Source code discovery, skipping over the legal complications

The 2020 US elections introduced the issue of source code discovery, in legal cases, to a wider audience. People wanted to (and still do) check that the software used to register and count votes works as intended, but the companies who wrote the software wouldn’t make it available and the courts did not compel them to do so.

I was surprised to see that there is even a section on “Transfer of or access to source code” in the EU-UK trade and cooperation agreement, agreed on Christmas Eve.

I have many years of experience in discovering problems in the source code of programs I did not write. This experience derives from my time as a compiler implementer (e.g., a big customer is being held up by a serious issue in their application, and the compiler is being blamed), and as a static analysis tool vendor (e.g., managers want to know about what serious mistakes may exist in the code of their products). In all cases those involved wanted me there, I could talk to some of those involved in developing the code, and there were known problems with the code. In court cases, the defence does not want the prosecution looking at the code, and I assume that all conversations with the people who wrote the code goes via the lawyers. I have intentionally stayed away from this kind of work, so my practical experience of working on legal discovery is zero.

The most common reason companies give for not wanting to make their source code available is that it contains trade-secrets (they can hardly say that it’s because they don’t want any mistakes in the code to be discovered).

What kind of trade-secrets might source code contain? Most code is very dull, and for some programs the only trade-secret is that if you put in the implementation effort, the obvious way of doing things works, i.e., the secret sauce promoted by the marketing department is all smoke and mirrors (I have had senior management, who have probably never seen the code, tell me about the wondrous properties of their code, which I had seen and knew that nothing special was present).

Comments may detail embarrassing facts, aka trade-secrets. Sometimes the code interfaces to a proprietary interface format that the company wants to keep secret, or uses some formula that required a lot of R&D (management gets very upset when told that ‘secret’ formula can be reverse engineered from the executable code).

Why does a legal team want access to source code?

If the purpose is to check specific functionality, then reading the source code is probably the fastest technique. For instance, checking whether a particular set of input values can cause a specific behavior to occur, or tracing through the logic to understand the circumstances under which a particular behavior occurs, or in software patent litigation checking what algorithms or formula are being used (this is where trade-secret claims appear to be valid).

If the purpose is a fishing expedition looking for possible incorrect behaviors, having the source code is probably not that useful. The quantity of source contained in modern applications can be huge, e.g., tens to hundreds of thousands of lines.

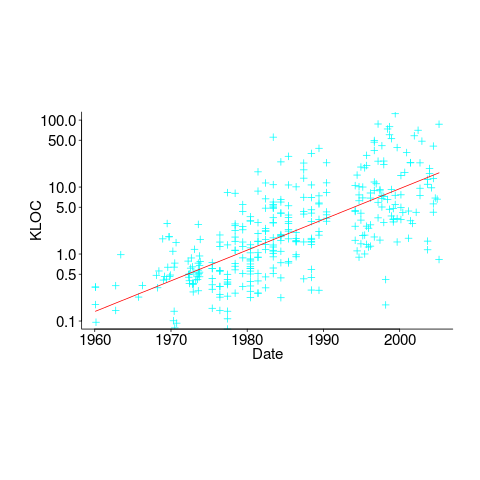

In ancient times (i.e., the 1970s and 1980s) programs were short (because most computers had tiny amounts of memory, compared to post-2000), and it was practical to read the source to understand a program. Customer demand for more features, and the fact that greater storage capacity removed the need to spend time reducing code size, means that source code ballooned. The following plot shows the lines of code contained in the collected algorithms of the Transactions on Mathematical Software, the red line is a fitted regression model of the form:  (code+data):

(code+data):

How, by reading the source code, does anybody find mistakes in a 10+ thousand line program? If the program only occasionally misbehaves, finding a coding mistake by reading the source is likely to be very very time-consuming, i.e, months. Work it out yourself: 10K lines of code is around 200 pages. How long would it take you to remember all the details and their interdependencies of a detailed 200-page technical discussion well enough to spot an inconsistency likely to cause a fault experience? And, yes, the source may very well be provided as a printout, or as a pdf on a protected memory stick.

From my limited reading of accounts of software discovery, the time available to study the code may be just days or maybe a week or two.

Reading large quantities of code, to discover possible coding mistakes, are an inefficient use of human time resources. Some form of analysis tool might help. Static analysis tools are one option; these cost money and might not be available for the language or dialect in which the source is written (there are some good tools for C because it has been around so long and is widely used).

Character assassination, or guilt by innuendo is another approach; the code just cannot be trusted to behave in a reasonable manner (this approach is regularly used in the software business). Software metrics are deployed to give the impression that it is likely that mistakes exist, without specifying specific mistakes in the code, e.g., this metric is much higher than is considered reasonable. Where did these reasonable values come from? Someone, somewhere said something, the Moon aligned with Mars and these values became accepted ‘wisdom’ (no, reality is not allowed to intrude; the case is made by arguing from authority). McCabe’s complexity metric is a favorite, and I have written how use of this metric is essentially accounting fraud (I have had emails from several people who are very unhappy about me saying this). Halstead’s metrics are another favorite, and at least Halstead and others at the time did some empirical analysis (the results showed how ineffective the metrics were; the metrics don’t calculate the quantities claimed).

The software development process used to create software is another popular means of character assassination. People seem to take comfort in the idea that software was created using a defined process, and use of ad-hoc methods provides an easy target for ridicule. Some processes work because they include lots of testing, and doing lots of testing will of course improve reliability. I have seen development groups use a process and fail to produce reliable software, and I have seen ad-hoc methods produce reliable software.

From what I can tell, some expert witnesses are chosen for their ability to project an air of authority and having impressive sounding credentials, not for their hands-on ability to dissect code. In other words, just the kind of person needed for a legal strategy based on character assassination, or guilt by innuendo.

What is the most cost-effective way of finding reliability problems in software built from 10k+ lines of code? My money is on fuzz testing, a term that should send shivers down the spine of a defense team. Source code is not required, and the output is a list of real fault experiences. There are a few catches: 1) the software probably to be run in the cloud (perhaps the only cost/time effective way of running the many thousands of tests), and the defense is going to object over licensing issues (they don’t want the code fuzzed), 2) having lots of test harnesses interacting with a central database is likely to be problematic, 3) support for emulating embedded cpus, even commonly used ones like the Z80, is currently poor (this is a rapidly evolving area, so check current status).

Fuzzing can also be used to estimate the numbers of so-far undetected coding mistakes.

Not only do you not have much time, you may also find yourself in a locked faraday cage with no s/w tools at your disposal beyond a simple editor. At any rate, you may find Michael Barr’s account interesting (https://embeddedgurus.com/barr-code/2013/10/an-update-on-toyota-and-unintended-acceleration/).

@Nemo

That Toyota case involved four people analysing the code for 18 months. But there was over a million lines across 4k+ files. What a task. I once spent 15+ months as an advisor on the EU-Microsoft competition case, we had secure laptops and could work from home a lot of the time, but even so it was very draining.

It looks like they did find some serious problems in the code, but they still threw in the character assassination; I am guessing this was a belt and braces legal strategy.

A few years ago, on the safety critical mailing list, I poked some holes in their guilt by innuendo arguments (e.g., there is nothing special in having 10k+ global variables in 1MLOC of source and the count should be by individual program not in total, and the nonsense claims around McCabe’s metric), and got an email from one of the experts in the case, who was not pleased.