CPU frequency not relevant to SPEC benchmark performance

Despite the end of Dennard scaling around 2005-7 computer performance, as measured by the SPEC cpu benchmarks, continues to improve. What is driving this ongoing increase in performance, given that cpu clock rates have stopped increasing?

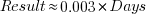

The plot below shows 9,161 results from the SPEC CPU integer benchmark, plus the fitted regression line  (code+data):

(code+data):

There is a scattering of benchmark results because manufacturers offer systems having a range of performance.

Possible factors driving the ongoing increases in system performance include increased DRAM-memory bandwidth, and cpu improvements such as larger caches and more accurate branch prediction. While Moore’s law (i.e., rate of growth of the number of transistors on a chip) has slowed down a lot, the number of transistors in a processor chip has continued to increase (many of these transistors have been used to build chips that contain multiple cpu cores).

The SPEC benchmark result data includes a lot of information about the system that ran the benchmarks, including: processor family/model, number of cpu cores, clock frequency, amount of memory installed and its type.

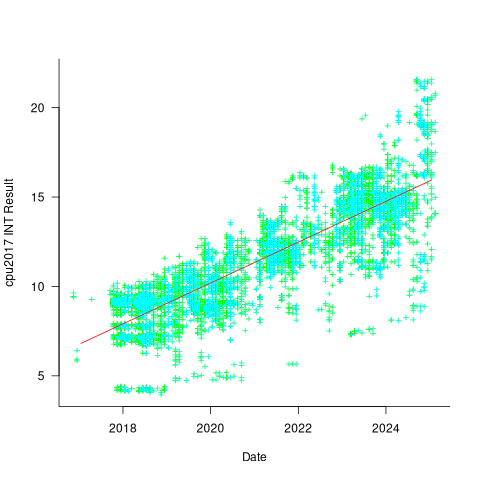

Results from SPEC CPU2017, the current version of the benchmark, are available from the start of 2017 to now. The following analysis uses these results. Results from the SPEC CPU2006 benchmark are also available, and a regression model fitted to the results from the 780 systems that ran both benchmarks, gives the mapping from CPU INT 2006 to CPU INT 2017 as:  .

.

The processor information in the results file usually specifies family name plus model number/name. The model information usually correlates with clock frequency, perhaps cache size, or gpu support; some examples below.

AMD EPYC 4464P AMD EPYC 4564P

AMD Ryzen 9 7950X AMD Ryzen 7 5800X

Intel Xeon Platinum 8490H Intel Xeon Gold 6438N

Intel Xeon E3-1220 v3 Intel Xeon E5-2697 v3 |

The family name is sufficient for an initial analysis. Details of any cache size differences between models can always be included in a later analysis. The following table shows the number of processor x86 based families present in the 2017 INT results (total 9,161):

AMD EPYC AMD Ryzen Intel

1475 7 1

Intel Celeron Intel Core i3 Intel Core i5

16 31 2

Intel Core i7 Intel Pentium Intel Xeon

1 30 605

Intel Xeon Bronze Intel Xeon D Intel Xeon E3

167 12 16

Intel Xeon E5 Intel Xeon E7 Intel Xeon Gold

3 2 3994

Intel Xeon Platinum Intel Xeon Silver Intel Xeon W

1822 969 8 |

The memory information usually includes total bytes, number of memory sticks and interface standard (e.g., DDR2/3/4/5); some examples below.

64 GB (2 x 32 GB 2Rx4 PC5-5600B-R, running at 5200)

64 GB (2 x 32 GB 2Rx8 PC4-3200AA-E)

256 GB (8*1GB DDR2-400 DIMMS per 4 core module)

192 GB (4 x 12 x 4 GB DDR3-1333R, ECC, CL9)

32 GB (8 x 4 GB Dual-rank PC2-6400 CL5-5-5 FB-DIMMs)

24 GB (6 x 4 GB DDR3-1333 downclocked to 1066 MHz) |

The memory bandwidth can be calculated from the interface standard used. The names of modern DRAM interface standards start with either DDR or PC, and a number, a hyphen and then another number. The values appearing in the SPEC results don’t always follow the naming rules listed in the standard (e.g., last number of a PC name using the corresponding DDR number), and in a few cases a digit was dropped from the last number. Where possible the ‘obvious’ edits were made (sometimes values were just wrong), see code for details. The following table shows the number of interface standards represented in the 2017 CPU INT results (total 9,161; in the 2006 results DDR names predominated):

PC4-2400 PC4-2666 PC4-2933 PC4-3200 PC4-4800 PC5-11200 PC5-12800

26 2248 2163 2080 6 2 3

PC5-4800 PC5-5200 PC5-5600 PC5-6400 PC5-8 PC5-8800

1735 5 653 233 2 5 |

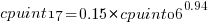

Once the memory is identified, its bandwidth can be looked up (bespoke memory stick clock rates were ignored). Fitting a regression model to the data, with the CPU INT (cpu integer benchmark) result as the outcome, we get (using a multiplicative model allows each factor to have a percentage impact; code+data):

where:  is the memory bandwidth in megabytes per second,

is the memory bandwidth in megabytes per second,  is cpu frequency in MHz, and

is cpu frequency in MHz, and  is the fitted constant for each processor family.

is the fitted constant for each processor family.

The cpu frequency varies between 1.7 and 4.7 GHz (a ratio of 1:2.8), the memory bandwidth between 19,200 and 51,200 MB/s (a ratio of 1:2.7), and processor family performance impact ratio was 1:2.2. Given the fitted power laws, this range of cpu frequencies could impact performance by around 22%, while the range of memory bandwidth could impact performance by a factor of two.

This fitted model implies that cpu frequency changes, over the range supported by systems since 2017, have almost no impact on the performance of integer-based programs, i.e., no floating point.

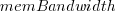

I thought there might be a correlation between memory bandwidth and cpu frequency (because vendors would use faster memory in systems with faster cpus). The plot below shows CPU frequency against memory bandwidth (both axis use linear scales), plus a fitted regression line in red (code+data):

I was wrong. There does not appear to be any connection between a system’s cpu frequency and its memory bandwidth.

These days, most x86 chips include multiple processors, with each processor taking a share of memory bandwidth. Increasing memory bandwidth is essential, if all cores are to be kept busy.

The SPEC CPU benchmark measures the performance of a single processor. If only one of the cpu cores available on a system is being used, that core has the benefit of memory bandwidth that usually has to be shared.

To what extent is a single core benchmark relevant today? I suspect that most programs run on a single core, but developers sometimes attempt to spread cpu intensive programs over multiple cores. As always, data is needed.

The SPEC benchmark is useful for cpu designers (the original target market) and compiler writers wanting to measure the impact of fancy new optimizations.

If you bought a high-end peecee in 2018, SEVEN years later, you can buy a high-end one today with about twice the performance. Back in the mid-1980s to mid-2000s, you got twice the performance every TWO years, as clock speeds went from small numbers of MHz to small numbers of Ghz.

It was rather silly. At one point I had THREE generations of discarded peecees in a closet that had been upgraded to far most powerful machines, every single one of which ran Windows NT just fine. (I found someone to give them to who made good use of them.)

We live in a rather different age. Sigh.

Also different is, as you imply, a lot of recent improvements are architectural: our CPU designer friends are busting their collective butts without much help from their silicon-specialist friends. This is a laudable thing, I think.

Also of interest is that there’s now interest in instruction per Watt, instead of just instructions per second. Apple perhaps figured this out first, but Intel followed, realizing that a cycle-greedy user (with paralllelizable applications) would rather have two “efficiency” cores than one “performance” core, even if that performance core was running two threads. (Translation: “hyperthreading” was more than a bit of a snore.)

@David in Tokyo

I remember when the performance difference between successive generations of computers was very visible, e.g., seeing the speed at which the names of the files being compiled scrolled up the screen. Originally a filename would appear and sometime later the next filename, the pause between filenames got shorter and shorter, then the speed at which they scrolled up the screen got faster and faster, and today they zip by and are gone.

I suspect that most of the cpu performance gains are coming from bigger caches. The cache data in the SPEC results will take some untangling, which I will get around to eventually.

It would be very interesting to compare the power consumed by various systems running a benchmark. However, DVFS makes it difficult to accurately measure power consumed. SPEC have a power benchmark, but don’t publish any results.

To watch the machines get faster, I wrote a Conway Life program in 386 assembler that calculated 30 cells in parallel and then block transfered the data to the VGA controller, displaying one cell per VGA dot.

As a dyed-in-the-wool assember programmer, I was really irritated with myself when I coded the parallel addition stuff in C/C++ and noticed a more efficient way of implementing said stuff that I’d never have noticed just thinking about it/coding it in assembler.

There’s actually some relevance to your next post here, though, in that it crosses my mind that for most of what most people do, there’s no _functional_ difference with new generations of hardware. My SO is happily using my old first generation Surface Go, which replaced a seriously old Dell laptop that finally died. I play Go with my peecee, so I stress the graphics card something fierce, but other than Go, the music, language study, blathering on the internet would be identical with a many-generations back peecee. (Oh, yes. I’m doing some multi-corpus Japanese text stuff (total of 400,000 pages of text) that needs a reasonable amount of memory, but processor speed isn’t an issue.)

@David in Tokyo

LLMs have made some new generations of hardware relevant again. Even tiny models are hundreds of megabytes, with the much more usable models being in the tens of gigabytes. Anybody looking to run LLMs on their own machine are going to need huge amounts of fast memory. A lot of the high LLM performance on new Apple hardware actually comes from a design that supports really high memory bandwidth.