Small business programs: A dataset in the research void

My experience is that most of the programs created within organizations are very short, i.e., around 50–100 lines. Sometimes entire businesses are run using many short programs strung together in various ways. These short programs invariably make extensive use of the functionality provided by a much larger package that handles all the complicated stuff.

In the software development world, these short programs are likely to be shell scripts, but in the much larger ecosystem that is the business world these programs will be written in what used to be called a fourth generation language (4GL). These 4GLs are essentially domain specific languages for specific business tasks, such as report generation, or database query products, and for some time now spreadsheets.

The business software ecosystem is usually only studied by researchers in business schools, but short programs, business or otherwise, are rarely studied by any researchers. The source of such short programs is rarely publicly available; even if the information is not commercially confidential, the program likely addresses one group’s niche problem which is of no interest to anybody else, i.e., there is no rationale to publishing it. If source were available, there might not be enough of it to do any significant analysis.

I recently came across Clive Wrigley’s 1988 PhD thesis, which attempts to build a software estimation model. It contains summary data of 26 transaction processing systems written in the FOCUS language (an automated code generator).

For many organizations, there is a fundamental difference between business related problems and scientific/engineering problems, in that business problems tend to involve simple operations on lots of distinct data items (e.g., payroll calculation for each company employee), while scientific/engineering often involves a complicated formula operating on one set of data. There are exceptions.

4GLs enable technically proficient business users to create and maintain good enough applications without needing software engineering skills (yes, many do create spaghetti code), because they are not writing thousands of lines of code. The applications often contain many semi-self-contained subcomponents, which can be shared or swapped in/out. The small size makes it easier to change quickly, and there is direct access to the business users, it’s an agile process decades before this process took off in the world of non-4GL languages.

A major claim made by fans of 4GL is that it is much cheaper to create applications equivalent to those created using a 3GL, e.g., Cobol/C/C++/Java/Python/etc. I would agree that this true for small applications that fit the use-case addressed by a particular 4GL, but I think the domain specific nature of a 4GL will limit what can be done and likely need to be done in larger applications.

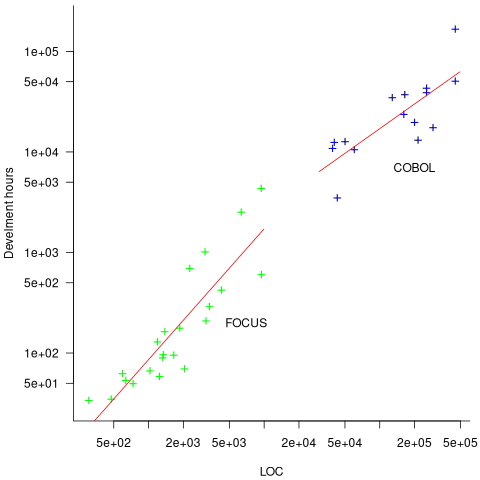

How do 4GL applications written in FOCUS compare against application written in Cobol? A 1987 paper by Chris Kemerer provides some manpower/LOC data for Cobol applications. I have no information on the amount of functionality in any of the applications. The plot below shows developer hours consumed creating 26 systems containing a given number of lines of code for FOCUS (green) and 15 COBOL (blue) programs, with fitted regression models in red (code+data):

The two samples of applications differ by two orders of magnitude in LOC and developer hours, however, there is no information on the functionality provided by the applications.

I’ve seen many mini-systems in my time to – especially those driving, or driven by, Excel.

In some ways this may be the future of coding. In more and more jobs some big system does most of the work (think ERP, CRM, etc.) and little bits of end-user script fill in the gaps. Its one of the ways that every job is becoming a coding job.

As to that the lo-code and no-code solutions where the scripts are recorded with a mouse (and which may not be portable to another version let alone a competitor) and the future looks small.

On the one hand that suggests we need more research here. It also suggests worries, there is no source control over them, people leave the scripts are unmanaged, and imagine might happens in 2035 when someone realises many of these systems are using long time counting and they all needed checking.

On the other hand, does it matter? Most of these scripts are essentially throw away. Although I suspect a few will rise to the point of being business critical.

@Allan Kelly

Short plumbing code is ideal fodder for LLM code generation.

I’m not sure what the useful output from a research program focusing on plumbing code might be. Yes, lots of stats on code characteristics and API calls could be produced, which might be of user to the vendor looking to improve their product, but where is the benefit to the user/developer.

Yes, business analyst written/maintained code is likely to be a tangled mess. But where is the incentive for them to learn some software engineering practices? The situation is the same as that faced by researchers who code.

In theory the scripts are throw away, but in practice they sometimes contain lots of crucial domain specific business knowledge; think legacy Cobol that has to be kept working.