly or otherwise) that their work is not of high enough standard to be relevant to industry. Perhaps I should send them a quote for having their name appear on a paper written by me (I don’t publish in academic journals, so such a paper is unlikely to have much value in the system they operate within); it sounds worth doing just for the shocked response.

I read lots of papers, and usually ignore the list of authors. If it looks like there is some interesting data associated with the work, I email the first author, and will only include the other authors in the email if I am looking to do a bit of marketing for my book or the paper is many years old (so the first author is less likely to have the data).

I continue to be amazed at the number of people who continue to strive to do proper research in this academic environment.

I wonder how much I might get by auctioning off the coauthoship of my software engineering book?

2019 in the programming language standards’ world

Last Tuesday I was at the British Standards Institute for a meeting of IST/5, the committee responsible for programming language standards in the UK.

There has been progress on a few issues discussed last year, and one interesting point came up.

It is starting to look as if there might be another iteration of the Cobol Standard. A handful of people, in various countries, have started to nibble around the edges of various new (in the Cobol sense) features. No, the INCITS Cobol committee (the people who used to do all the heavy lifting) has not been reformed; the work now appears to be driven by people who cannot let go of their involvement in Cobol standards.

ISO/IEC 23360-1:2006, the ISO version of the Linux Base Standard, has been updated and we were asked for a UK position on the document being published. Abstain seemed to be the only sensible option.

Our WG20 representative reported that the ongoing debate over pile of poo emoji has crossed the chasm (he did not exactly phrase it like that). Vendors want to have the freedom to specify code-points for use with their own emoji, e.g., pineapple emoji. The heady days, of a few short years ago, when an encoding for all the world’s character symbols seemed possible, have become a distant memory (the number of unhandled logographs on ancient pots and clay tablets was declining rapidly). Who could have predicted that the dream of a complete encoding of the symbols used by all the world’s languages would be dashed by pile of poo emoji?

The interesting news is from WG9. The document intended to become the Ada20 standard was due to enter the voting process in June, i.e., the committee considered it done. At the end of April the main Ada compiler vendor asked for the schedule to be slipped by a year or two, to enable them to get some implementation experience with the new features; oops. I have been predicting that in the future language ‘standards’ will be decided by the main compiler vendors, and the future is finally starting to arrive. What is the incentive for the GNAT compiler people to pay any attention to proposals written by a bunch of non-customers (ok, some of them might work for customers)? One answer is that Ada users tend to be large bureaucratic organizations (e.g., the DOD), who like to follow standards, and might fund GNAT to implement the new document (perhaps this delay by GNAT is all about funding, or lack thereof).

Right on cue, C++ users have started to notice that C++20’s added support for a system header with the name version, which conflicts with much existing practice of using a file called version to contain versioning information; a problem if the header search path used the compiler includes a project’s top-level directory (which is where the versioning file version often sits). So the WG21 committee decides on what it thinks is a good idea, implementors implement it, and users complain; implementors now have a good reason to not follow a requirement in the standard, to keep users happy. Will WG21 be apologetic, or get all high and mighty; we will have to wait and see.

Complexity is a source of income in open source ecosystems

I am someone who regularly uses R, and my interest in programming languages means that on a semi-regular basis spend time reading blog posts about the language. Over the last year, or so, I had noticed several patterns of behavior, and after reading a recent blog post things started to make sense (the blog post gets a lot of things wrong, but more of that later).

What are the patterns that have caught my attention?

Some background: Hadley Wickham is the guy behind some very useful R packages. Hadley was an academic, and is now the chief scientist at RStudio, the company behind the R language specific IDE of the same name. As Hadley’s thinking about how to manipulate data has evolved, he has created new packages, and has been very prolific. The term Hadley-verse was coined to describe an approach to data manipulation and program structuring, based around use of packages written by the man.

For the last nine-months I have noticed that the term Tidyverse is being used more regularly to describe what had been the Hadley-verse. And???

Another thing that has become very noticeable, over the last six-months, is the extent to which a wide range of packages now have dependencies on packages in the HadleyTidyverse. And???

A recent post by Norman Matloff complains about the Tidyverse’s complexity (and about the consistency between its packages; which I had always thought was a good design principle), and how RStudio’s promotion of the Tidyverse could result in it becoming the dominant R world view. Matloff has an academic world view and misses what is going on.

RStudio, the company, need to sell their services (their IDE is clunky and will be wiped out if a top of the range product, such as Jetbrains, adds support for R). If R were simple to use, companies would have less need to hire external experts. A widely used complicated library of packages is a god-send for a company looking to sell R services.

I don’t think Hadley Wickam intentionally made things complicated, any more than the creators of the Microsoft server protocols added interdependencies to make life difficult for competitors.

A complex package ecosystem was probably not part of RStudio’s product vision, at least for many years. But sooner or later, RStudio management will have realised that simplicity and ease of use is not in their interest.

Once a collection of complicated packages exist, it is in RStudio’s interest to get as many other packages using them, as quickly as possible. Infect the host quickly, before anybody notices; all the while telling people how much the company is investing in the community that it cares about (making lots of money from).

Having this package ecosystem known as the Hadley-verse gives too much influence to one person, and makes it difficult to fire him later. Rebranding as the Tidyverse solves these problems.

Matloff accuses RStudio of monopoly behavior, I would have said they are fighting for survival (i.e., creating an environment capable of generating the kind of income a VC funded company is expected to make). Having worked in language environments where multiple, and incompatible, package ecosystems existed, I can see advantages in there being a monopoly. Matloff is also upset about a commercial company swooping in to steal their precious, a common academic complaint (academics swooping in to steal ideas from commercially developed software is, of course, perfectly respectable). Matloff also makes claims about teachability of programming that are not derived from any experimental evidence, but then everybody makes claims about programming languages without there being any experimental evidence.

RStudio management rode in on the data science wave, raising money from VCs. The wave is subsiding and they now need to appear to have a viable business (so they can be sold to a bigger fish), which means there has to be a visible market they can sell into. One way to sell in an open source environment is for things to be so complicated, that large companies will pay somebody to handle the complexity.

How much is a 1-hour investment today worth a year from now?

Today, I am thinking of investing 1-hour of effort adding more comments to my code; how much time must this investment save me X-months from now, for today’s 1-hour investment to be worthwhile?

Obviously, I must save at least 1-hour. But, the purpose of making an investment is to receive a greater amount at a later time; ‘paying’ 1-hour to get back 1-hour is a poor investment (unless I have nothing else to do today, and I’m likely to be busy in the coming months).

The usual economic’s based answer is based on compound interest, the technique your bank uses to calculate how much you owe them (or perhaps they owe you), i.e., the expected future value grows exponentially at some interest rate.

Psychologists were surprised to find that people don’t estimate future value the way economists do. Hyperbolic discounting provides a good match to the data from experiments that asked subjects to value future payoffs. The form of the equation used by economists is:  , while hyperbolic discounting has the form

, while hyperbolic discounting has the form  , where:

, where:  is a constant, and

is a constant, and  the period of time.

the period of time.

The simple economic approach does not explicitly include the risk that one of the parties involved may cease to exist. Including risk is non-trivial, banks handle the risk that you might disappear by asking for collateral, or adding something to the interest rate charged.

The fact that humans, and some other animals, have been found to use hyperbolic discounting suggests that evolution has found this approach, to discounting time, increases the likelihood of genes being passed on to the next generation. A bird in the hand is worth two in the bush.

How do software developers discount investment in software engineering projects?

The paper Temporal Discounting in Technical Debt: How do Software Practitioners Discount the Future? describes a study that specifies a decision that has to be made and two options, as follows:

“You are managing an N-years project. You are ahead of schedule in the current iteration. You have to decide between two options on how to spend our upcoming week. Fill in the blank to indicate the least amount of time that would make you prefer Option 2 over Option 1.

- Option 1: Implement a feature that is in the project backlog, scheduled for the next iteration. (five person days of effort).

- Option 2: Integrate a new library (five person days effort) that adds no new functionality but has a 60% chance of saving you person days of effort over the duration of the project (with a 40% chance that the library will not result in those savings).

”

Subjects are then asked six questions, each having the following form (for various time frames):

“For a project time frame of 1 year, what is the smallest number of days that would make you prefer Option 2? ___”

The experiment is run twice, using professional developers from two companies, C1 and C2 (23 and 10 subjects, respectively), and the data is available for download 🙂

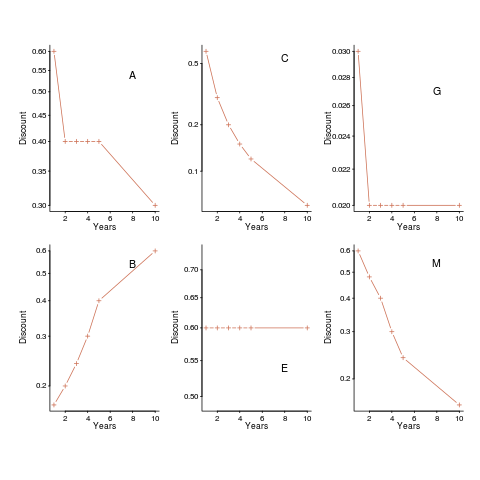

The following plot shows normalised values given by some of the subjects from company C1, for the various time periods used (y-axis shows  ). On a log scale, values estimated using the economists exponential approach would form a straight line (e.g., close to the first five points of subject M, bottom right), and values estimated using the hyperbolic approach would have the concave form seen for subject C (top middle) (code+data).

). On a log scale, values estimated using the economists exponential approach would form a straight line (e.g., close to the first five points of subject M, bottom right), and values estimated using the hyperbolic approach would have the concave form seen for subject C (top middle) (code+data).

Subject B is asking for less, not more, over a longer time period (several other subjects have the same pattern of response). Why did Subject E (and most of subject G’s responses) not vary with time? Perhaps they were tired and were not willing to think hard about the problem, or perhaps they did not think the answer made much difference. The subjects from company C2 showed a greater amount of variety. Company C1 had some involvement with financial applications, while company C2 was involved in simulations. Did this domain knowledge spill over into company C1’s developers being more likely to give roughly consistent answers?

The experiment was run online, rather than an experimenter being in the room with subjects. It is possible that subjects would have invested more effort if a more formal setting, with an experimenter who had made the effort to be present. Also, if an experimenter had been present, it would have been possible to ask question to clarify any issues.

Both exponential and hyperbolic equations can be fitted to the data, but given the diversity of answers, it is difficult to put any weight in either regression model. Some subjects clearly gave responses fitting a hyperbolic equation, while others gave responses fitted approximately well by either approach, and other subjects used. It was possible to fit the combined data from all of company C1 subjects to a single hyperbolic equation model (the most significant between subject variation was the value of the intercept); no such luck with the data from company C2.

I’m very please to see there has been a replication of this study, but the current version of the paper is a jumble of ideas, and is thin on experimental procedure. I’m sure it will improve.

What do we learn from this study? Perhaps that developers need to learn something about calculating expected future payoffs.

Medieval guilds: a tax collection bureaucracy

The medieval guild is sometimes held up as the template for an institution dedicated to maintaining high standards, and training the next generation of craftsmen.

“The European Guilds: An economic analysis” by Sheilagh Ogilvie takes a chainsaw (i.e., lots of data) to all the positive things that have been said about medieval guilds (apart from them being a money making machine for those on the inside).

Guilds manipulated markets (e.g., drove down the cost of input items they needed, and kept the prices they charged high), had little or no interest in quality, charged apprentices for what little training they received, restricted entry to their profession (based on the number of guild masters the local population could support in a manner expected by masters), and did not hesitate to use force to enforce the rules of the guild (should a member appear to threaten the livelihood of other guild members).

Guild wars is not the fiction of an online game, guilds did go to war with each other.

Given their focus on maximizing income, rather than providing customer benefits, why did guilds survive for so many centuries? Guilds paid out significant sums to influence those in power, i.e., bribes. Guilds paid annual sums for the exclusive rights to ply their trade in geographical areas; it’s all down on Vellum.

Guilds provided the bureaucracy needed to collect money from the populace, i.e., they were effectively tax collectors. Medieval rulers had a high turn-over, and most were not around long enough to establish a civil service. In later centuries, the growth of a country’s population led to the creation of government departments, that were stable enough to perform tax collecting duties more efficiently that guilds; it was the spread of governments capable of doing their own tax collecting that killed off guilds.

A zero-knowledge proofs workshop

I was at the Zero-Knowledge proofs workshop run by BinaryDistict on Monday and Tuesday. The workshop runs all week, but is mostly hacking for the remaining days (hacking would be interesting if I had a problem to code, more about this at the end).

Zero-knowledge proofs allow person A to convince person B, that A knows the value of x, without revealing the value of x. There are two kinds of zero-knowledge proofs: an interacting proof system involves a sequence of messages being exchanged between the two parties, and in non-interactive systems (the primary focus of the workshop), there is no interaction.

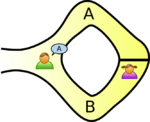

The example usually given, of a zero-knowledge proof, involves Peggy and Victor. Peggy wants to convince Victor that she knows how to unlock the door dividing a looping path through a tunnel in a cave.

The ‘proof’ involves Peggy walking, unseen by Victor, down path A or B (see diagram below; image from Wikipedia). Once Peggy is out of view, Victor randomly shouts out A or B; Peggy then has to walk out of the tunnel using the path Victor shouted; there is a 50% chance that Peggy happened to choose the path selected by Victor. The proof is iterative; at the end of each iteration, Victor’s uncertainty of Peggy’s claim of being able to open the door is reduced by 50%. Victor has to iterate until he is sufficiently satisfied that Peggy knows how to open the door.

As the name suggests, non-interactive proofs do not involve any message passing; in the common reference string model, a string of symbols, generated by person making the claim of knowledge, is encoded in such a way that it can be used by third-parties to verify the claim of knowledge. At the workshop we got an overview of zk-SNARKs (zero-knowledge succinct non-interactive argument of knowledge).

The ‘succinct’ component of zk-SNARK is what has made this approach practical. When non-interactive proofs were first proposed, the arguments of knowledge contained around one-terabyte of data; these days common reference strings are around a kilobyte.

The fact that zero-knowledge ‘proof’s are possible is very interesting, but do they have practical uses?

The hackathon aspect of the workshop was designed to address the practical use issue. The existing zero-knowledge proofs tend to involve the use of prime numbers, or the factors of very large numbers (as might be expected of a proof system that is heavily based on cryptographic techniques). Making use of zero-knowledge proofs requires mapping the problem to a form that has a known solution; this is very hard. Existing applications involve cryptography and block-chains (Zcash is a cryptocurrency that has an option that provides privacy via zero-knowledge proofs), both heavy users of number theory.

The workshop introduced us to two languages, which could be used for writing zero-knowledge applications; ZoKrates and snarky. The weekend before the workshop, I tried to install both languages: ZoKrates installed quickly and painlessly, while I could not get snarky installed (I was told that the first two hours of the snarky workshop were spent getting installs to work); I also noticed that ZoKrates had greater presence than snarky on the web, in the form of pages discussing the language. It seemed to me that ZoKrates was the market leader. The workshop presenters included people involved with both languages; Jacob Eberhardt (one of the people behind ZoKrates) gave a great presentation, and had good slides. Team ZoKrates is clearly the one to watch.

As an experienced hack attendee, I was ready with an interesting problem to solve. After I explained the problem to those opting to use ZoKrates, somebody suggested that oblivious transfer could be used to solve my problem (and indeed, 1-out-of-n oblivious transfer does offer the required functionality).

My problem was: Let’s say I have three software products, the customer has a copy of all three products, and is willing to pay the license fee to use one of these products. However, the customer does not want me to know which of the three products they are using. How can I send them a product specific license key, without knowing which product they are going to use? Oblivious transfer involves a sequence of message exchanges (each exchange involves three messages, one for each product) with the final exchange requiring that I send three messages, each containing a separate product key (one for each product); the customer can only successfully decode the product-specific message they had selected earlier in the process (decoding the other two messages produces random characters, i.e., no product key).

Like most hackathons, problem ideas were somewhat contrived (a few people wanted to delve further into the technical details). I could not find an interesting team to join, and left them to it for the rest of the week.

There were 50-60 people on the first day, and 30-40 on the second. Many of the people I spoke to were recent graduates, and half of the speakers were doing or had just completed PhDs; the field is completely new. If zero-knowledge proofs take off, decisions made over the next year or two by the people at this workshop will impact the path the field follows. Otherwise, nothing happens, and a bunch of people will have interesting memories about stuff they dabbled in, when young.

Lehman ‘laws’ of software evolution

The so called Lehman laws of software evolution originated in a 1968 study, and evolved during the 1970s; the book “Program Evolution: processes of software change” by Lehman and Belady was published in 1985.

The original work was based on measurements of OS/360, IBM’s flagship operating system for the computer industries flagship computer. IBM dominated the computer industry from the 1950s, through to the early 1980s; OS/360 was the Microsoft Windows, Android, and iOS of its day (in fact, it had more developer mind share than any of these operating systems).

In its day, the Lehman dataset not only bathed in reflected OS/360 developer mind-share, it was the only public dataset of its kind. But today, this dataset wouldn’t get a second look. Why? Because it contains just 19 measurement points, specifying: release date, number of modules, fraction of modules changed since the last release, number of statements, and number of components (I’m guessing these are high level programs or interfaces). Some of the OS/360 data is plotted in graphs appearing in early papers, and can be extracted; some of the graphs contain 18, rather than 19, points, and some of the values are not consistent between plots (extracted data); in later papers Lehman does point out that no statistical analysis of the data appears in his work (the purpose of the plots appears to be decorative, some papers don’t contain them).

One of Lehman’s early papers says that “… conclusions are based, comes from systems ranging in age from 3 to 10 years and having been made available to users in from ten to over fifty releases.“, but no other details are given. A 1997 paper lists module sizes for 21 releases of a financial transaction system.

Lehman’s ‘laws’ started out as a handful of observations about one very large software development project. Over time ‘laws’ have been added, deleted and modified; the Wikipedia page lists the ‘laws’ from the 1997 paper, Lehman retired from research in 2002.

The Lehman ‘laws’ of software evolution are still widely cited by academic researchers, almost 50-years later. Why is this? The two main reasons are: the ‘laws’ are sufficiently vague that it’s difficult to prove them wrong, and Lehman made a large investment in marketing these ‘laws’ (e.g., publishing lots of papers discussing these ‘laws’, and supervising PhD students who researched software evolution).

The Lehman ‘laws’ are not useful, in the sense that they cannot be used to make predictions; they apply to large systems that grow steadily (i.e., the kind of systems originally studied), and so don’t apply to some systems, that are completely rewritten. These ‘laws’ are really an indication that software engineering research has been in a state of limbo for many decades.

PCTE: a vestige of a bygone era of ISO standards

The letters PCTE (Portable Common Tool Environment) might stir vague memories, for some readers. Don’t bother checking Wikipedia, there is no article covering this PCTE (although it is listed on the PCTE acronym page).

The ISO/IEC Standard 13719 Information technology — Portable common tool environment (PCTE) —, along with its three parts, has reached its 5-yearly renewal time.

The PCTE standard, in itself, is not interesting; as far as I know it was dead on arrival. What is interesting is the mindset, from a bygone era, that thought such a standard was a good idea; and, the continuing survival of a dead on arrival standard sheds an interesting light on ISO standards in the 21st century.

PCTE came out of the European Union’s first ESPRIT project, which ran from 1984 to 1989. Dedicated workstations for software developers were all the rage (no, not those toy microprocessor-based thingies, but big beefy machines with 15 inch displays, and over a megabyte of memory), and computer-aided software engineering (CASE) tools were going to provide a huge productivity boost.

PCTE is a specification for a tool interface, i.e., an interface whereby competing CASE tools could provide data interoperability. The promise of CASE tools never materialized, and they faded away, removing the need for an interface standard.

CASE tools and PCTE are from an era where lots of managers still thought that factory production methods could be applied to software development.

PCTE was a European-funded project coordinated by a (at the time) mainframe manufacturer. Big is beautiful, and specifications with clout are ISO standards (ECMA was used to fast track the document).

At the time Ada was the language that everybody was going to be writing in the future; so, of course, there is an Ada binding (there is also a C one, cannot ignore reality too much).

Why is there still an ISO standard for PCTE? All standards are reviewed every 5-years, countries have to vote to keep them, or not, or abstain. How has this standard managed to ‘live’ so long?

One explanation is that by being dead on arrival, PCTE never got the chance to annoy anybody, and nobody got to know anything about it. Standard’s committees tend to be content to leave things as they are; it would be impolite to vote to remove a document from the list of approved standards, without knowing anything about the subject area covered.

The members of IST/5, the British Standards committee responsible (yes, it falls within programming languages), know they know nothing about PCTE (and that its usage is likely to be rare to non-existent) could vote ABSTAIN. However, some member countries of SC22 might vote YES, because while they know they know nothing about PCTE, they probably know nothing about most of the documents, and a YES vote does not require any explanation (no, I am not suggesting some countries have joined SC22 to create a reason for flunkies to spend government money on international travel).

Prior to the Internet, ISO standards were only available in printed form. National standards bodies were required to hold printed copies of ISO standards, ready for when an order to arrive. When a standard having zero sales in the last 5-years, came up for review a pleasant person might show up at the IST/5 meeting (or have a quiet word with the chairman beforehand); did we really want to vote to keep this document as a standard? Just think of the shelf space (I never heard them mention the children dead trees). Now they have pdfs occupying rotating rust.

Cognitive capitalism chapter reworked

The Cognitive capitalism chapter of my evidence-based software engineering book took longer than expected to polish; in fact it got reworked, rather than polished (which still needs to happen, and there might be more text moving from other chapters).

Changing the chapter title, from Economics to Cognitive capitalism, helped clarify lots of decisions about the subject matter it ought to contain (the growth in chapter page count is more down to material moving from other chapters, than lots of new words from me).

I over-spent time down some interesting rabbit holes (e.g., real options), before realising that no public data was available, and unlikely to be available any time soon. Without data, there is not a lot that can be said in a data driven book.

Social learning is a criminally under researched topic in software engineering. Some very interesting work has been done by biologists (e.g., Joseph Henrich, and Kevin Laland), in the last 15 years; the field has taken off. There is a huge amount of social learning going on in software engineering, and virtually nobody is investigating it.

As always, if you know of any interesting software engineering data, please let me know.

Next, the Ecosystems chapter.

Recent Comments